doi: 10.56294/mw2024474

REVIEW

HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men: Challenges and Strategies

Factores de Prevención del VIH en Hombres que tienen Sexo con Hombres: Desafíos y Estrategias

Juan Carlos Plascencia-De la Torre1 ![]() *, Kalina Isela Martínez-Martínez2

*, Kalina Isela Martínez-Martínez2 ![]() , Fredi Everardo Correa-Romero3

, Fredi Everardo Correa-Romero3 ![]() , Ricardo Sánchez-Medina4

, Ricardo Sánchez-Medina4 ![]() , Oscar Ulises Reynoso-González1

, Oscar Ulises Reynoso-González1 ![]() *

*

1Universidad de Guadalajara. Guadalajara, México.

2Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, Departamento de psicología. Aguas calientes, México.

3Universidad de Guanajuato. México.

4Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México.

Cite as: Plascencia-De la Torre JC, Martínez-Martínez KI, Correa-Romero FE, Sánchez-Medina R, Reynoso-González OU. HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men: Challenges and Strategies. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2024; 3:474. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw2024474

Submitted: 28-09-2023 Revised: 18-02-2024 Accepted: 05-05-2024 Published: 06-05-2024

Editor: PhD.

Prof. Estela Morales Peralta ![]()

Corresponding Author: Juan Carlos Plascencia-De la Torre *

ABSTRACT

Introduction: human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) has represented a serious public health problem worldwide. Despite advances in its prevention and treatment, it continues to affect millions of people, especially key populations, such as Men who have Sex with Men (MSM). In Mexico, MSM have presented a significantly higher risk of infection compared to other population groups. This phenomenon has been attributed to biological, psychological, social and structural factors that increase the vulnerability of this population.

Development: condoms have been identified as an effective tool in HIV prevention, as they significantly reduce the risk of transmission. However, its use has faced several barriers, including behavioral aspects, lack of access to quality condoms and social norms that discourage its use. In addition, HIV has evolved since its discovery in the 1980s, presenting different stages of development, means of transmission and diagnostic strategies. Antiretroviral treatment has managed to improve the quality of life of people with HIV, although its effectiveness has been influenced by multiple factors. Several theoretical models have attempted to explain HIV risk behavior and prevention, allowing a comprehensive approach to address the problem in MSM.

Conclusions: HIV prevention in MSM has required the implementation of strategies that address biological, psychological and social factors. It is crucial to strengthen sex education, improve access to condoms and reduce discrimination affecting this population.

Keywords: HIV; Prevention; Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM); Condoms; Public Health.

RESUMEN

Introducción: el Virus de Inmunodeficiencia Humana (VIH) ha representado un grave problema de salud pública a nivel mundial. A pesar de los avances en su prevención y tratamiento, sigue afectando a millones de personas, especialmente a poblaciones clave, como los Hombres que tienen Sexo con Hombres (HSH). En México, los HSH han presentado un riesgo significativamente mayor de infección en comparación con otros grupos poblacionales. Este fenómeno se ha atribuido a factores biológicos, psicológicos, sociales y estructurales que aumentan la vulnerabilidad de esta población.

Desarrollo: el condón ha sido identificado como una herramienta efectiva en la prevención del VIH, ya que reduce significativamente el riesgo de transmisión. No obstante, su uso ha enfrentado diversas barreras, incluyendo aspectos conductuales, la falta de acceso a condones de calidad y normas sociales que desalientan su uso. Además, el VIH ha mostrado una evolución desde su descubrimiento en los años 80, presentando distintas etapas de desarrollo, medios de transmisión y estrategias de diagnóstico. El tratamiento antirretroviral ha logrado mejorar la calidad de vida de las personas con VIH, aunque su efectividad se ha visto influenciada por múltiples factores. Diversos modelos teóricos han intentado explicar la conducta de riesgo y prevención del VIH, permitiendo un enfoque integral para abordar la problemática en los HSH.

Conclusiones: a prevención del VIH en los HSH ha requerido la implementación de estrategias que aborden los factores biológicos, psicológicos y sociales. Es crucial fortalecer la educación sexual, mejorar el acceso a preservativos y reducir la discriminación que afecta a esta población.

Palabras clave: VIH; Prevención; Hombres que Tienen Sexo con Hombres (HSH); Condón; Salud Pública.

INTRODUCCIÓN

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) continues to be a significant public health problem worldwide. Despite advances in prevention and treatment, HIV continues to affect millions of people, making it one of the leading causes of morbidity in the world. Key populations, which include men who have sex with men (MSM), continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV. In Mexico, MSM are 28 times more at risk of infection compared to other key populations and 44 times more at risk compared to the general population (CENSIDA, 2021). This is due to a combination of biological, psychological, social, and structural factors that increase the vulnerability of this population to HIV (Tobón & García, 2022). Addressing these factors and providing culturally appropriate prevention and treatment services are critical steps in reducing the incidence of HIV in this key population.

The condom has been recognized for decades as a fundamental preventive measure in the fight against HIV transmission. Its effectiveness in reducing the risk of acquiring the virus has been widely demonstrated, and it is a crucial tool in HIV prevention among MSM (Stover & Teng, 2022). Despite its effectiveness, condom use is hampered by a series of cognitive-behavioral barriers, lack of access to quality condoms, and the influence of cultural and social norms that discourage their use (Gredig et al., 2020; Hentges et al., 2023; Morell et al., 2021). It is crucial to address these barriers comprehensively to promote consistent condom use among MSM.

DEVELOPMENT

General information on HIV/AIDS

Origin and conceptualization of HIV and AIDS

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an infection that is commonly transmitted sexually (Posada et al., 2020). When HIV is not treated in time, it begins to eliminate blood cells called lymphocytes progressively, specifically the CD4 receptor (LTCD4+); lymphocytes protect and defend the immune system from other foreign agents so that when HIV attacks and eliminates defense cells, the person's immune system is vulnerable to attack by other infectious microorganisms (Rojas, 2021; Valencia & Trujillo, 2021).

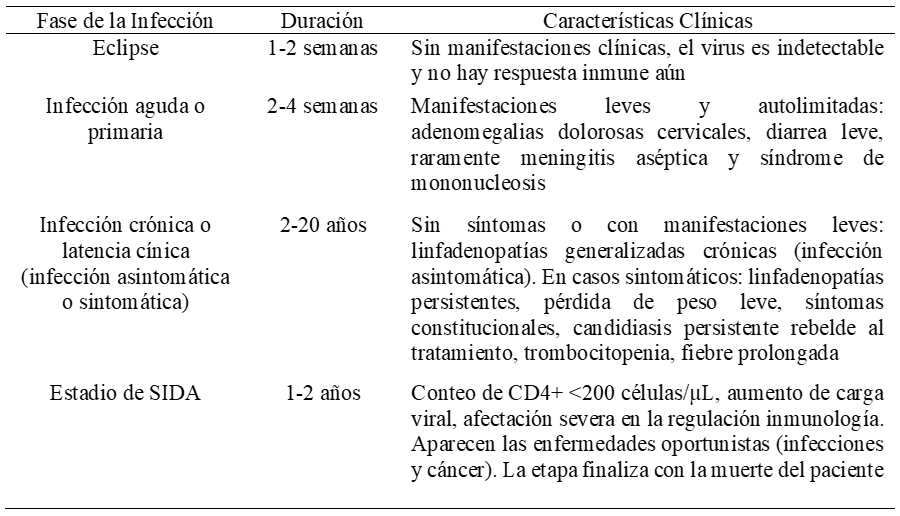

When the patient acquires HIV, the natural course of the infection begins, characterized by four stages: eclipse, acute or primary infection, chronic infection, and AIDS stage (figure 1).

Source: Chávez and Castillo (2013), Boza (2017), Del Amo et al. (2017), Prabhu et al. (2019).

Figure 1. Stages and clinical characteristics of HIV

If the viral load is not controlled and the virus continues to replicate, it evolves into what we know as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). This stage is defined as the advanced stage of HIV, where the individual presents a significant decrease in their ability to defend against infections due to the decrease in the levels of their lymphocyte count. The syndrome itself does not generate the main symptoms of AIDS. However, they are derived from complications associated with opportunistic infections such as respiratory and gastrointestinal problems, significant weight loss, and, in critical cases, oncological diseases such as Kaposi's sarcoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (Boza, 2017).

In general, the terms HIV and AIDS are used interchangeably, which leads to a conceptual error, as people living with HIV can develop clinical symptoms ranging from the asymptomatic period at diagnosis to the terminal or advanced stage of the syndrome (Prabhu et al., 2019; Sharp & Hahn, 2010; Valencia & Trujillo, 2021); in this sense, HIV and AIDS are different stages with different symptoms that can lead to prejudice and stigma from society.

HIV originated in the early 1980s when the United States of America reported its first five cases of atypical pneumonia in sexually active men assumed to be homosexual. Months later, several cases of Kaposi's sarcoma and other diseases of the immune system were detected in relatively healthy men who led an active sex life with other men (Boza, 2016; González, 2014). From the outset, the issue of detecting the first cases of homosexual men attracted attention, as they were a historically and socially marginalized group, which, from the early years of the epidemic, some conservative and religious groups already described as an aberration and divine punishment.

In Mexico, the first cases were identified in 1983 by the National Institute of Nutrition (INN) and the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), which received the first patients who had been hospitalized with advanced pneumonia; by September of that year, 14 cases had already been recorded (Ponce de León, 2011).

Development of HIV

Means of transmission

HIV is transmitted in various ways (parenteral and perinatal), but commonly through sexual transmission (Posada et al., 2020). According to the epidemiological report of the Secretary of Health in Mexico (2023), of the total accumulated cases (from 1983 to 2026), 96,2 % of them acquired the virus through sexual transmission (anal-vaginal or oral), 1,4 % through vertical transmission (mother-to-child), 1,2 % through syringes in injecting drug users, and 0,8 % through blood transfusions; however, during the year 2023, 99,6 % of cases acquired HIV through sexual transmission.

Diagnosis

For HIV detection, a blood test called the Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA) is used, which detects the presence of antibodies in the person. This test can yield a false "negative" result, meaning no detectable antibodies were found in the person. The reason for this is derived from the immune system's response to a virus, which can take up to three months to be detected. This is called the "immunological window period," in which the person may test negative for the presence of antibodies but have CD4+ T cells already infected with the virus. Therefore, if it is known that there is a risk of contagion, it is advisable to repeat the test 3 to 4 months after the possible infection (Del Amo et al., 2017).

On the other hand, there is also the possibility of a false "positive" result using ELISA, which means that antibodies against HIV have been detected in the person's body. A second ELISA test is used to confirm the specificity of the result, and if, on this second occasion, the result is again positive, a final confirmatory test called Western Blot must be applied. This is a more specific and complete test for the detection of antibodies against different HIV antigens, which, when it yields a negative result, means that there was a cross-reaction with some other non-specific antibody present in the patient and the patient can be diagnosed as uninfected; on the other hand, if the Western Blot yields a positive result, it means that the antibodies found are from HIV and the infection of this virus is confirmed. When the person's positive HIV status is confirmed, they receive drug treatment called antiretroviral therapy (Del Amo et al., 2017).

Treatment

An important advance in the control of HIV infection has been the development of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which aims to reduce the viral load (VL) to undetectable levels and improve the body's immune response, promoting an increase in the number of CD4+ T cells for as long as possible. Antiretroviral treatment should be started once it has been determined that the virus exists in the individual's body, and once the person is committed and agrees to undergo the treatment; this commitment will ensure better adherence to medical instructions and the taking of medication for an extended period (CENSIDA, 2021). Similarly, good adherence to initial treatment is essential in the development of the disease, as it optimizes the quality of life of the person with HIV and delays the progression of the infection to evolutionary stages such as AIDS (Almanza et al., 2018).

Despite the existence, availability, and effectiveness of antiretroviral treatments, it is estimated that a high percentage of patients under treatment fail to suppress their viral load and increase their CD4+ T cells. The effectiveness of antiretrovirals does not only depend on adequate therapeutic adherence but also on multiple factors such as genetic, viral, psychological, and social (Dos Santos et al., 2012; Herrera et al., 2014; Krummenacher et al., 2014; Plascencia-De la Torre et al., 2019).

Epidemiology

During the early years of the HIV-AIDS epidemic, the number of patients identified with this condition grew steadily. According to the latest UNAIDS reports (2023), at the end of 2022, it was reported that 39,0 million people were living with HIV worldwide (37,5 million were adults and 1,2 million were children), leaving a mortality rate of 630 000 people, added to the 40,4 million deaths since the beginning of the epidemic. In 2022, 1,3 million new HIV infections were recorded, which represents double the number of infections detected in 1997, with a reduction of 54 %. Since the peak in mortality in 2004, AIDS-related deaths have decreased by more than 68 %. In the same vein, UNAIDS reported that, at the end of 2022, 29,8 million people had access to antiretroviral treatment, compared to 7,8 million people in 2010.

According to the latest epidemiological report from the Ministry of Health (2023), in Mexico, 369 626 cases of HIV infection have been diagnosed from 1983 to January 2024, of which 302 975 (81,97 %) cases have been men and 66 651 (18,03 %) have been women. The age group with the most infections is between 20 and 39. The transmission category was sexual with 96,6 % of cumulative cases; in 2023, 16 941 new cases of HIV were registered, of which 99,6 % were sexually acquired. On the other hand, in the state of Jalisco, 1139 cases of HIV were reported during 2023, of which 1017 were men (89,3 %) and 122 women (10,7 %).

UNAIDS (2022) has identified that 65 % of new HIV infections worldwide have occurred more frequently in key populations, a concept used to refer to groups of people at higher risk of acquiring HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, including young people aged 15 to 24, injecting drug users, sex workers, people deprived of their freedom, transgender people, as well as men who have sex with men (MSM) regardless of their sexual orientation.

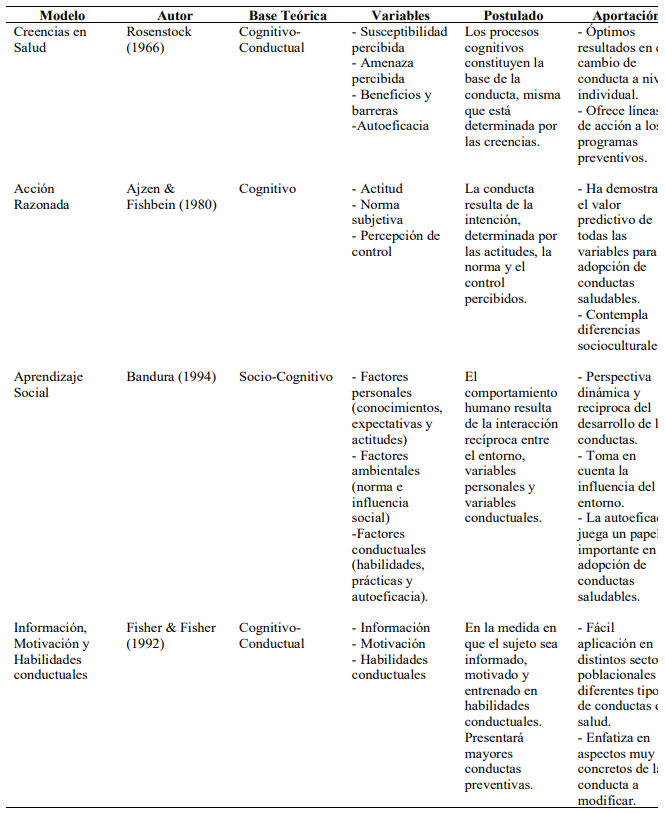

Theoretical models related to HIV

The emerging field of Health Psychology deals with issues related to the health-disease process, such as HIV, and its implications on a physical, psychological, family, work, and social level. According to Oblitas (2017), the Health Psychology professional must cover various functions, including conducting research into the factors associated with protective and risk behaviors for HIV acquisition. Although various models have been developed, those with the most scientific evidence will be mentioned below.

The Health Belief Model by Rosenstock (1966), adapted by Becker and Maiman (1975), has become one of the most widely used frameworks for understanding and explaining the process of various protective and risk behaviors for HIV. It is based on the premise that risk behaviors result from the internal beliefs and values a person brings to a given situation (Oblitas, 2017). Similarly, it considers other elements, such as the subject's susceptibility and perceived severity of the disease, the threat, and the perceived benefits of any preventive behavior, such as the correct use of condoms.

In other words, the model proposes that an individual's set of beliefs causes a certain degree of behavioral preparedness that will allow him or her to take action responsibly when facing an emerging problem. Taking the issue of HIV prevention as an example, for a subject to adopt safe sexual behaviors in order to prevent HIV infection, they must be aware of the seriousness of the disease, and this requires that they receive the necessary information and that they can see themselves as vulnerable if they do not engage in preventive behaviors such as condom use.

However, according to Oblitas (2017), taking into account the structure of the model, it is important to consider certain moderating factors that could indirectly affect health behaviors through the influence of health beliefs. These factors could be age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, religious beliefs, and personality, among other sociodemographic and psychological determinants.

Secondly, the Reasoned Action Model, developed by Ajzen and Fishbein, is presented, highlighting the importance of cognitive factors and motivation as key elements in determining health behavior in general. This model is based on the premise that human beings make rational decisions based on available information; that is, a person's behavior can be predicted by intention. That intention is determined by the person's attitude and subjective norm about healthy behavior.

In this sense, attitude refers to a person's positive or negative feelings toward healthy behavior. In contrast, subjective norm refers to the individual's perception of what the people around them think about that healthy behavior. This scheme applies to the process of adopting HIV preventive behaviors in adolescents and young people. For this, the individual must positively evaluate the possibility of using a condom during sexual relations and have favorable expectations regarding the benefits of its use; similarly, they must consider the positive expectations, interpretations, and meanings of their peers regarding preventive behavior that is, that if others use it, it is very likely that the individual will use a condom in their sexual practices (Espada et al., 2017).

On the other hand, Albert Bandura's Social Cognitive Model has been developed, which is based on the premise that human motivation and behavior are regulated by thought involving three elements that interact with each other:

1. Personal determinants such as cognitive, affective, and biological factors.

2. Behavior.

3. The environment (Bandura, 1999; 2005).

Within the socio-cognitive model, the concept of self-efficacy is developed, which, according to Bandura (1994), is people's beliefs about their ability to produce specific levels of performance that influence events in their lives. In simple terms, self-efficacy is a person's belief in their ability to engage in healthy behavior that leads to positive outcomes successfully. According to Bandura, to develop self-efficacy, it is necessary to teach self-regulation skills that allow individuals to control both their behaviors and external situations. These skills are related to managing motivation, beliefs, and actions.

Finally, for some years now, there has been a tendency to integrate different models of health behaviors using more precise variables that have been integrated into previous models. Within this integrative perspective, the Fisher and Fisher created the information Motivation and Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model (1992) to explain HIV/AIDS risk behaviors and prevention. Fisher and Fisher (1992) argue that three key components are required to achieve HIV prevention:

· Fundamental knowledge about HIV-AIDS, its methods of transmission, the symptoms and secondary risks in case of contracting it, as well as specific preventive behaviors.

· The motivation to adopt preventive behaviors is influenced by attitudes towards preventive actions, social norms related to prevention, and the perception of the risk of contracting HIV.

· The behavioral skills necessary to implement preventive behaviors, including the objective competencies that people have about preventive actions, such as the perception of self-efficacy to carry out these behaviors.

This model has been used to study HIV risk behaviors in diverse populations such as men and women of productive age, MSM, and people who are HIV positive and on antiretroviral treatment (Fisher, 2011; Fisher et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2019; Pérez, 2021; Santillán, 2014).

This model has been used to study HIV risk behaviors in diverse populations such as men and women of productive age, MSM, and people with an HIV-positive diagnosis and who are on antiretroviral treatment (Fisher, 2011; Fisher et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2019; Pérez, 2021; Santillán, 2014).

In conclusion, and as shown in figure 2, these models have been created sequentially and address prevention from different perspectives, each with a higher level of inclusion than the previous one. On occasion, they are used in an eclectic way to respond to the specific needs of key populations at risk of contracting HIV. However, these models do not fully consider other psychological variables that could explain risky sexual behavior, which is why it is essential to develop new studies that integrate other factors, both protective and risk factors.

Source: Antón Ruiz (2013)

Figure 2. Summary of theoretical models applied to HIV

MSM: key population for HIV infection risk

One of the key populations most affected by HIV in Latin American countries is MSM (men who have sex with men), a term coined by some epidemiologists to refer to all men who engage in romantic, sentimental and/or sexual relationships with other men, regardless of their sexual identity and orientation [homosexual, bisexual or heterosexual] (Acosta, 2021; Agüero et al., 2019), a situation that contributes significantly to the accelerated increase in favorable cases, a reality that becomes more complex as each reported case is multiplied by others who have not yet been diagnosed (Posada et al., 2020).

On many occasions, the MSM population is continually at risk due to the lack of community support and their social isolation; it is common for their relationships to be kept discreet and secret. Furthermore, the fear of being rejected by their loved ones, of losing their jobs, and of facing public criticism is a constant concern for those who seek to explore their sexuality with people of the same sex. According to Morosini (2011), it is estimated that in Latin American countries, the frequency of sexual relations between men varies considerably in adult populations according to geographical location, ranging from 1 in 500 to 1 in 45. Despite the breadth of this range, it provides relevant information that guides the planning of strategies and allocation of resources aimed at promoting healthy behaviors, self-care, and prevention measures against HIV transmission in the MSM population.

Despite the efforts made in the field of HIV prevention, MSM is reported to be 28 times more at risk of infection compared to other key populations and 44 times more at risk compared to the general population (CENSIDA, 2021). In a survey carried out in MSM meeting places in various regions of Mexico, an HIV prevalence of 16,9 % was detected, with prevalences higher than 19 % in areas of the center and south of the country (Bautista et al., 2013). According to Moral de la Rubia et al. (2016), this could be due to various social conditions, such as criticism, rejection by society and the family, and the need to carry out sexual encounters in secret. In this sense, it is crucial to bear in mind that the behavior of MSM is not distributed homogeneously in the male population. According to Morosini (2011), this is due to two main reasons:

a) Different sexual orientations and gender self-definitions can be identified that influence behavior and risk perception in different ways. These differences can have a significant impact on the way individuals approach their sexual health and the prevention of infections such as HIV.

b) Different geographical regions may exhibit cultural patterns in which intolerance and discrimination influence the mobility of the MSM population. This can lead to some individuals moving or being forced to hide their identity due to a less tolerant environment, affecting their access to health services and their ability to carry out prevention practices.

In that order, diversity in sexual orientation and cultural and geographical influences can have a significant impact on the behavior and perception of risk of the MSM population, which underlines the importance of addressing these differences in health promotion and HIV prevention.

Several studies have shown that specific biological determinants could be associated with the risk of HIV infection in the MSM population compared to the general population (Cantu et al., 2022; Jose et al., 2020; Martinez et al., 2017). In this sense, the biological dimension represents a significant element in MSM, leaving them in a state of susceptibility, such is the case of the presence of other STIs, which can increase the risk of contracting the virus, that is to say, STIs reduce immune protection against other infections, leaving the person vulnerable to contracting HIV (Collins & Walker, 2016). In a study of 9,113 MSM, the factors affecting HIV incidence in men after being diagnosed with syphilis were examined, revealing that 8 % of the participants had contracted HIV in follow-ups after the study, with an average time of detection of 1,9 years following the diagnosis of syphilis (Cantu et al., 2022). These findings confirm the idea that the presence of other STIs can determine the risk of acquiring HIV.

Another risk factor in MSM is unprotected anal intercourse, with a higher probability of transmission in the receptive person than for the man performing the penetration because the anus is covered by a single layer of mucosa, which is very thin and tears easily on contact with the penis, which is why microbleeds can occur, enabling blood-mucosa contact, how the virus is transmitted (Collins & Walker, 2016). An example of this was the study by Kritsanavarin et al. (2020) who carried out a six- and eight-month prospective cohort study in 1,411 MSM and transgender women to measure the incidence of HIV and evaluate the factors associated with incident infections; among the results, they found an HIV incidence of 3,5 % and a direct association with having receptive anal sex in the last six months, which leads to its identification as a risk factor from a biological and psychological perspective.

Another factor to take into account is men's beliefs about condom use, seeing it as an impediment to enjoying pleasure during sexual intercourse. These beliefs reflect the model of masculinity that prevails in society and which, linked to a conception of physical pleasure, requires men to assume an active role in sexual activity (Uribe et al., 2017).

It is important to clarify that anal penetration is not exclusive to MSM. To a certain extent, they share some psychosocial determinants of the heterosexual population, so it is important to consider the specific factors of this key population (Posada et al., 2020). Estrada (2014) considers that prevention campaigns tend to overlook the complexity of MSM motivations and the emotional meanings assigned to them. Safer sex or condom use can be seen as offensive and generate complex interpretations. In contrast, unprotected sex is seen as facilitating greater closeness and intimacy with a stable partner and is assumed to be a usual risk-free practice. In this sense, risky sexual practices among men constitute a global public health problem, to a certain extent associated with psychosocial factors, among which the low perception of risk towards the disease, low self-esteem, clandestine sexual experiences facilitated by the consumption of psychoactive substances, the number of sexual partners and the inconsistent use of condoms stand out (Betancourt et al., 2021; Jose et al., 2020; Kritsanavarin et al., 2020; McKenney et al., 2020).

Therefore, it is essential to move forward with new studies that analyze how cognitive and behavioral determinants influence the sexual behavior and perception of risk of MSM. Future studies should focus on the development of prevention strategies that address the complex motivations and meanings associated with sexual relations among MSM and should be innovative and consider the cultural and social contexts in which they live.

CONCLUSIONS

The fight against the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) remains a global public health challenge with significant impacts on key populations, particularly on Men who have Sex with Men (MSM). In Mexico, epidemiological data shows that this population presents a substantially higher risk of infection compared to the general population, which highlights the need for specific and culturally appropriate interventions. Despite advances in HIV prevention and treatment, the persistence of biological, psychological, social, and structural factors continues to hinder the eradication of the disease.

The use of condoms has become one of the most effective strategies in the prevention of HIV. However, its implementation faces multiple barriers, including the perception of decreased pleasure, lack of access to quality condoms, social pressure, and lack of education in sexual health. Evidence shows that it is necessary to address these obstacles comprehensively to promote safe sexual practices and reduce the incidence of HIV in MSM.

From a theoretical point of view, various psychological models have attempted to explain and predict HIV risk behaviors and prevention. Models such as Health Beliefs, Reasoned Action, Bandura's Social-Cognitive Model, and the Information-Motivation-Behavioural Skills Model have provided useful conceptual frameworks for designing effective interventions. However, there are still gaps in the understanding of the factors that influence the practices of MSM, which underlines the importance of continuing to develop research that integrates psychological, social, and cultural variables.

In epidemiological terms, HIV has evolved considerably since its appearance in the 1980s. Although mortality has decreased significantly thanks to access to antiretroviral treatment, the rate of new infections remains high, particularly in socially vulnerable populations. In Mexico, 99,6 % of new cases reported in 2023 were attributed to sexual transmission, indicating the urgency of strengthening prevention and early diagnosis strategies.

Biological determinants also play a key role in the vulnerability of MSM to HIV. The presence of sexually transmitted infections, unprotected anal sex, and the power dynamics within sexual relationships can increase the likelihood of transmission. In addition, psychosocial factors, such as stigma, discrimination, and marginalization, contribute to the difficulty of accessing health services and adopting effective preventive measures.

In conclusion, HIV prevention in MSM requires a comprehensive approach that considers biological, psychological, social, and structural factors. It is essential to continue promoting condom use, sexual health education, and equitable access to health services. Likewise, research should continue to explore innovative strategies to reduce barriers to access to HIV prevention and treatment in this key population.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Abeille Mora E, Soto Carrasco AA, Muñoz Muñoz VP, Sánchez Salinas R, Carrera Huerta S, Pérez Noriega E, et al. Características de la prueba piloto: Revisión de artículos publicados en enfermería. Rev Enferm Neurol. 2015;14(3):169–175. https://doi.org/10.37976/enfermeria.v14i3.212

2. Acosta Vergara TM. Riesgo percibido y decisión hacia la realización de prueba de VIH en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres en área metropolitana de Barranquilla 2020 [Tesis de grado]. Barranquilla: Universidad del Norte; 2021. Disponible en: http://manglar.uninorte.edu.co/bitstream/handle/10584/10136/1044431836.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

3. Agüero F, Masuet-Aumatell C, Morchon S, Ramon-Torrell J. Men who have sex with men: A group of travellers with special needs. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2019;28:74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.10.020

4. Ahumada-Cortez JG, Gámez-Medina ME, Valdez-Montero C. El consumo de alcohol como problema de salud pública. Rev Ra Ximhai. 2017;13(2):13–24. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/461/46154510001.pdf

5. Albarracín D, Johnson BT, Fishbein M, Muellerleile PA. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(1):142–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142

6. Ali MS, Tesfaye Tegegne E, Kassa Tesemma M, Tesfaye Tegegne K. Consistent condom use and associated factors among HIV-Positive clients on antiretroviral therapy in North West Ethiopian Health Center. AIDS Res Treat. 2019;1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7134908

7. Almanza Avendaño AM. Adherirse a la vida. Manual para promover la adherencia de varones con VIH. Editorial Colofón; 2018.

8. Amar Amar J, Abello Llanos R, Acosta C. Factores protectores: un aporte investigativo desde la psicología comunitaria de la salud. Rev Psicol Caribe. 2003;11:107–121. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/213/21301108.pdf

9. American Psychological Association [APA]. Society for Health Psychology. 2021. Disponible en: https://www.apa.org/about/division/div38

10. Andrew BJ, Mullan BA, de Wit JB, Monds LA, Todd J, Kothe EJ. Does the theory of planned behaviour explain condom use behaviour among men who have sex with men? A Meta-analytic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(12):2834–2844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1314-0

11. Antón Ruíz JA. Análisis de factores de riesgo para la transmisión del VIH/SIDA en adolescentes. Desarrollo de un modelo predictivo [Tesis Doctoral]. Universidad Miguel Hernández; 2013.

12. Ato García M, Vallejo Seco G. Diseños de investigación en Psicología. Pirámide Ed.; 2018.

13. Arias Duque R. Reacciones fisiológicas y neuroquímicas del alcoholismo. Diversitas Perspect Psicol. 2005;1(2):138–147. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=67910203

14. Bach Cabocho E, Forés Miravalles A. La asertividad. Para gente extraordinaria. Plataforma Editorial; 2010.

15. Baltar F, Gorjup M. Muestreo mixto online: Una aplicación en poblaciones ocultas. Intang Cap. 2012;8(1):123–149. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/549/54924517006.pdf

16. Bandura A. Self-efficacy. En: Ramachaudran VS, editor. Encyclopedia of human behavior. Vol. 4. New York: Academic Press; 1994. p. 71–81. Disponible en: https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura1994EHB.pdf

17. Bandura A. A social cognitive theory of personality. En: Pervin L, John O, editores. Handbook of personality. New York: Guilford Publications; 1999. p. 154–196. Disponible en: https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura1999HP.pdf

18. Bandura A. The evolution of social cognitive theory. En: Smith KG, Hitt MA, editores. Great Minds in Management. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. Disponible en: https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura2005.pdf

19. Bautista Arredondo S, Colchero A, Sosa Rubí SG, Romero Martínez M, Conde C. Resultados principales de la encuesta de seroprevalencia en sitios de encuentro de hombres que tienen sexo con hombres. México, D.F.: Funsalud; 2013. Disponible en: https://funsalud.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Encuesta-seroprevalencia.pdf

20. Becker MH, Maiman L. Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical recommendations. Med Care. 1975;13:10–24.

21. Betancourt Llody YA, Pérez Chacón D, Castañeda Abascal IE, Díaz Bernal Z. Riesgo de infección por VIH en hombres que tienen relaciones sexuales con hombres en Cuba. Rev Cubana Hig Epidemiol. 2021;58(1097). Disponible en: http://www.revepidemiologia.sld.cu/index.php/hie/article/view/1097/1072

22. Boza Cordero R. Orígenes del VIH/sida. Rev Clin Esc Med UCR-HSJD. 2016;6(4):48–60. Disponible ehttps://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/revcliescmed/ucr-2016/ucr164g.pdf

23. Boza Cordero R. Patogénesis del VIH. Rev Clin Esc Med UCR-HSJD. 2017;5(1):28–46. Disponiblen: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/revcliescmed/ucr-2017/ucr175a.pdf

24. Bravo AJ, Pilatti A, Pearson MR, Read JP, Mezquita L, Ibáñez MI. Cross-cultural examination of negative alcohol-related consequences: Measurement invariance of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire in Spain, Argentina, and USA. Psychol Assess. 2019;31(5):631–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000689

25. Buttmann N, Nielsen A, Munk C, Frederiksen K, Liaw K, Kjaer SK. Young age at first intercourse and subsequent risk-taking behaviour: An epidemiological study of more than 20,000 Danish men from the general population. Scand J Public Health. 2014;42(6):511–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494814538123

26. Cantu C, Surita K, Buendia J. Factors that increase risk of an HIV diagnosis following a diagnosis of syphilis: A Population-Based analysis of Texas Men. AIDS Behav. 2022;1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03593-w

27. Carvalho Gomes I, Gámez Medina M, Valdez Montero C. Chemsex y conductas sexuales de riesgo en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres: Una revisión sistemática. Health Addict Salud Drogas. 2020;20(1):158–165. Disponible en: https://ojs.haaj.org/?journal=haaj&page=article&op=view&path%5B%5D=495&path%5B%5D=pdf

28. Centro Nacional para la Prevención y Control del VIH/SIDA. Guía de manejo antirretroviral de las personas que viven con el VIH/SIDA. México; 2021. Disponible en: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/670762/Guia_ARV_2021.pdf

29. Chaves Dallelucci C, Carneiro Bragiato E, Nema Areco KC, Fidalgo F, Da Silveira DX. Sexual risky behavior, cocaine and alcohol use among substance users in an outpatient facility: a cross section study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2019;14(1):46-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/S13011-019-0238-X

30. Chávez Rodríguez E, Castillo Moreno RC. Revisión bibliográfica sobre VIH/SIDA. Multimed. 2013;17(4):189–213. Disponible en: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/multimed/mul-2013/mul134r.pdf

31. Chu Z, Xu J, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Hu Q, Yun K, et al. Poppers use and Sexual Partner Concurrency Increase the HIV Incidence of MSM: a 24-month Prospective Cohort Survey in Shenyang, China. Sci Rep. 2019;8:24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18127-x

32. Collins S, Walker C. HIV testing and risk of sexual transmission. I-Base. 2016. Disponible en: https://www.hivbirmingham.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/Test-trans-Jun2016e.pdf

33. Corral Gil GJ, García Campos ML, Herrera Paredes JM. Asertividad sexual, autoeficacia y conductas sexuales de riesgo en adolescentes: una revisión de la literatura. ACC CIETNA Rev Esc Enferm. 2022;9(2):167-177. Disponible en: https://revistas.usat.edu.pe/index.php/cietna/article/view/851/1579?download=pdf

34. Cross CP, Cyrenne DLM, Brown GR. Sex differences in sensation-seeking: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2013;3(2486). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep02486

35. Dacus J, Sandfort T. Perceived HIV risk among black MSM who maintain HIV-Negativity in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:3044–3055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02852-y

36. Dallelucci CC, Bragiato EC, Areco K, Fidalgo T, Da Silveira D. Sexual risky behavior, cocaine and alcohol use among substance users in an outpatient facility: a cross section study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2019;14(46). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-019-0238-x

37. Del Amo Valero, J., Coiras López, M.T., Díaz Franco, A. & Pérez Olmeda, M.T. (2017). VIH: La investigación contra la gran epidemia del siglo XX. Editorial Catarata.

38. Delgado, J.R., Segura, E.R., Lake, J.E., Sanchez, J., Lama, J.R., & Clark, J.L. (2017). Event-level analysis of alcohol consumption and condom use in partnership contexts among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Lima, Peru. Drug and alcohol dependence, 170 (2): 17-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.033

39. DiClemente, R. & Wingood, G. (1995). A Randomized Controlled Trial of an HIV Sexual Risk Reduction Intervention for Young African-American Women. Journal of the American Medical Association, 274(16), 1271-1276. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530160023028

40. Doggui, R., Wafaa, E., Conti, A. & Baldacchino, A. (2021). Association between chronic psychoactive substances use and systemic inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 125, 208-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.031

41. Dos Santos, W., Freitas, E., da Silva, A., Marinho, C., & Freitas, M. I. (2011). Barreiras e aspectos facilitadores da adesão à terapia antirretroviral em Belo Horizonte-MG. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 64(6), 1028-1037. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=267022538007

42. Duncan, D.T., Goedel, W.C., Stults, C.B., Brady, W.J., Brooks, F.A., Blakely, J.S., & Hagen, D. (2018). A study of intimate partner violence, substance abuse, and sexual risk behaviors among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with Men in a sample of geosocial-networking smartphone application users. American journal of men’s health, 12(2), 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988316631964

43. Enstad, F., Evans-Whipp. T., Kjeldsen, A., Toumbourou, J.W. & Von Soest, T. (2019). Predicting hazardous drinking in late adolescence/young adulthood from early and excessive adolescent drinking - A longitudinal cross-national study of Norwegian and Australian adolescents. BMC Public Health. 19(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7099-0

44. Encuesta Nacional de consumo de drogas, alcohol y tabaco. ENCODAT (2017a) Encuesta Nacional de consumo de drogas, alcohol y tabaco. 2017-2017. Reporte de Alcohol. Secretaria de Salud. https://encuestas.insp.mx/repositorio/encuestas/ENCODAT2016/doctos/informes/reporte_encodat_alcohol_2016_2017.pdf

45. Encuesta Nacional de consumo de drogas, alcohol y tabaco. ENCODAT (2017b) Encuesta Nacional de consumo de drogas, alcohol y tabaco. 2017-2017. Reporte de Alcohol. Secretaria de Salud. https://encuestas.insp.mx/repositorio/encuestas/ENCODAT2016/doctos/informes/reporte_encodat_drogas_2016_2017.pdf

46. Escrivá, N.G., Zurita, B. & Velasco, C (2017). Impacto clínico del chemsex en las personas con VIH. Revista Multidisciplinar del Sida, 5(11),21-31. https://www.revistamultidisciplinardelsida.com/download/numero-29-mayo-2023/

47. Espada, J.P., Lloret, D., García del Castillo, J.A., Gázquez Pertusa, M., & Méndez Carrillo, X. (2017). Psicología y sida: estrategias de prevención y tratamiento. En: Oblitas Guadalupe, L.A. Psicología de la Salud y Calidad de vida. 3ºed. Cengage Ed.

48. Estrada-Montoya, J. H. (2014). Hombres que tienen sexo con hombres (hsh): reflexiones para la prevención y promoción de la salud. Revista Gerencia y Políticas de Salud, 13(26), 44-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.RGYPS13-26.htsh

49. Fisher, C.M. (2011). Are information, motivation, and behavioral skills linked with HIV-related sexual risk among young men who have sex with men?. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 10, (1), 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15381501.2011.549064

50. Fisher, J.D., & Fisher, W.A. (1992). Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 111: 455-74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455

51. Fisher, J. D., Fisher, W. A., Amico, K. R., & Harman, J. J. (2006). An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychology, 25(4), 462–473. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462

52. Fisher, J.D., Fisher, W.A., Bryan, A.D., & Mishovich, S.J. (2002). Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model-Based Hiv Risk Behavior Change Intervention for Inner-City High School Youth. Health Psychology, 21(2), 177-186.

53. Gao M, Xiao C, Cao Y, Yu B, Li S, Yan H. Associations between sexual sensation seeking and AIDS-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among young men who have sex with men in China. Psychol Health Med. 2016;22(5):596-603.

54. García M. Factores de riesgo: una nada inocente ambigüedad en el corazón de la medicina conductual. Rev Aten Primaria. 1998;22(9):585-595. Disponible en: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-atencion-primaria-27-articulo-factores-riesgo-una-nada-inocente-14974

55. Guerras JM, Hoyos J, Agustí C, Casabona J, Sordo L, Pulido J, et al. Consumo sexualizado de drogas entre hombres que tienen sexo con hombres residentes en España. Adicciones. 2022;34(1):37-50. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.1371

56. González G. VIH: 30 años después... Salus. 2014;18(2):3-4. Disponible en: http://ve.scielo.org/pdf/s/v18n2/art01.pdf

57. González-Rivera J, Aquino-Serrano F, Ruiz-Quiñonez B, Matos-Acevedo J, Vélez-De la Rosa I, Burgos-Apunte-K, Rosario-Rodríguez K. Relación entre espiritualidad, búsqueda de sensaciones y conductas sexuales de alto riesgo. Rev Psicol. 2018;27(1):1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.5354/0719-0581.2018.50739

58. Gredig D, Le Breton M, Granados Valverde I, Solís Lara V. Predictores del uso del condón en hombres que tienen relaciones sexuales con hombres en Costa Rica: comprobación del modelo de información, motivación y habilidades conductuales. Rev Iberoam Cienc Salud. 2020;9(17):1-30. https://doi.org/10.23913/rics.v9i17.83

59. Guerra-Ordoñez JA, Benavides-Torres RA, Zapata-Garibay R, Ruiz-Cerino JM, Avila-Alpirez H, Salazar-Barajas ME. Percepción de riesgo para VIH y sexo seguro en migrantes de la frontera norte de México. Rev Int Androl. 2022;20(2). https://doi.org/10.10b16/j.androl.2020.10.010

60. Guerras JM, Hoyos J, Agustí C, Casabona J, Sordo L, Pulido J, et al. Consumo sexualizado de drogas entre hombres que tienen sexo con hombres residentes en España. Adicciones. 2022;34(1):37-50. Disponible en: https://www.adicciones.es/index.php/adicciones/article/viewFile/1371/1307

61. Gutiérrez S. Patrones de personalidad y asertividad sexual en agresores sexuales recluidos en cuatro centros penitenciarios de Perú. Cultura. Rev Asoc Docentes USMP. 2019;(33). https://doi.org/10.24265/cultura.2019.v33.15

62. Hentges B, Riva Knauth D, Vigo A, Barcellos Teixeira L, Fachel Leal A, Kendall C, et al. Inconsistent condom use with casual partners among men who have sex with men in Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720230019

63. Hernández Ávila CE, Carpio N. Introducción a los tipos de muestreo. ALERTA Rev Cient Inst Nac Salud. 2019;2(1):75-79. https://doi.org/10.5377/alerta.v2i1.7535

64. Hernández García R, Caudillo Ortega L, Flores Arias ML. Efecto del consumo de alcohol y homofobia internalizada en la conducta sexual en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres. Jóvenes Cienc Rev Divulg. 2017;3(2). Disponible en: http://www.sidastudi.org/resources/inmagic-img/DD47227.pdf

65. Hernández Sampieri R, Mendoza Torres CP. Metodología de la Investigación. Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta. Ed. McGraw Hill; 2018.

66. Herrera C, Kendall T, Campero L. Vivir con VIH en México. Experiencias de mujeres y hombres desde un enfoque de género. México: El Colegio de México; 2014.

67. Hibbert MP, Brett CE, Porcellato LA, Hope VD. Psychosocial and sexual characteristics associated with sexualised drug use and chemsex among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the UK. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95(5):342-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2018-053933

68. Jiang H, Chen X, Li J, Tan Z, Cheng W, Yang Y. Predictors of condom use behavior among men who have sex with men in China using a modified information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6593-8

69. Jiang H, Li J, Tan Z, Cheng W, Yang Y. The moderating effect of sexual sensation seeking on the association between alcohol and popper use and multiple sexual partners among men who have sex with men in Guangzhou, China. Subst Use Misuse.

70. Jiménez Vázquez V. Modelo de sexo seguro para hombres que tienen sexo con hombres [Tesis de doctorado]. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León; 2018.

71. Jose J, Sakboonyarat B, Kana K, Chuenchitra T, Sunantarod A, Meesiri S, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection and related risk factors among young Thai men between 2010 and 2011. PLoS One. 2020;15(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237649

72. Kalichman SC, Johnson JR, Adair V, Rompa D, Multhauf K, Kelly JA. Sexual Sensation Seeking: Scale development and predicting AIDS-Risk behavior among homosexually active men. J Pers Assess. 1994;62(3):385-397.

73. Kritsanavarin U, Bloss E, Manopaiboon C, Khawcharoenporn T, Harnlakon P, Vasanti-Uppapokakorn M, et al. HIV incidence among men who have sex with men and transgender women in four provinces in Thailand. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31(12):1154–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462420921068

74. Lameiras Fernández M, Rodriguez Castro Y, Dafonte Pérez S. Evolución de la percepción de riesgo de la transmisión heterosexual del VIH en universitarios/as españoles/as. Psicothema. 2002;14(2):255-261. https://www.psicothema.com/pdf/717.pdf

75. Leddy A, Chakravarty D, Dladla S, de Bruyn G, Darbes L. Sexual communication self-efficacy, hegemonic masculine norms and condom use among heterosexual couples in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2016;28(2):228-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2015.1080792

76. Leonangeli S, Rivarola Montejano G, Michelini Y. Impulsividad, consumo de alcohol y conductas sexuales riesgosas en estudiantes universitarios. Rev Fac Cienc Med Córdoba. 2021;78(2):153-157. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8741313/pdf/1853-0605-78-2-153.pdf

77. Li D, Yang X, Zhang Z, Qi X, Ruan Y, Jia Y, et al. Nitrite inhalants use and HIV infection among men who have sex with men in China. Biomed Res Int. 2014;365261. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/365261

78. Llanes García L, Peñate Gaspar A, Medina Pérez J. Percepción de riesgo sobre VIH-SIDA en estudiantes becarios de primer año de Medicina. Medicent Electrón. 2020;24(1):185-191. http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/mdc/v24n1/1029-3043-mdc-24-01-185.pdf

79. Lomba L, Apóstolo J, Mendes F. Consumo de drogas, alcohol y conductas sexuales en los ambientes recreativos nocturnos de Portugal. Adicciones. 2009;21(4):309-326.

80. López-Sánchez U, Onofre-Rodríguez DJ, Torres-Obregon R, Benavides-Torres RA, Garza-Elizondo ME. Hipermasculinidad y uso de condón en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres y mujeres. Health Addict Salud Drogas. 2021;21(1):63-75. https://doi.org/10.21134/haaj.v21i1.510

81. Marcus U, Gassowski M, Drewes J. HIV risk perception and testing behaviours among men having sex with men (MSM) reporting potential transmission risk in the previous 12 months from a large online sample of MSM living in Germany. Public Health. 2016;16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3759-5

82. Martinez O, Muñoz-Laboy M, Levine TS, Dolezal C, Dodge B, Icard L, et al. Relationship factors associated with sexual risk behavior and high-risk alcohol consumption among Latino men who have sex with men: Challenges and opportunities to intervene on HIV risk. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46(4):987-999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0835-y

83. Matarelli S. Sexual Sensation Seeking and Internet Sex-Seeking of Middle Eastern Men Who Have Sex with Men. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(7):1285-1297.

84. Medrano L, Pérez E. Manual de Psicometría y Evaluación Psicológica. Ed. Brujas; 2019.

85. Mendoza-Pérez JC, Ortiz-Hernández L. Factores asociados con el uso inconsistente de condón en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres de Ciudad Juárez. Rev Salud Pública. 2009;11(5):700-712. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42217809003

86. McCree DH, Oster AM, Jeffries IV WL, Denson DJ, Lima AC, Whitman H, et al. HIV acquisition and transmission among men who have sex with men and women: what we know and how to prevent it. Prev Med. 2017;100:132-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.024

87. McKenney J, Sullivan PS, Bowles KE, Oraka E, Sanchez TH, DiNenno E. HIV risk behaviors and utilization of prevention services, urban and rural men who have sex with men in the United States: Results from a National Online Survey. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(7):2127-2136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1912-5

88. Milanes Sousa L, Ciabotti Elias, De Sousa Caliaria J, Cunha de Oliveira A, Gir E, Reis RK. Inconsistent use of male condoms among HIV-negative men who have sex with other men. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2023;31. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.6327.3891

89. Morell Mengual V, Gil Llario MD, Fernández García O, Balleste Arnal R. Factors Associated with Condom Use in Anal Intercourse Among Spanish Men Who Have Sex with Men: Proposal for an Explanatory Model. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(11):3836-3845. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03282-0

90. Morosini E. Estudio de seroprevalencia de VIH/SIDA y sífilis, factores socio comportamentales y estimación del tamaño de la población de hombres que tienen sexo con hombres en 6 regiones del Paraguay. 2011. Disponible en: https://acortar.link/tNdtqE.

91. Morokoff PJ, Quina K, Harlow LL, Whitmire L, Grimley DM, Gibson PR, Burkholder GJ. Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS) for women: development and validation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(4):790. Disponible en: https://web.archive.org/web/20170808030614id_/http://www.psychwiki.com/dms/other/labgroup/Measufsdfsdbger345resWeek1/Marliyn/Morokoff1997.pdf

92. Neal DJ, Fromme K. Event-Level Covariation of Alcohol Intoxication and Behavioral Risks During the First Year of College. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;(2):294–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.294

93. Nesoff ED, Dunkle K, Lang D. The impact of condom use negotiation self-efficacy and partnership patterns on consistent condom use among college-educated women. Health Educ Behav. 2016;43(1):61-67. https://doi.org/0.1177/1090198115596168

94. Morokoff PJ, Quina K, Harlow LL, Whitmire L, Grimley DM, Gibson PR, Burkholder GJ. Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS) for women: development and validation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(4):790. Disponible en: https://web.archive.org/web/20170808030614id_/http://www.psychwiki.com/dms/other/labgroup/Measufsdfsdbger345resWeek1/Marliyn/Morokoff1997.pdf

95. Neal DJ, Fromme K. Event-Level Covariation of Alcohol Intoxication and Behavioral Risks During the First Year of College. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;(2):294–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.294

96. Nesoff ED, Dunkle K, Lang D. The impact of condom use negotiation self-efficacy and partnership patterns on consistent condom use among college-educated women. Health Educ Behav. 2016;43(1):61-67. https://doi.org/0.1177/1090198115596168

97. Ntombela NP, Kharsany A, Nonhlanhla YZ, Kohler HP, McKinnon LR. Prevalence and Risk Factors for HIV Infection Among Heterosexual Men Recruited from Socializing Venues in Rural KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:3528-3537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03182-3

98. Ober A, Dangerfield D, Shoptaw S, Ryan G, Stucky B, Friedman S. Using a “Positive Deviance” Framework to Discover Adaptive Risk Reduction Behaviors Among High-Risk HIV Negative Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:1699-1712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1790-x

99. Oblitas Guadalupe LA. Psicología de la Salud y Calidad de Vida. Cengage Editorial; 2017.10º shri A, Tubman JG, Morgan-Lopez AA, Saavedra LM, Csizmadia A. Sexual sensation seeking, co-occurring sex and alcohol use, and sexual risk behavior among adolescents in treatment for substance use problems. Am J Addict. 2013;22(3):197-205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.12027.x

100. Osorio Leyva A, Álvarez Aguirre A, Hernández Rodríguez VM, Sánchez Perales M, Muñoz Alonso LR. Relación entre asertividad sexual y autoeficacia para prevenir el VIH/SIDA en jóvenes universitarios del área de la salud. RIDE. Rev Iberoam Investig Desarr Educ. 2017;7(14):1-14. https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v7i14.264

101. Ottaway Z, Finnerty F, Amlani A, Pinto-Sander N, Szanyi J, Richardson D. Men who have sex with men diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection are significantly more likely to engage in sexualised drug use. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(1):91-93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462416666753

102. Pastor Y, Rojas-Murcia C. A comparative research of sexual behaviour and risk perception in two cohorts of Spanish university students. Univ Psychol. 2019;18(3):1-14. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy18-3.crsb

103. Patel EU, White JL, Gaydos CA, Quinn TC, Mehta SH, Tobian AAR. Marijuana Use, Sexual Behaviors, and Prevalent Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Sexually Experienced Males and Females in the United States: Findings From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Sex Transm Dis. 2020;47(10):672–678. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001229

104. Pérez Ortiz R. Información, motivación y habilidades conductuales en el comportamiento de riesgo para VIH-SIDA en hombres y mujeres en edad productiva adscritos a la Unidad de Medicina Familiar #1, Delegación Aguascalientes [Tesis de doctorado]. Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes; 2021. Disponible en: http://bdigital.dgse.uaa.mx:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11317/2022/452424.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

105. Pérez Rosabal E, Soler Sánchez YM, Pérez Rosabal R, López Arias E, Leyva Rodríguez VV. Conocimientos sobre VIH/sida, percepción de riesgo y comportamiento sexual en estudiantes universitarios. Multimed. 2016;20(1):1-14. Disponible en: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/multimed/mul-2016/mul161b.pdf

106. Pilatti A, Read JP, Pautassi RM. ELSA 2016 cohort: Alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use and their association with age of drug use onset, risk perception, and social norms in Argentinean college freshmen. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1452. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01452

107. Plascencia-De la Torre JC, Chan-Gamboa EC, Salcedo-Alfaro JM. Variables psicosociales predictoras de la no adherencia a los antirretrovirales en personas con VIH-SIDA. Rev CES Psicol. 2019;12(3):67-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.21615/cesp.12.3.5

108. Ponce de León RS. Inicio de la pandemia. En: Centro de Investigación en Enfermedades Infecciosas [CIENI]. 30 años del VIH-SIDA. Perspectiva desde México. 2011.

109. Posada Zapata IC, Yepes Delgado CE, Patiño Olarte LM. Amor, riesgo y Sida: hombres que tienen sexo con hombres. Rev Estud Fem. 2020;28(1):1-13. https://www.scielo.br/j/ref/a/RB4hw7z6sNvzz9BRtVwh3Jf

110. Prabhu S, Harwell J, Kumarasamy N. Advanced HIV: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Lancet HIV. 2019;6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30189-4

111. Programa Conjunto de las Naciones Unidas sobre el VIH SIDA. ONUSIDA. Aprovechando el momento. La respuesta al VIH en América Latina. 2020. Disponible en: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_global-aids-report-latin-america_es.pdf

112. Programa Conjunto de las Naciones Unidas sobre el VIH SIDA. ONUSIDA. Hoja Informativa. Estadísticas mundiales sobre el VIH. 2023. Disponible en: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_es.pdf

113. Ramchandani MS, Golden MR. Confronting rising STIs in the era of PrEP and treatment as prevention. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16:244–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-019-00446-5

114. Reidl Martínez LM, Guillén Riebeling RS. Diseños multivariados de investigación en ciencias sociales. UNAM; 2019.

115. Reis RK, Melo ES, Fernandes NM, Antonini M, Neves LAS, Gir E. Inconsistent condom use between serodifferent sexual partnerships to the human immunodeficiency virus. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2019;27:e3222. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.3059.3222

116. Resnick D, Morales K, Gross R, Petsis D, Fiore D, Davis-Vogel A, et al. Prior sexually transmitted infection and human immunodeficiency virus risk perception in a diverse at-risk population of men who have sex with men and transgender individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2021;35(1):15-22. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2020.0179

117. Restrepo Pineda JE, Villegas Rojas S. Factores asociados con el uso del condón en trabajadoras y trabajadores sexuales de origen venezolano en Colombia. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2023;47:1-7. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2023.2

118. Rodríguez Vázquez N, López García K, Rodríguez Aguilar L, Guzmán Facundo F. Inhibición de respuesta y su relación con el consumo de alcohol en estudiantes de bachillerato. XVI Coloquio Panamericano de Investigación en Enfermería, Cuba. 2018. Disponible en: https://coloquioenfermeria2018.sld.cu/index.php/coloquio/2018/paper/viewFile/463/355

119. Rojas Concepción AA. 40 años de una pandemia aún presente: el VIH-SIDA. Rev Cien Med Pinar del Río. 2021;25(4). Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/rpr/v25n4/1561-3194-rpr-25-04-e5225.pdf

120. Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1966;2:354-386. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/109019817400200405

121. Sanabria-Mazo JP, Hoyos-Hernández PA, Bravo F. Psychosocial factors associated with HIV testing in Colombian university students. Acta Colomb Psicol. 2020;23(1):158-168. http://www.doi.org/10.14718/ACP.2020.23.1.8

122. Sánchez Medina R, Enríquez Negrete DJ, Rosales Piña CR. Modelo de apoyo y resiliencia sexual sobre el uso del condón en hombres que viven con VIH. En: Castillo Arcos LC, Maas Góngora L, Telumbre Terrero JY, eds. Psicología Social en México. Universidad Autónoma del Carmen.

123. Sánchez Medina R, Enríquez Negrete DJ, Rosales Piña CR, Pérez Martínez PU. Diseño y validación de dos escalas de comunicación sexual con la pareja en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres. Pensando Psicol. 2021;17(2):1-31. https://doi.org/10.16925/2382-3984.2021.02.01

124. Sánchez Medina R, Lozano Quiroz MF, Negrete Rodríguez OI, Enríquez Negrete DJ, Estrada Martínez MA. Validación de la escala de percepción de riesgo ante el VIH (EPR- VIH) en hombres. Rev Psicol. 2021;20(2):34–54. http://doi.org/10.24215/2422572Xe110.

125. Santillán Torres Torija C. Adherencia terapéutica en personas que viven con VIH-SIDA. [Tesis de grado]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 2014. Disponible en: http://132.248.10.225:8080/bitstream/handle/123456789/76/62.pdf?sequence=1

126. Santos-Iglesias P, Sierra JC. El papel de la asertividad sexual en la sexualidad humana: una revisión sistemática. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2010;10(3):553-77. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/337/33714079010.pdf

127. Saura S, Jorquera V, Rodríguez D, Mascort C, Castella I, García J. Percepción del riesgo de infecciones de transmisión sexual/VIH en jóvenes desde una perspectiva de género. Aten Primaria. 2019;51(2):61-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2017.08.005

128. Secretaría de Salud. Reglamento de la Ley General de Salud en Materia de Investigación para la Salud (Núm. 141). Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2014. Disponible en: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/regley/Reg_LGS_MIS.pdf

129. Secretaría de Salud. Sistema de vigilancia epidemiológica de VIH. Informe histórico de VIH 4to trimestre 2023. 2023. Disponible en: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/909291/VIH_DVEET_4toTrim_2023.pdf

130. Senado Dumoy J. Los factores de riesgo. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr. 1999;15(4):446-52. Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-21251999000400018&lng=es&tlng=es

131. Shadaker S, Magee M, Paz-Bailey G, Hoots BE, NHBS Study Group. Characteristics and risk behaviors of men who have sex with men and women compared with men who have sex with men—20 US cities, 2011 and 2014. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75:281-7. http://10.1097/QAI.0000000000001403

132. Sharp P, Hahn B. The evolution of HIV-1 and the origin of AIDS. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2010;365(552):2487–94.

133. Schecke H, Lea T, Bohn A, Köhler T, Sander D, Scherbaum N, Deimel D. Crystal Methamphetamine Use in Sexual Settings Among German Men Who Have Sex with Men. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:886. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00886

134. Sierra JC, Vallejo Medina P, Santos Iglesias P. Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española de la Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS). An Psicol. 2011;27(1):17-26. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/167/16717018003.pdf

135. Skidmore CR, Kaufman EA, Crowell SE. Substance use among college students. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016;25(4):735-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2016.06.004

136. Stover J, Teng Y. The impact of condom use on the HIV epidemic. Gates Open Res. 2022;5:91. https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.13278.2

137. Sullivan S, Stephenson R. Perceived HIV prevalence accuracy and sexual risk behavior among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(6):1849-57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1789-3

138. Supo J. Seminarios de Investigación Científica: Metodología de la Investigación para Las Ciencias de la Salud. Createspace Independent Pub; 2012.

139. Tan R, Kaur N, Chen M, Wong C. Individual, interpersonal, and situational factors influencing HIV and other STI risk perception among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: a qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2020;32(12):1538-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1734176

140. Terroni NN. La comunicación y la asertividad del discurso durante las interacciones grupales presenciales y por computadora. Psico-Usf. 2009;14(1):35-46. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-82712009000100005

141. Tobón BA, García Peña JJ. VIH: Una mirada a la luz de lo psicosocial. Psicol Salud. 2022;32(2):215-25. https://doi.org/10.25009/pys.v32i2.2743

142. Tomkins A, George R, Kliner M. Sexualised drug taking among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2018;139(1):23-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913918778872

143. Torres Obregón R, Onofre Rodríguez DJ, Benavides Torres RA, Calvillo C, Garza Elizondo ME, Telumbre Terrero JY. Riesgo percibido y balance decisional hacia la prueba del VIH en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres de Monterrey, México. Enferm Clin. 2018;28(6):394-400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2018.06.008.

144. Torres Obregón R, Onofre Rodríguez D, Sierra JC, Benavidez Torrez RA, Garza Elizondo ME. Validación de la Sexual Assertiveness Scale en mujeres mexicanas. Suma Psicológica. 2017;24:34-41. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1342/134252832005.pdf

145. Uribe JI, Andrade PP, Zacarías SX, Betancourt OD. Predictores del uso del condón en las relaciones sexuales de adolescentes, análisis diferencial por sexo. Rev Intercont Psicol Educ. 2013;15(2):75-92. https://salutsexual.sidastudi.org/resources/inmagic-img/DD65373.pdf

146. Uribe-Alvarado JI, Bahamón MJ, Reyes-Ruíz L, Trejos-Herrera A, Alarcón-Vásquez Y. Percepción de autoeficacia, asertividad sexual y práctica sexual protegida en jóvenes colombianos. Acta Colombiana de Psicología. 2017;20(1):203-211. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/798/79849735010.pdf

147. Uribe Rodríguez AF. Evaluación de factores psicosociales de riesgo para la infección por el VIH SIDA en adolescentes colombianos. [Tesis de Doctorado]. Universidad de Granada; 2005.

148. Valdez Montero C. Modelo de conducta sexual en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres. Tesis de posgrado]. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México; 2015.

149. Valdez Montero C, Benavidez Torres R, González González V, Onofre Rodríguez D, Castillo Arcos L. Internet y conducta sexual de riesgo para VIH/SIDA en jóvenes. Enferm Glob. 2015;38:151-159. https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/eg/v14n38/docencia3.pdf

150. Valdez Montero C, Castillo Arcos L, Olvera Blanco A, Onofre Rodríguez DJ, Caudillo Ortega L. Reflexión de los determinantes sociales de la conducta sexual en hombres que tienen relaciones sexuales con hombres. Cuid Enferm Educ Salud. 2015;2(1):34-47. http://www.sidastudi.org/es/registro/a53b7fb35964dafc0159db90274e020b

151. Valencia J, Gutiérrez J, Troya J, González A, Dolengevich H, Cuevas G, Ryan P. Consumo de drogas recreativas y sexualizadas en varones negativos: datos desde un screening comunitario de VIH. Rev Multidiscip SIDA. 2018;6(13):1-13. https://www.sidastudi.org/resources/inmagic-img/DD49157.pdf

152. Valencia González M, Trujillo E. VIH, la otra pandemia. Ciencias. 2021;28-29.

153. Vallée A. Sexual behaviors, cannabis, alcohol and monkeypox infection. Front Public Health. 2023;10:1054488. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1054488

154. Wang W, Yan H, Duan Z, Yang H, Li X, Ding C, et al. Relationship between sexual sensation seeking and condom use among young men who have sex with men in China: Testing a moderated mediation model. AIDS Care. 2021;33(7):914-919. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1808156

155. Waugh M. The role of condom use in sexually transmitted disease prevention: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(5):549-552. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CLINDERMATOL.2010.03.014

156. Wim VB, Christiana N, Marie L. Syndemic and other risk factors for unprotected anal intercourse among an online sample of Belgian HIV negative men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):50–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0516-y

157. Xu JJ, Qian HZ, Chu ZX, et al. Recreational drug use among Chinese men who have sex with men: a risky combination with unprotected sex for acquiring HIV infection. Biomed Res Int. 2014;14:642. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/725361

158. Xu W, Zheng L, Liu Y, Zheng Y. Sexual sensation seeking, sexual compulsivity, and high-risk sexual behaviours among gay/bisexual men in Southwest China. AIDS Care. 2016;28(9):1138-1144. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1153587

159. Yañez C. Columna de Salud: La falta de percepción de riesgo explican aumentos de los casos de VIH. La Tercera. 2018. https://www-proquest-com.wdg.biblio.udg.mx:8443/docview/2289787497/B796E7E54F4E42F9PQ/1?accountid=28915

160. Zamboni BD, Crawford I, Williams PG. Examining communication and assertiveness as predictors of condom use: Implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12:492-504.

161. Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking. En: Leary MR, Hoyle RH, editores. Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. New York: The Guildford Press; 2009. p. 455-465.

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Juan Carlos Plascencia-De la Torre, Kalina Isela Martínez-Martínez, Fredi Everardo Correa-Romero, Ricardo Sánchez-Medina, Oscar Ulises Reynoso-González.

Data curation: Juan Carlos Plascencia-De la Torre, Kalina Isela Martínez-Martínez, Fredi Everardo Correa-Romero, Ricardo Sánchez-Medina, Oscar Ulises Reynoso-González.

Formal analysis: Juan Carlos Plascencia-De la Torre, Kalina Isela Martínez-Martínez, Fredi Everardo Correa-Romero, Ricardo Sánchez-Medina, Oscar Ulises Reynoso-González.

Drafting - original draft: Juan Carlos Plascencia-De la Torre, Kalina Isela Martínez-Martínez, Fredi Everardo Correa-Romero, Ricardo Sánchez-Medina, Oscar Ulises Reynoso-González.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Juan Carlos Plascencia-De la Torre, Kalina Isela Martínez-Martínez, Fredi Everardo Correa-Romero, Ricardo Sánchez-Medina, Oscar Ulises Reynoso-González.