doi: 10.56294/mw2023139

ORIGINAL

Exploring Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions and Practices on Telemedicine Adoption in Rural Regions

Exploración de las percepciones y prácticas de los profesionales sanitarios sobre la adopción de la telemedicina en las regiones rurales

Sumol Ratna1 ![]() *,

Komal Lochan Behera2

*,

Komal Lochan Behera2 ![]() , Renuka Jyothi R3

, Renuka Jyothi R3 ![]()

1Noida International University, Department of General Medicine. Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India.

2IMS and SUM Hospital, Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan (deemed to be University), Department of General Medicine. Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India.

3School of Sciences, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University), Department of Life Sciences. Karnataka, India.

Cite as: Ratna S, Behera KL, Renuka JR. Exploring Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions and Practices on Telemedicine Adoption in Rural Regions. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2023; 2:139. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw2023139

Submitted: 16-09-2022 Revised: 28-12-2022 Accepted: 01-03-2023 Published: 02-03-2023

Editor: PhD.

Prof. Estela Morales Peralta ![]()

Corresponding Author: Sumol Ratna *

ABSTRACT

In rural areas with limited access to medical facilities, telemedicine has become a transformative tool in healthcare delivery. However, issues including insufficient technology infrastructure, a lack of training, and patient privacy concerns are impeding the use of telemedicine in these regions. The purpose of the research is to investigate how medical professionals in these areas perceive and utilize telemedicine. A systematic survey was used to gather information from 300 medical professionals who worked in rural healthcare settings, including doctors, nurses, and technicians. The questionnaire evaluated perceived advantages, obstacles, and comfort levels as well as other aspects affecting the adoption of telemedicine. The IBM SPSS statistical version of 29 was utilized. There are three tests used in the statistical analysis: regression analysis to examine predictors of telemedicine acceptance, t-tests to compare differences in perceptions based on professional roles, and Chi-Square Test to determine whether there is an association between adoption status and rural vs. urban settings. The results showed that although medical experts acknowledged the possibility of telemedicine to increase patient outcomes and access to care, major obstacles were found, such as a lack of training, concerns about patient privacy, and inadequate technology infrastructure. Healthcare workers’ comfort levels with telemedicine vary, with doctors being more likely to use it. The research suggests that interventions like regulatory support, improved infrastructure, and training initiatives are needed to overcome obstacles using telemedicine. These measures are crucial for telemedicine to become a sustainable and integrated part of rural healthcare delivery.

Keywords: Rural Region; Telemedicine; Technology Infrastructure; Patient Privacy; Healthcare Professionals.

RESUMEN

En las zonas rurales con acceso limitado a centros médicos, la telemedicina se ha convertido en una herramienta transformadora de la prestación de asistencia sanitaria. Sin embargo, problemas como una infraestructura tecnológica insuficiente, la falta de formación y la preocupación por la privacidad de los pacientes obstaculizan el uso de la telemedicina en estas regiones. El objetivo de esta investigación es conocer cómo perciben y utilizan la telemedicina los profesionales médicos de estas zonas. Se utilizó una encuesta sistemática para recabar información de 300 profesionales médicos que trabajaban en entornos sanitarios rurales, entre ellos médicos, enfermeros y técnicos. El cuestionario evaluaba las ventajas, los obstáculos y los niveles de comodidad percibidos, así como otros aspectos que afectan a la adopción de la telemedicina. Se utilizó la versión estadística 29 de IBM SPSS. En el análisis estadístico se utilizaron tres pruebas: análisis de regresión para examinar los factores predictivos de la aceptación de la telemedicina, pruebas t para comparar las diferencias en las percepciones en función de las funciones profesionales, y la prueba Chi-cuadrado para determinar si existe una asociación entre el estado de adopción y los entornos rurales frente a los urbanos. Los resultados mostraron que, aunque los expertos médicos reconocían la posibilidad de la telemedicina para aumentar los resultados de los pacientes y el acceso a la atención, se encontraron importantes obstáculos, como la falta de formación, la preocupación por la privacidad de los pacientes y una infraestructura tecnológica inadecuada. Los niveles de comodidad del personal sanitario con la telemedicina varían, siendo los médicos los más propensos a utilizarla. La investigación sugiere que para superar los obstáculos que plantea el uso de la telemedicina son necesarias intervenciones como el apoyo normativo, la mejora de la infraestructura y las iniciativas de formación. Estas medidas son cruciales para que la telemedicina se convierta en una parte sostenible e integrada de la prestación sanitaria rural.

Palabras clave: Región Rural; Telemedicina; Infraestructura Tecnológica; Privacidad del Paciente; Profesionales Sanitarios.

INTRODUCTION

Telemedicine has become an innovative health technology that facilitates access to medical knowledge remotely and enhances outcomes for patients, especially in rural and underserved communities. Telemedicine uses digital communication technologies to allow healthcare practitioners to diagnose, manage, and monitor patients from a distance, thus filling gaps in care based on geography and availability of resources.(1) The procedure of healthcare provision is particularly critical in rural areas, where there is a shortage of medical professionals, poor healthcare facilities, and great distances to travel, which often deter the timely undertaking of quality healthcare services.(2) As much as telemedicine has great potential, its use within rural healthcare centers is patchy, with various factors determining its implementation and utilization.(3)

Among the major drivers of rural telemedicine, implementation is reducing disparities in healthcare through extending medical service coverage. Analysis have proved that telemedicine can improve emergency services, treatment for chronic conditions, mental health services, and specialist consultations without asking patients to cover long distances to access medical care.(4) Moreover, telemedicine offers the possibility of real-time consultation between rural physicians and specialists in urban areas, resulting in improved decision-making and patient outcomes. Nevertheless, despite these benefits, most rural healthcare facilities underutilize or altogether avoid telemedicine services, calling for concern regarding the determinants of adoption.(5)

Healthcare professionals have a critical part to play in the successful integration of telemedicine since their attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors play a crucial role in integrating telemedicine into practice.(6) Telemedicine adoption by these healthcare professionals depends on a host of factors that include technological preparedness, perceived ease of use, organizational readiness, payment plans, and patient acceptance.(7) While telemedicine is considered an asset by some providers to address rural health challenges, others identify shortcomings in terms of technology limitations, workflow disruption, training requirements, and economic sustainability of telemedicine programs. In addition, regulatory and policy challenges like licensure and insurance reimbursement hinder the application of telemedicine in rural areas.(8) Telemedicine adoption has centered on patient attitudes, technological infrastructure, and policy environments, with limited attention given to the attitudes and experiences of healthcare providers. It is critical to understand how rural healthcare providers perceive and integrate telemedicine into their practice in developing effective strategies to promote its adoption. Through the examination of their attitudes, challenges, and best practices, policymakers, healthcare managers, and technology designers can improve responses to barriers and facilitate broader telemedicine use in rural healthcare systems.

Focus groups with 17 participants were used in this investigation to determine how the community in rural Western North Carolina felt about a tele-COPD program.(9) Concerns about expense, privacy, uneasiness with technology, and low knowledge were among the obstacles, despite the high level of interest (94 %). In order to improve adoption, providers and pharmacists are essential. A constraint that limited further generalizability was the small, homogeneous sample. The use of telemedicine in public hospitals in rural notion was examined, which identifies seven major categories.(10) It used partial least squares structural equation modeling on data from 500 telemedicine patients to verify that trustworthiness, patient happiness, health staff motivation, and organizational performance were important obstacles. It identifies issues, makes policy recommendations, and makes recommendations for more analysis.

The use of telemedicine in cardiovascular care was examined by rural health professionals.(11) Through semi-structured interviews with 10 experts, it was discovered that developing telehealth requires stakeholder participation. Disparate expectations and technological problems were among the difficulties. One drawback was the small sample size, which limited the capacity to generalize more broadly. The perspectives of eHealth and telemedicine among present and prospective healthcare professionals, as well as whether student and worker opinions differ, were evaluated.(12) Students had a modest level of understanding of these technologies, according to a 905-individual online survey, while many were less certain of their advantages. Its limitations include the self-reported nature, thus restricted emphasis on a single university and its limited generalizability.

Using keyword exploration and qualitative analysis on HC3i.cn, it investigated how telemedicine and mHealth were perceived.(13) 571 threads' worth of data showed eight major themes that highlighted both potential and difficulties. Even though telemedicine has great promise, issues with cost and quality have surfaced. However, methodological constraints might impact generalizability, necessitating more evaluation to get a more profound understanding. To investigate how a setting of ambidexterity balances exploitative and exploratory learning to improve the adoption of telemedicine.(14) The findings from an analysis of survey data from 252 healthcare consumers used ADANCO 2.0.1, these learning processes influence the usage of technology. However, little was known about patient-centered frameworks, which emphasized the need for further investigation on the use of telemedicine in home healthcare settings.

The local government participants observed telemedicine due to the alleged lack of general practitioners.(15) Responses (N=605) to a survey that was distributed to 2199 German mayors were examined. Although misdiagnosis was a worry, the results indicated that 60 % of respondents had a positive view of telemedicine. Potential response bias and geographic emphasis were limitations that needed more extensive validation for generalizability. In the process of comparing the characteristics of telemedicine users and non-users, the investigation attempted to identify obstacles to telemedicine use in rural emergency departments (EDs).(16) Cost was identified as the main obstacle by experts who used another examination of the 2016 National Emergency Center Inventory survey. Its reliance on self-reported data, which might add bias, was a weakness.

The objective of this assessment is to examine the use and perceptions of telemedicine among rural health practitioners. It attempts to determine the benefits, limitations, and levels of comfort with the implementation of telemedicine, and factors that drive its adoption, including lack of training, concerns about patient privacy, and inadequate technology infrastructure as an approach to determining ways through which telemedicine can be optimized for incorporation in rural healthcare provision.

METHOD

Data were collected from 300 healthcare professionals (Doctors, nurses, and technicians) using a systematic survey-based assessment approach. A standardized questionnaire was employed to measure perception, barriers, and telemedicine use. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed research's basic concept.

Figure 1. Basic concept of proposed flow diagram

Participants

A total of 300 healthcare workers were recruited for this medical survey, including 110 doctors, 90 nurses, and 100 technicians. Doctors are more concerned with diagnosis and treatment, nurses with patients and coordination, and technicians with medical equipment and technology. Synthesizing participants' views allowed to identify facilitators and barriers to telemedicine implementation. Table 1 shows a structured breakdown of participant demographics, including gender, age, experience, and telemedicine experience. The majority of participants were male (55 %) and 31,7 % had between 1 to 5 years of experience in all professions. The largest age group was 31-40 years (35 %) and 50 % of participants had telemedicine experience.

|

Table 1. Demography data for all participants |

||||

|

Demographic Variables |

Doctors (n=110) |

Nurses (n=90) |

Technicians (n=100) |

Total (N=300) |

|

Gender |

||||

|

Male |

70 (63,6 %) |

35 (38,9 %) |

60 (60 %) |

165 (55 %) |

|

Female |

40 (36,4 %) |

55 (61,1 %) |

40 (40 %) |

135 (45 %) |

|

Age Group |

||||

|

20-30 years |

20 (18,2 %) |

25 (27,8 %) |

30 (30 %) |

75 (25 %) |

|

31-40 years |

40 (36,4 %) |

30 (33,3 %) |

35 (35 %) |

105 (35 %) |

|

41-50 years |

30 (27,3 %) |

20 (22,2 %) |

20 (20 %) |

70 (23,3 %) |

|

51+ years |

20 (18,2 %) |

15 (16,7 %) |

15 (15 %) |

50 (16,7 %) |

|

Years of Experience |

||||

|

1-5 years |

25 (22,7 %) |

30 (33,3 %) |

40 (40 %) |

95 (31,7 %) |

|

6-10 years |

35 (31,8 %) |

25 (27,8 %) |

30 (30 %) |

90 (30 %) |

|

11-15 years |

25 (22,7 %) |

20 (22,2 %) |

15 (15 %) |

60 (20 %) |

|

16+ years |

25 (22,7 %) |

15 (16,7 %) |

15 (15 %) |

55 (18,3 %) |

|

Previous Telemedicine Experience |

||||

|

Yes |

60 (54,5 %) |

40 (44,4 %) |

50 (50 %) |

150 (50 %) |

|

No |

50 (45,5 %) |

50 (55,6 %) |

50 (50 %) |

150 (50 %) |

Data collection

Developed a standardized questionnaire to collect data from 300 healthcare professionals, including doctors, nurses, and technicians. The questionnaire was designed to measure three key elements. These are the benefits of telemedicine as perceived by health workers, barriers to telemedicine adoption, and the comfort level of using telemedicine. The advantages of telemedicine, such as better patient access and results, were discussed by the respondents, along with drawbacks including a lack of technology, training, and privacy difficulties. The factors influencing the use of telemedicine in rural healthcare were examined using statistical inference. Table 2 shows a structured questionnaire designed to assess health employees' perceptions, barriers, and comfort levels with telemedicine implementation in rural areas. The questionnaire measures responses using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

|

Table 2. Healthcare Professionals' Perceptions, Barriers, and Comfort Levels Regarding Telemedicine Adoption in Rural Areas |

|

|

Category |

Question |

|

Perceived Advantages of Telemedicine |

Telemedicine improves access to healthcare for rural patients |

|

Telemedicine facilitates real-time consultation with specialists |

|

|

Telemedicine improves patient outcomes and continuity of care |

|

|

Barriers to Telemedicine Adoption |

Do you experience challenges related to limited technology infrastructure? |

|

Do you feel that there is a Lack of training and technical support for telemedicine use? |

|

|

Do you have any concerns regarding patient data privacy and security? |

|

|

Comfort Levels of Healthcare Professionals with Telemedicine |

Do you feel confident using telemedicine for patient consultations? |

|

Are you comfortable handling telemedicine-related technology and software? |

|

|

Do you believe you can effectively communicate with patients via telemedicine platforms? |

|

Data analysis

IBM SPSS Version 29 was used for statistical analysis. Regression analysis yielded predictors of telemedicine adoption. T-tests were used to compare healthcare workers' perceptions by professional category, for instance, doctors versus nurses. The chi-square test is whether there is a relationship between adoption status and rural and urban environments.

Performance evaluation

The health care professionals saw the promise of telemedicine to enhance patient outcomes and access to care but saw significant barriers to adoption, such as insufficient technology infrastructure, lack of training, and privacy concerns. The assessment using statistical strategies includes Regression analysis, T-test, and chi-square test.

Regression analysis

The assessment is a collection of statistical techniques used for estimating the correlations between several independent variables that are free of errors (wj) and a dependent variable. The majority of regression models suggest that Zj is the coefficient (regression function) wj and β, with fj denoting a cumulative term of error that could represent random statistical noise or un-modeled variables influencing Zj, as follows in equation (1):

![]()

To calculate the function e(wj, β) which most accurately matches the data.

|

Table 3. Regression Analysis of Factors Influencing Telemedicine Adoption among Rural Healthcare Professionals |

||||||

|

Participants |

Predictor Variable |

Coefficient (β) |

SE |

t-value |

p-value |

95 % CI (lower, upper) |

|

Doctor |

Constant (Intercept) |

2,1 |

0,45 |

4,67 |

0 |

(1,22, 2,98) |

|

Technological Infrastructure |

0,58 |

0,12 |

4,83 |

0 |

(0,34, 0,82) |

|

|

Lack of Training |

-0,45 |

0,15 |

-3 |

0,003 |

(-0,75, -0,15) |

|

|

Patient Privacy Concerns |

-0,38 |

0,14 |

-2,71 |

0,007 |

(-0,66, -0,10) |

|

|

Nurse |

Constant (Intercept) |

1,85 |

0,5 |

3,7 |

0 |

(0,87, 2,83) |

|

Technological Infrastructure |

0,49 |

0,14 |

3,5 |

0,001 |

(0,21, 0,77) |

|

|

Lack of Training |

-0,52 |

0,18 |

-2,89 |

0,004 |

(-0,88, -0,16) |

|

|

Patient Privacy Concerns |

-0,41 |

0,16 |

-2,56 |

0,011 |

(-0,72, -0,10) |

|

|

Technician |

Constant (Intercept) |

1,6 |

0,55 |

2,91 |

0,004 |

(0,52, 2,68) |

|

Technological Infrastructure |

0,42 |

0,16 |

2,63 |

0,009 |

(0,10, 0,74) |

|

|

Lack of Training |

-0,6 |

0,2 |

-3 |

0,003 |

(-1,00, -0,20) |

|

|

Patient Privacy Concerns |

-0,35 |

0,18 |

-1,94 |

0,053 |

(-0,71, 0,01) |

|

|

Note: Standard Error- SE, and Confidence Interval-CI |

||||||

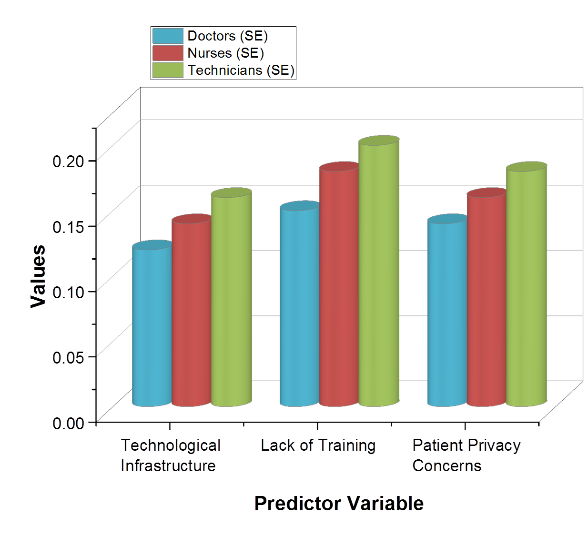

Figure 2. Standard Error Values for Predictors of Telemedicine Adoption in Healthcare Professionals

All healthcare professionals’ benefit from technology infrastructure involves telemedicine adoption but doctors are most affected (β = 0,58, p < 0,001) as determined by regression analysis as shown in table 3. On the contrary, adoption is significantly impeded by lack of training, especially for technicians. Concerns about patient privacy also affect adoption but with a weaker force relative to training constraints. Figure 2 illustrates the Standard Error Values for Predictors. Physicians, as a professional group, were most likely to employ telemedicine, and technicians were most likely to have barriers. Building up infrastructures and targeted training can improve telemedicine uptake in rural health settings.

Independent T-test

Examine two distinct groups' means for determining if there is evidence that the means of the connected groups differ significantly. A particular kind of statistical test is the Independent Samples t-test. The test statistic s is calculated in equations (2-3) as follows when it assumes that the two distinct samples originated from populations that had the same population differences:

![]()

![]()

w ̅1 is the initial sample mean. The mean of the second sample is w ̅2. m1 and m2 denoted the Initial sample size. m2 of the second sample size. The standard deviation of the first sample is a t1. The second sample's standard deviation is the t2, to is the aggregated standard deviation.

|

Table 4. Independent t-test Results Comparing Perceptions of Telemedicine Adoption among Healthcare Professionals |

||||||||

|

Variable |

Professional Role |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

t-value |

df |

p-value (Sig.) |

95 % CI of Difference |

|

Technological Infrastructure |

Doctor |

110 |

3,85 |

0,75 |

4,21 |

198 |

0,000** |

[0,32, 1,05] |

|

Nurse |

90 |

3,2 |

0,82 |

|||||

|

Lack of Training |

Doctor |

110 |

4,12 |

0,68 |

3,89 |

198 |

0,001** |

[0,22, 0,94] |

|

Nurse |

90 |

3,5 |

0,74 |

|||||

|

Patient Privacy Concerns |

Doctor |

110 |

3,9 |

0,7 |

2,78 |

198 |

0,006** |

[0,15, 0,88] |

|

Nurse |

90 |

3,45 |

0,79 |

|||||

|

Technological Infrastructure |

Doctor |

110 |

3,85 |

0,75 |

5,1 |

208 |

0,000** |

[0,50, 1,20] |

|

Technician |

100 |

3,1 |

0,88 |

|||||

|

Lack of Training |

Doctor |

110 |

4,12 |

0,68 |

4,05 |

208 |

0,000** |

[0,30, 1,10] |

|

Technician |

100 |

3,4 |

0,8 |

|||||

|

Patient Privacy Concerns |

Doctor |

110 |

3,9 |

0,7 |

2,95 |

208 |

0,004** |

[0,20, 0,85] |

|

Technician |

100 |

3,5 |

0,82 |

|||||

|

Technological Infrastructure |

Nurse |

90 |

3,2 |

0,82 |

2,85 |

188 |

0,005** |

[0,10, 0,75] |

|

Technician |

100 |

3,1 |

0,88 |

|||||

|

Lack of Training |

Nurse |

90 |

3,5 |

0,74 |

2,62 |

188 |

0,009** |

[0,08, 0,65] |

|

Technician |

100 |

3,4 |

0,8 |

|||||

|

Patient Privacy Concerns |

Nurse |

90 |

3,45 |

0,79 |

2,1 |

188 |

0,037* |

[0,02, 0,65] |

|

Technician |

100 |

3,5 |

0,82 |

|||||

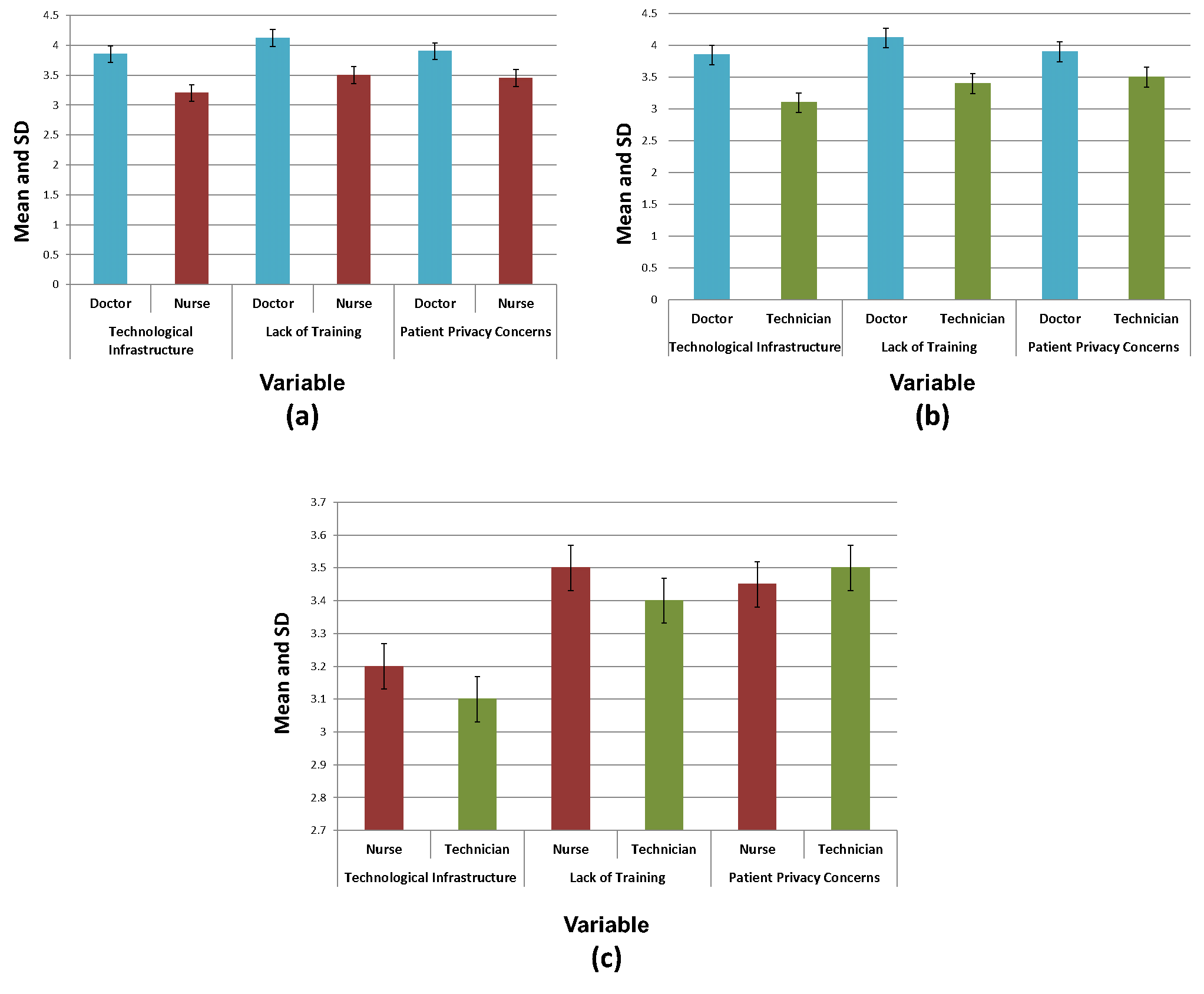

Figure 3. Mean and SD calculation for perceptions of telemedicine across (a) Doctor vs. Nurse, (b) Doctor vs. Technician and (c) Nurse vs. Technicians

The independent t-test results indicate significant differences in perceptions of telemedicine among doctors, nurses, and technicians as shown in table 4 and figure 3 illustrate the Mean and SD calculation for perceptions of telemedicine across (a) Doctor vs. Nurse, (b) Doctor vs. Technician and (c) Nurse vs. Technicians. Doctors rated technological infrastructure and lack of training more constructively than nurses (p = 0,000, p = 0,001) and technicians (p = 0,000, p = 0,000), showing higher acceptance of telemedicine. Privacy concerns were lower among doctors than among nurses (p = 0,006) and technicians (p = 0,004). Nurses and technicians were equally concerned, but nurses were slightly more concerned about better infrastructure (p = 0,005) and lack of training (p = 0,009). These results highlight the importance of role-based training and infrastructure development to ensure the implementation success of telemedicine.

Chi-Square test

An approach used in statistics to ascertain how actual and predicted data differ is the Chi-Square test. Finding out if it corresponds with the categorical variables in our data is a different objective for this test. Determining whether a difference between two categorical variables exists because of chance or because of an association between them is essential.

![]()

Where equation (4) denoted the Degrees of freedom as (d), (O) as Value Observed, E stands for expected value.

|

Table 5. Outcomes of chi-Square test of Adoption Status |

||||||||||

|

Adoption Status |

Rural |

Urban |

Chi-Square (χ²) |

df |

sig.(α) |

Chi-Square Critical Value |

||||

|

O |

E |

(O - E)² / E |

O |

E |

(O - E)² / E |

12,5 |

1 |

0,05 |

3,84 |

|

|

Adopters |

75 |

90 |

2,5 |

105 |

90 |

2,5 |

||||

|

Non-Adopters |

75 |

60 |

3,75 |

45 |

60 |

3,75 |

||||

|

Total |

150 |

150 |

6,25 |

150 |

150 |

6,25 |

||||

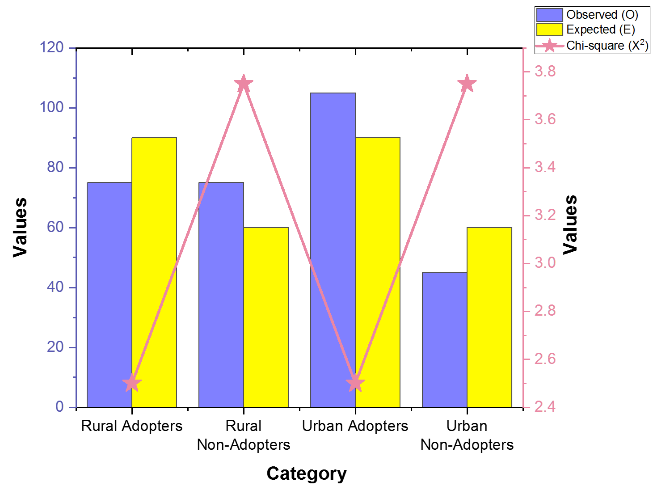

Figure 4. Chi-Square Test Observed vs. Expected Frequencies

The statistical test was used to investigate the connection amongst the use of telemedicine and healthcare environment (urban and rural) as shown in table 5. Figure 4 illustrates the Chi-Square Test Observed vs. Expected Frequencies. As it is computed χ² = 12,5 and the critical value for 3,84 at α = 0,05, which implies that urban healthcare providers use telemedicine more than rural healthcare providers. Infrastructure, training, and policy support could be the reasons for the difference. Identifying these differences can be used to create targeted solutions to enhance telemedicine uptake in rural communities, providing improved access and efficiency in healthcare.

DISCUSSION

The attitudes andpractices of healthcare providers towards the adoption of telemedicine in rural regions is examined. It identifies major obstacles like technology insufficiency, training deficiency, and privacy issues while promoting regulation assistance, infrastructure creation, and training programs to ensure the adoption of telemedicine. Regression analysis revealed that technological infrastructure significantly facilitated the adoption of telemedicine, with doctors being the most affected group (β = 0,58, p < 0,001). However, lack of training was the biggest barrier, especially for technicians. Concerns about patient privacy were also a barrier to adoption, although to a lesser extent. The independent t-test showed that doctors were more accepting of telemedicine than nurses and technicians, rating technological infrastructure and training needs more positively (p < 0,001). Nurses and technicians had similar privacy concerns, though nurses emphasized the need for better infrastructure (p = 0,005). The final also established an important association among telemedicine adoption and the healthcare environment (χ² = 12,5, p < 0,05), as telemedicine was adopted more in urban healthcare facilities compared to rural healthcare facilities. This variation is likely due to variations in infrastructure, training, and policy support. The results indicate the necessity for targeted interventions, such as infrastructure development, specialized training, and policy reforms, to facilitate increased telemedicine adoption in rural healthcare facilities. Restricted by its use of a healthcare sample size that is small, which might not represent the whole area. It also relied on self-report measures, potentially introducing bias. Subsequent exploration must include a wider, mixed sample and analyze longitudinal impacts of telemedicine adoption, focusing on real-world effects and sustainability within rural environments.

CONCLUSIONS

The aim of the research is to determine the healthcare professional’s perceptions and usage of telemedicine and their barriers and enablers towards uptake. There was a systematic survey of 300 medical professionals comprising 110 doctors, 90 nurses, and 100 technicians. Questionnaire-assessed perceived advance, barriers, and telemedicine comfort level. Statistical testing was carried out using the help of IBM SPSS version 29 software through regression analysis, t-tests, and the Chi-Square test to test for variable association. The findings revealed that while telemedicine was well recognized to enhance patient outcomes, several barriers emerged between its adoption. Technological infrastructure was shown to have a great influence on doctors' adoption via regression analysis (β = 0,58, p < 0,001), while insufficient training was a major obstacle for technicians. Independent t-test revealed that telemedicine was more acceptable to physicians than to nurses and technicians, where differences were statistically significant (p < 0,001). The χ² = 12,5, p < 0,05 also revealed that telemedicine adoption was higher in urban areas than in rural areas. These findings highlighted the necessity for better infrastructure, specific training programs, and regulatory assistance to facilitate telemedicine deployment in rural healthcare environments.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Barbosa W, Zhou K, Waddell E, Myers T, Dorsey ER. Improving access to care: telemedicine across medical domains. Annual review of public health. 2021 Apr 1; 42(1):463-81. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090519-093711

2. Abelsen B, Strasser R, Heaney D, Berggren P, Sigurðsson S, Brandstorp H, Wakegijig J, Forsling N, Moody-Corbett P, Akearok GH, Mason A. Plan, recruit, retain: a framework for local healthcare organizations to achieve a stable remote rural workforce. Human resources for health. 2020 Dec; 18:1-0. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00502-x

3. Zobair KM, Sanzogni L, Houghton L, Sandhu K, Islam MJ. Health seekers’ acceptance and adoption determinants of telemedicine in emerging economies. Australasian Journal of Information Systems. 2021. https://dx.doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v25i0.3071

4. Hirko KA, Kerver JM, Ford S, Szafranski C, Beckett J, Kitchen C, Wendling AL. Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for rural health disparities. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2020 Nov; 27(11):1816-8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa156

5. Morenz AM, Wescott S, Mostaghimi A, Sequist TD, Tobey M. Evaluation of barriers to telehealth programs and dermatological care for American Indian individuals in rural communities. JAMA dermatology. 2019 Aug 1; 155(8):899-905. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0872

6. Schinasi DA, Foster CC, Bohling MK, Barrera L, Macy ML. Attitudes and perceptions of telemedicine in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of naïve healthcare providers. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2021 Apr 7; 9:647937. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.647937

7. Ranganathan C, Balaji S. Key factors affecting the adoption of telemedicine by ambulatory clinics: insights from a statewide survey. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2020 Feb 1; 26(2):218-25. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0114

8. Schofield M. Regulatory and legislative issues on telehealth. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2021 Aug; 36(4):729-38. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncp.10740

9. Alexander DS, Kiser S, North S, Roberts CA, Carpenter DM. Exploring community members’ perceptions to adopt a Tele-COPD program in rural counties. Exploratory Research in Clinical and Social Pharmacy. 2021 Jun 1; 2:100023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsop.2021.100023

10. Zobair KM, Sanzogni L, Sandhu K. Telemedicine healthcare service adoption barriers in rural Bangladesh. Australasian Journal of Information Systems. 2020; 24. https://dx.doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v24i0.2165

11. Kocanda L, Fisher K, Brown LJ, May J, Rollo ME, Collins CE, Boyle A, Schumacher TL. Informing telehealth service delivery for cardiovascular disease management: exploring the perceptions of rural health professionals. Australian Health Review. 2021 Mar 15; 45(2):241-6. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH19231

12. Wernhart A, Gahbauer S, Haluza D. eHealth and telemedicine: Practices and beliefs among healthcare professionals and medical students at a medical university. PloS one. 2019 Feb 28; 14(2):e0213067. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213067

13. Leung R, Guo H, Pan X. Social media users’ perception of telemedicine and mHealth in China: exploratory study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2018 Sep 25;6(9):e7623. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.7623

14. Cegarra-Sánchez J, Cegarra-Navarro JG, Chinnaswamy AK, Wensley A. Exploitation and exploration of knowledge: An ambidextrous context for the successful adoption of telemedicine technologies. Technological forecasting and social change. 2020 Aug 1; 157:120089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120089

15. Weißenfeld MM, Goetz K, Steinhäuser J. Facilitators and barriers for the implementation of telemedicine from a local government point of view-a cross-sectional survey in Germany. BMC Health Services Research. 2021 Dec; 21:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06929-9

16. Zachrison KS, Boggs KM, Hayden EM, Espinola JA, Camargo Jr CA. Understanding barriers to telemedicine implementation in rural emergency departments. Annals of emergency medicine. 2020 Mar 1; 75(3):392-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.06.026

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Sumol Ratna, Komal Lochan Behera, Renuka Jyothi R.

Data curation: Sumol Ratna, Komal Lochan Behera, Renuka Jyothi R.

Formal analysis: Sumol Ratna, Komal Lochan Behera, Renuka Jyothi R.

Drafting - original draft: Sumol Ratna, Komal Lochan Behera, Renuka Jyothi R.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Sumol Ratna, Komal Lochan Behera, Renuka Jyothi R.