doi: 10.56294/mw2024476

ORIGINAL

Protective and risk factors for condom use as an HIV preventive measure in men who have sex with men, development of a model

Factores protectores y de riesgo para el uso del condón como medida preventiva del VIH en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres, desarrollo de un modelo

Juan Carlos Plascencia-De la Torre1

![]() *, Kalina Isela Martínez-Martínez2

*, Kalina Isela Martínez-Martínez2

![]() , Fredi Everardo Correa-Romero3

, Fredi Everardo Correa-Romero3

![]() , Ricardo Sánchez-Medina4

, Ricardo Sánchez-Medina4

![]() , Oscar Ulises Reynoso-González1

, Oscar Ulises Reynoso-González1

![]() *

*

1Universidad de Guadalajara. Guadalajara, México.

2Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, Departamento de psicología. Aguas calientes, México.

3Universidad de Guanajuato. México.

4Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México.

Cite as: Plascencia-De la Torre JC, Martínez-Martínez KI, Correa-Romero FE, Sánchez-Medina R, Reynoso-González OU. Protective and risk factors for condom use as an HIV preventive measure in men who have sex with men, development of a model. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2024; 3:476. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw2024476

Submitted: 29-09-2023 Revised: 19-02-2024 Accepted: 05-05-2024 Published: 06-05-2024

Editor: PhD.

Prof. Estela Morales Peralta ![]()

Corresponding Author: Juan Carlos Plascencia-De la Torre *

ABSTRACT

Introduction: HIV continues to disproportionately affect key populations, such as MSM, who in Mexico have a 28 times higher risk of infection compared to other key populations and 44 times higher than the general population (CENSIDA, 2021). This vulnerability is due to the interaction of psychological, social and structural factors that interfere with preventive behaviors, such as condom use (Tobón & García, 2022).

Objective: to evaluate the influence of protective psychological factors (HIV risk perception and sexual assertiveness) and risk factors (sexual sensation seeking and psychoactive substance use) on condom use as an HIV preventive measure in a sample of MSM in the state of Jalisco, Mexico.

Method: a quantitative study with a non-experimental-transversal design and predictive-exploratory scope was carried out with the participation of 247 MSM of legal age from Jalisco. A battery of instruments was used that included the HIV Risk Perception Scale, the Sexual Assertiveness Scale, the Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale, the Alcohol and Drug Consumption subscale of the Questionnaire of Situational Influences for Sexual Behavior in MSM, and two items to measure consistency in condom use. Data were collected digitally, respecting ethical standards, and descriptive, bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed.

Results: consistent condom use was reported by 37,7 % of participants. Moderate to high levels of HIV risk perception and sexual assertiveness, and low levels of sexual sensation seeking and substance use were observed. Condom use was positively correlated with risk perception and sexual assertiveness. The logistic regression model was significant (p < 0,001), showing that the higher the risk perception and assertiveness, the higher the probability of condom use, explaining between 21,6 % and 29,5 % of the variance.

Conclusions: it is concluded that HIV risk perception and sexual assertiveness are key factors that positively influence consistent condom use in the MSM population. The predictive model demonstrates that as these factors increase, the likelihood of consistent condom use significantly increases, underscoring the importance of promoting educational strategies that strengthen HIV risk awareness and sexual assertiveness skills.

Keywords: Risk Perception; Sexual Assertiveness; Condom Use; Sexual Sensation Seeking; Consumption of Psychoactive Substances.

RESUMEN

Introducción: el VIH continúa afectando de manera desproporcionada a poblaciones clave, como los HSH, quienes en México tienen un riesgo 28 veces mayor de infección en comparación con otras poblaciones clave y 44 veces mayor que la población general (CENSIDA, 2021). Esta vulnerabilidad se debe a la interacción de factores psicológicos, sociales y estructurales que interfieren con las conductas preventivas, como el uso del condón (Tobón & García, 2022).

Objetivo: evaluar la influencia de los factores psicológicos protectores (percepción de riesgo al VIH y la asertividad sexual) y de riesgo (búsqueda de sensaciones sexuales y consumo de sustancias psicoactivas) sobre el uso del condón como medida preventiva del VIH en una muestra de HSH en el estado de Jalisco, México.

Método: se realizó un estudio cuantitativo con diseño no experimental-transversal y alcance predictivo-explicativo, en el que participaron 247 HSH mayores de edad de Jalisco. Se utilizó una batería de instrumentos que incluyó la Escala de Percepción de Riesgo al VIH, la Escala de Asertividad Sexual, la Escala de Búsqueda de Sensaciones Sexuales, la subescala de Consumo de Alcohol y Drogas del Cuestionario de Influencias Situacionales para la Conducta Sexual en HSH, y dos reactivos para medir la consistencia en el uso del condón. Los datos se recopilaron digitalmente, respetando las normas éticas, y se realizaron análisis descriptivos, bivariados y multivariados.

Resultados: el 37,7 % de los participantes reportó un uso consistente del condón. Se observaron niveles moderados a altos en la percepción de riesgo al VIH y la asertividad sexual, y niveles bajos en la búsqueda de sensaciones sexuales y el consumo de sustancias. El uso del condón se correlacionó positivamente con la percepción de riesgo y la asertividad sexual. El modelo de regresión logística fue significativo (p < 0,001), mostrando que, a mayor percepción de riesgo y asertividad, mayor es la probabilidad de usar condón, explicando entre el 21,6 % y el 29,5 % de la varianza.

Conclusiones: se concluye que la percepción de riesgo al VIH y la asertividad sexual son factores clave que influyen positivamente en el uso consistente del condón en la población de HSH. El modelo predictivo demuestra que, a medida que aumentan estos factores, se incrementa significativamente la probabilidad de utilizar el condón de manera consistente, lo que subraya la importancia de promover estrategias educativas que fortalezcan la conciencia sobre el riesgo del VIH y las habilidades de asertividad sexual no estructurado, con una extensión no mayor a 250 palabras; redactado en pasado y en tercera persona del singular.

Palabras clave: Percepción de Riesgo; Asertividad Sexual; Uso del Condón; Búsqueda de Sensaciones Sexuales; Consumo de Sustancias Psicoactivas.

INTRODUCTION

Health Psychology is fundamental in studying the psychosocial factors associated with health risk behaviors. Several theoretical models point to variables that influence the adoption of behaviors to prevent HIV, so knowledge of them helps plan, implement, and evaluate programs to modify HIV-related health behaviors in key populations. However, there are gaps in the literature that make it challenging to understand condom use among the MSM population in Mexico. These include psychological factors that have not been explored in the Mexican context, and that could explain the risk processes associated with HIV acquisition, such as the perception of HIV risk, sexual assertiveness, the search for sexual sensations, and the consumption of psychoactive substances. Given this fact, it is necessary to ask the following question: Of the factors mentioned above, which are most associated with condom use among MSM in the state of Jalisco in Mexico?

To answer the question posed, this thesis developed a quantitative-cross-sectional study with an explanatory and predictive scope that allowed the association of the independent variables with the dependent variable to be established, in this case, the consistent use of condoms. Under this methodology, advanced statistical tools allowed a rigorous data analysis, identifying relationships between the variables. Given their focus on objectivity and precision, quantitative studies tend to be easier to replicate, which increases confidence in the results. The sections into which this doctoral thesis is broken down are described below.

The first section deals with the problem statement and the justification for the study, examining the topic's relevance within the field of psychological science. This research's importance is highlighted, emphasizing its contribution to existing knowledge and its potential to answer questions not yet explored in the discipline. To guide this research, the research question is formulated to shed light on the protective and risk factors associated with condom use in a sample of MSM. This question is posed to orient the study toward obtaining clear and well-founded answers that contribute to the development of knowledge in psychology. The general and specific objectives designed to direct the concrete actions carried out during the research process are integrated.

Subsequently, in section two, the theoretical and empirical background that supports the research work is detailed, divided into three chapters: the first describes the generalities of HIV, its conceptualization, means of transmission, diagnosis, treatment and the most current epidemiological data at the global, national and state levels, as well as mentioning the main theoretical models that explain HIV risk behavior; the second chapter provides a review of the concept of MSM as a key population for acquiring HIV, as well as the risk rate in Latin America and Mexico, followed by some recent studies that account for the public health problem in which this population is immersed, and the risk factors for HIV infection; in the third chapter of this thesis, the subject of condom use is explored in depth, focusing on recent empirical studies carried out in key populations, various factors associated with condom use are analyzed, with a particular focus on protective and risk factors such as perception of HIV risk, sexual assertiveness, the search for sexual sensations and the consumption of psychoactive substances. The method is emphasized in section three, detailing aspects such as the design, the characterization of the participants, the measurement instruments, the procedures, the statistical analyses used to test the research hypotheses, and the ethical considerations of the study.

Section four details the results obtained in the study, starting with the descriptive statistics of the study variables, followed by a correlation analysis and finally, the application of a binary logistic regression analysis that allowed us to predict the probability of condom use in MSM based on the study variables: perception of HIV risk, sexual assertiveness, the search for sexual sensations and the consumption of psychoactive substances.

Finally, section five presents the discussion, in which the results are interpreted and contextualized within the existing literature. It exposes the relationship of the findings with previous studies, highlighting similarities, differences, practical implications, and relevance for the field of health psychology. In addition, the main conclusions of the doctoral thesis work are addressed, and the study's limitations are explained transparently, explaining how they could have affected the results and proposing recommendations for future research.

What protective psychological factors (perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness) and risk factors (search for sexual sensations and consumption of psychoactive substances) are associated with condom use in a sample of MSM in the state of Jalisco?

Objective

To evaluate the association of protective psychological factors (perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness) and risk factors (search for sexual sensations and consumption of psychoactive substances) on the use of condoms as a preventive measure against HIV in a sample of MSM in the state of Jalisco, Mexico.

METHOD

Considering the review of the literature and with the aim of answering the research questions, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H1: Moderate levels of perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness will be found among the MSM evaluated, with appreciable variability in these levels. Likewise, high levels of seeking sexual sensations and consumption of psychoactive substances are expected. As for condom use, it will be inconsistent in most MSM during sexual intercourse, with observable variability in this behavior.

H2: There is a positive relationship between the perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness with the consistency index in the use of condoms, as well as a negative correlation between the

Search for sexual sensations and the consumption of psychoactive substances with the consistency index in the use of condoms in the MSM sample.

H3: The perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness have a positive influence. In contrast, the search for sexual sensations and the consumption of psychoactive substances hurt the consistency of condom use in the sexual relations of the MSM evaluated.

Operationalization of the variables

Table 1 below presents the operational definition of the variables that form part of the study for the development of the model, including the classification of the variable according to its measurement, the instruments used to collect the information, as well as its characterization and, finally, the indicators to be obtained.

|

Table 1. Operational definition of the research variables |

|||

|

Variable |

Definition |

Indicators |

Instrument |

|

Percepción de Riesgo al VIH Predictive |

It is understood as the vulnerability perceived by an individual when considering whether or not they are at risk of contracting a disease. |

Total score on the risk perception scale and its three main factors: risky sexual practices, HIV transmission situation and safe sexual practices. |

Scale of risk perception of HIV transmission through sex [EPR-VIH] (Sánchez, Lozano, et al. 2021). 16 items with Likert-type response options 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. Reliability indices (α = 0,71; ω = 0,71). |

|

Sexual Assertiveness Predictive |

It is a social skill that allows you to communicate sexual preferences, needs or opinions to another person. |

Total score on the sexual assertiveness scale and its three components: Initiation of sexual intercourse, Refusal of sexual intercourse and prevention of HIV and other STIs. |

Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS) designed by Morokoff et al. (1997), adapted into Spanish by Sierra et al. (2011) and validated in the Mexican population by Torres et al. (2017). It is made up of 18 items with Likert-type response options from 0 = Never to 4 = Always. Reliability indexes (α = 0,81; ω = 0,81). |

|

Search for Sexual Sensations Predictive |

Personality trait in which there is a predisposition of the person to experience new sensory stimulations, even when there are certain risks involved. |

Average score on the scale of the search for sexual sensations. |

Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale (SSSS-9) by Kalichman et al. (1995) adapted into Spanish and validated in Mexican adults by Moral de la Rubia (2018). Composed of 9 Likert-type items 1 = Strongly disagree to 4 = Strongly agree. Reliability indexes (α = 0,80; ω = 0,81). |

|

Consumption of Psychoactive Substances Predictor |

Use of chemical substances that alter the normal functioning of the central nervous system and can affect the mood, emotions, behavior and perception of reality of any individual. |

Average score on the substance use subscale, as well as the frequency of alcohol and drug use. |

Subscale of substance use from the Situational Influences on Sexual Behavior for Men Who Have Sex with Men (ISCS_MSM; Moral de la Rubia et al., 2016) questionnaire, validated in the Mexican population. Composed of 8 items. Items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7 are in Likert format 1 = Never to 4 = Frequently. Items 4 and 8 have nominal scale responses where the substance consumed most frequently is chosen. Reliability indices (0,82; ω = 0,79). |

|

Condom use Criterion |

The practice of using a latex or other similar material condom during sexual intercourse. The condom acts as a physical barrier between the penis and the vagina, anus or mouth, and aims to prevent unwanted pregnancy and reduce the risk of contracting an STI. |

Consistency index with values between zero and one, which is the result of dividing the number of times the condom is used in six months by the number of sexual intercourses in the same period of time. Values equal to one indicate that the person is consistent in the use of condoms. |

Consistent condom use with two items to assess the number of times they had sexual intercourse and used a condom in the last six months (DiClemente & Wingood, 1995). |

Design

Given the nature of the study, it is based on a quantitative approach with a non-experimental-cross-sectional design with a predictive-explanatory scope (Ato & Vallejo, 2018; Hernández & Mendoza, 2018; Supo, 2012).

Study population

As previously mentioned, the study population consisted of MSM, a group at disproportionately high risk of HIV infection. This population has reported inconsistent condom use during sex, which is associated with various psychosocial factors. It is important to emphasize that the inclusion of the MSM population is essential to address the HIV epidemic and develop effective prevention strategies that consider both aspects of sexual behavior and psychosocial factors. To this end, non-probabilistic convenience sampling was used, ideal for accessing low-incidence or difficult-to-reach populations, using the online sampling method that allows reaching the hidden population, expanding the sample size and the scope of the study and reducing costs and time (Hernández & Carpio, 2019; Hernández & Mendoza, 2018). In the same vein, Baltar and Gorjup (2012) consider virtual sampling to be an effective means of contacting participants from different places, achieving higher response rates, and providing a broad sample with diverse sociodemographic characteristics.

Sample

The following criteria were used for the selection of the sample:

Selection Criteria

· Be a resident of the state of Jalisco

· Identify with the biological sex “man”.

· Be over 18 years of age.

· Have or have had a sexual relationship with one or more men in the last six months.

· Agree to informed consent and participate voluntarily.

Elimination criteria

· Report a positive HIV diagnosis.

· Reporting not having started a sexual life at the time of the study or not having had sexual activity in the last six months with another man.

· Not responding adequately to the battery of instruments.

Various civil society organizations were used to collect the data (Red de Colectivos Diversos de Tepatitlán AC and Mesón AC). The battery of instruments was also disseminated through social networks such as Facebook.

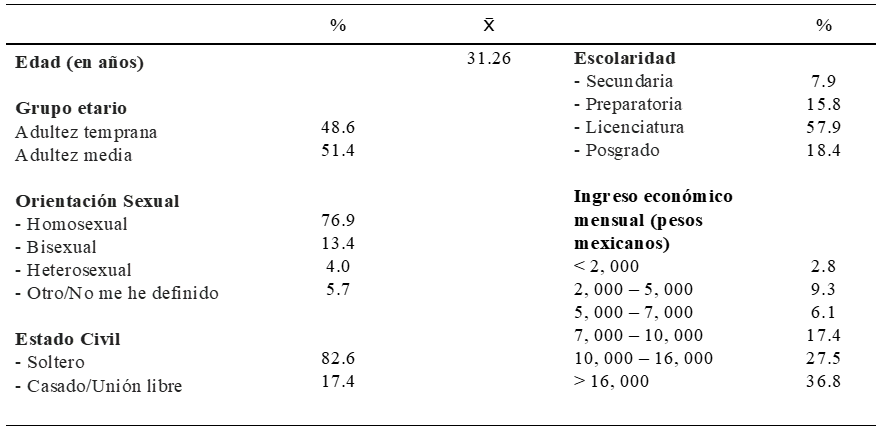

In total, 334 men from different states in Mexico participated. However, 87 of them did not meet the inclusion criteria or were excluded from the database based on the aforementioned elimination criteria, leaving a final sample of 247 MSM in the age range of 18 to 56 years (x̅ = 31,26; DE = 7,528), 76,9 % identified as homosexual, 82,6 % reported being single, 61,9 % had a university education. For the rest of the characteristics, see figure 1.

Figure 1. Characterization of the sociodemographic variables (n = 247)

Characterization of the sexual life variables

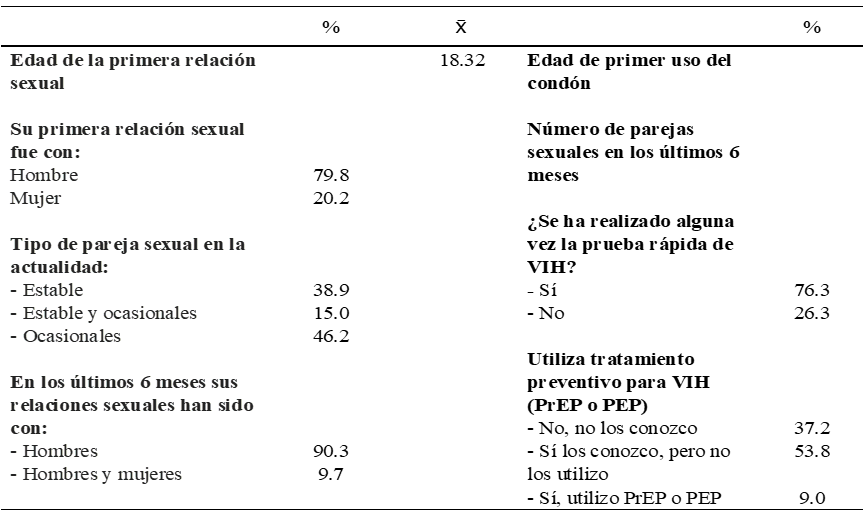

Figure 2 shows the characteristics of the participants' sexual lives, with an average age of onset of sexual activity of 18,32 years (minimum 6; maximum 33) and an average age of onset of condom use of 19,42 years. 46,2 % of participants reported having an occasional sexual partner, with an average of 4 partners in the last six months. Likewise, the majority of individuals mentioned that in the last six months, their sexual relations have been exclusively with men (90,3 %).

Figure 2. Characterization of the sexual life variables (n = 247)

Measuring instruments

Based on the general research approach, a set of instruments was integrated to evaluate the variables of interest. Each of them is described below:

In the first part of the set of tests, informed consent was provided, indicating the objectives of the evaluation, the types of results to be obtained, and the academic and confidential purposes of the study. Similarly, an attempt was made to reduce social desirability by providing participants with detailed and transparent information about the purpose of the study, the procedures that would be carried out, and the possible risks and benefits.

Subsequently, a questionnaire on personal data and sex life was administered to gather information relevant to the study:

· Age.

· Sexual orientation.

· Marital status.

· Education.

· Income.

· Age at first sexual intercourse.

· Age at which the participant started using condoms.

· Type of sexual partners at the time of the study.

· Number of sexual partners in the last six months.

· Knowledge of HIV serological status.

· Use of prophylactic treatment for HIV.

To complete the questionnaire, the participant had to write their answer in the spaces provided for that purpose or tick the corresponding box.

The second part of the set of tests consisted of instruments that assessed protective and risk factors:

Scale of perception of risk of HIV transmission through sex [EPR-VIH] (Sánchez, Lozano, et al. 2021).

A scale of 16 items with five Likert-type response options (1=Strongly disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither agree nor disagree, 4=Agree and 5=Strongly agree) that assess three main factors: risky sexual practices (items 4, 7, 8, 10 and 16), HIV transmission situation (items 2, 5, 11, 13, 14 and 15), and safe sexual practices (items 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12). Overall, the scale has a Cronbach's alpha of 0,78 in the Mexican population, which, according to the authors, is an acceptable reliability index. For the present doctoral study, reliability analyses were carried out using Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega tests, yielding values of α = 0,62 and ω = 0,65, which, according to the literature, require values above 0,70 to be considered acceptable (Medrano & Pérez, 2019).

Therefore, we proceeded to calculate the reliability indices by eliminating items. Both Cronbach's alpha test and McDonald's Omega index suggested that it would be appropriate to eliminate item 5: "It is safe to have unprotected sex with a person who has HIV if the virus is undetectable due to treatment." This item uses technical and complex terms, such as "undetectable," which may not be fully understood by study participants, who may interpret as "cured," which could distort the responses. This confusion may stem from a lack of clarity about what it means to be undetectable in a clinical context and how it relates to the risk of transmission. Once the item was removed from the total scale, improvements were obtained in the reliability indexes (α = 0,71; ω = 0,71).

Sexual assertiveness

To evaluate sexual assertiveness, the Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS) designed by Morokoff et al. (1997), adapted into Spanish by Sierra et al. (2011), and validated in the Mexican population by Torres et al. (2017) was used. It is made up of 18 items, distributed in three components: The first sub-scale (Start of sexual intercourse; items 1-6) assesses the frequency with which a person starts sexual intercourse and whether it happens in a desired way; the second (Refusal of sexual intercourse; items 7-12) measures the frequency with which a person can avoid both sexual intercourse and unwanted sexual activity; the last dimension (STI prevention; items 13-18) evaluates the frequency with which a person insists on using latex barrier contraceptive methods with their partner. All items are scored on a Likert-type response scale between 0 (Never) and 4 (Always). High scores indicate greater sexual assertiveness. As for its reliability, it has yielded Cronbach's alpha values between 0,71 and 0,85, which are considered acceptable. The present doctoral study's reliability analyses were performed using Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega tests, yielding acceptable values (α = 0,81; ω = 0,81).

Sexual Sensation Seeking

The Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale (SSSS-9) by Kalichman et al. (1995), adapted into Spanish and validated in Mexican adults by Moral de la Rubia (2018), consists of nine items with a Likert-type response format, ordered from 1 = Strongly disagree to 4 = Strongly agree. Likewise, the total number of items is distributed in two dimensions: Search for new sexual sensations and Search for new sexual experiences. The total score was obtained by adding the nine items and dividing by nine, giving a continuum from 1 to 4. A higher score reflects a greater tendency to seek sexual arousal, experiences, and novelties. It has an acceptable internal consistency in the Mexican population (Cronbach's α = 0,93) [see Appendix E]. For this doctoral study, reliability analyses were carried out using Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega tests, yielding acceptable values (α = 0,80; ω = 0,81).

Use of psychoactive substances

For the evaluation of psychoactive substance use, the Situational Influences on Sexual Behavior in MSM Questionnaire (ISCS_HSH; Moral de la Rubia et al., 2016), validated in the Mexican population, was used. The questionnaire consists of 14 items that measure the frequency of exposure to situations that may influence the adoption of sexual behaviors that are risky for HIV. Eight items assess the frequency of going to certain places to meet partners, while six items address the frequency of alcohol and drug use before sexual encounters, about the person, the sexual partner, or both. For this study, only the alcohol and drug use subscale was used. The response format is Likert-type, with a range of one to four (1= never, 2= rarely, 3= sometimes, 4= frequently). Higher scores indicate greater exposure to alcohol and drug use. The internal consistency of the items that evaluate substance use is 0,88, which is considered good. This doctoral study conducted reliability analyses using Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega tests, yielding acceptable values (α = 0,82; ω = 0,79).

Consistency in condom use

Based on the proposal by DiClemente and Wingood (1995), used in the same way by Sánchez et al. (2021) in the MSM population, two items were used to assess the number of times they had sex and used a condom in the last six months. From this, a consistency index was obtained with values between zero and one, which is the result of dividing the number of times the condom was used in the last six months by the number of sexual relations in the same period. Values equal to one indicate that the person consistently uses the condom.

Similarly, a Likert-format item was designed to assess the frequency of condom use in their last sexual relations, which was worded as follows: In the previous six months, have you had penetrative sexual relations, either insertive or receptive, using a condom? The answer options range from 0 = Never to 3 = Always. The higher the score, the greater the use of condoms in penetrative sex.

Statistical procedures and analysis

The battery of instruments was transcribed into a digital format using the Google Forms platform so that it could be answered from any device with internet access (laptop, tablet, or cell phone). The literature indicates that, in many fields of research, online surveys can be a powerful tool for improving the scope of studies, maximizing the time-cost ratio, and increasing the size of the sample, especially when working with hidden populations (Baltar & Gorjup, 2012; Hernández & Carpio, 2019).

Once the data collection phase was completed, questionnaires that were not adequately completed were excluded, either because data was omitted or because they showed an unusual pattern of responses that raised doubts about the authenticity of the data provided. The study variables were then coded in a database using Excel 2016.

Statistical analysis

Following on from the above, the necessary statistical analyses were carried out to test the previously drafted hypotheses, using the statistical package SPSS v20 and the software JASP v.17:

· For the analysis of sociodemographic and sexual life data, as well as for the characterization of the variables in the study sample, descriptive statistics, frequency measures and percentages for categorical variables, and measures of central tendency (mean and standard deviations) for numerical variables were used.

· We then proceeded to determine the normal distribution of the study variables by means of the Shapiro-Wilk test, which determined that only the sexual assertiveness variable presented a normal distribution (p = 0,091), while the rest of the variables reported an asymmetric distribution. Therefore, it was decided to use non-parametric tests for the statistical analyses.

· Subsequently, a bivariate analysis with Spearman's Rho was applied, which allowed us to know the degree of relationship between the study variables, taking a significant value of p ≤ 0,05.

· Finally, a binomial logistic regression analysis was applied to evaluate how the predictor variables (perception of HIV risk, sexual assertiveness, seeking of sexual sensations and substance use) were related to the variable to be predicted (use of condoms). This made it possible to determine which variables showed a significant influence and in what direction (Reidl & Guillén, 2019).

Ethical Aspects

The study procedure complies with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, which is based on the basic principle of respect for the individual, their right to self-determination, and their right to make decisions once they have been informed of the risks and benefits of participating or not participating in a study. In this sense, prior to the application of the measuring instruments, the participants were provided with informed consent, which indicated the objective of the study, the minimal risks, and the benefits obtained by participating.

On the other hand, the project adheres to the specifications of the General Health Law of Mexico in terms of research for the health of the Secretary of Health (2014), which establishes that at all times, research for health must address ethical aspects that guarantee the dignity and well-being of the people subject to the research. In accordance with the provisions of Chapter I, Article 13 establishes that in any research involving human beings, respect for their dignity and the protection of their rights and welfare must prevail. Therefore, at all times, participants must be treated with courtesy and respect, and the measuring instruments shall be applied to guarantee anonymity and confidentiality. Concerning Article 14, informed consent has been obtained from a health professional, the author of this doctoral project, with knowledge and experience in caring for the integrity and well-being of human beings. Based on Article 16, the aim is to protect the participants' privacy, as no personal data such as their names will be collected, thus avoiding information that could identify the person, and the research base will be handled solely and exclusively by the researcher of this project. By Article 17, the present investigation is considered to be of minimal risk since only documentary instruments were applied that addressed aspects related to the sexual behavior of the participants. By Article 21, the participants received a clear and complete explanation of the study and its objectives, that there would be no financial benefit for their participation, that the study did not represent any risk to their physical and psychological integrity, that their contribution would be important for the generation of new knowledge, and that they would be free to withdraw from the study without any repercussions. Finally, considering Article 58, the results obtained will be used exclusively for research purposes through their dissemination in scientific journals and events.

This protocol was reviewed and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Aguascalientes [COB-UAA/105/2023].

RESULTS

Considering the specific objective of describing the main study variables in the MSM sample, descriptive analyses were carried out based on the theoretical mean presented below.

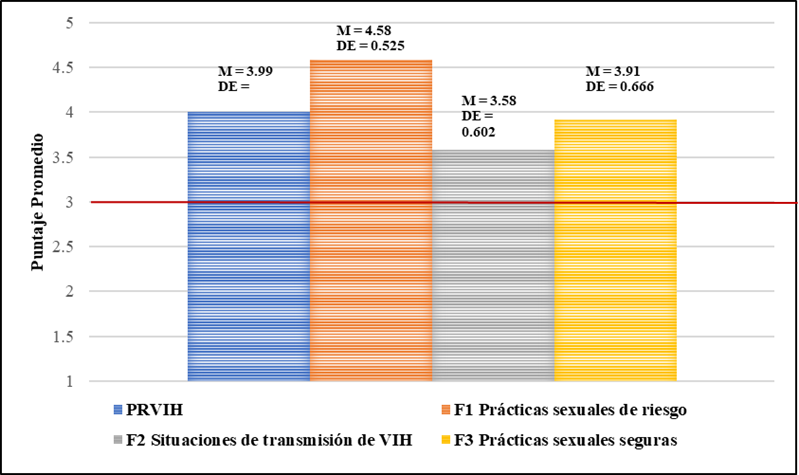

Figure 3 shows the characteristics of the perception of HIV risk; the values obtained both on the total scale and in their respective dimensions indicate moderate-high ranges in general terms, with the dimension F1 Risky Sexual Practices being the one with the highest score above the rest of the components of the scale. It should be noted that the theoretical mean of the scale is 3, so the scores obtained are compared against this value to determine whether or not individuals exhibit the attribute in question. This indicates that MSM evaluate and understand the sexual practices that have the most significant potential to transmit the virus and similarly how they consider certain sexual behaviors as more or less risky in terms of HIV acquisition or transmission.

Figure 3. Descriptive analysis of the HIV Risk Perception Scale (HRPS)

Note: The means (M) and standard deviations (SD) of the HIV risk perception scale and its respective dimensions are shown.

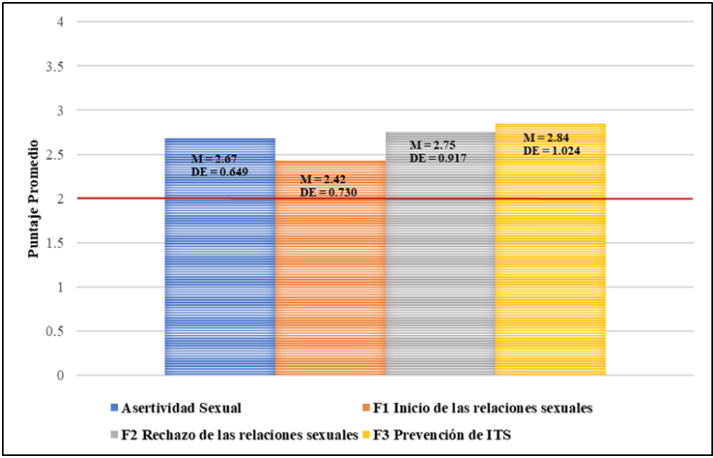

Figure 4 presents the characteristics of sexual assertiveness, which indicates values above the theoretical mean of 2. This suggests that both general sexual assertiveness and its respective dimensions present moderate levels. It should be noted that the F3 STI Prevention dimension shows a slightly higher score compared to the other dimensions, indicating that the sample evaluated tends to communicate their desires, needs, and limits in the context of sexual relations with their sexual partners, to prevent the transmission of HIV and other STIs, and maintaining a healthy and safe sex life.

Figure 4. Descriptive analysis of the Sexual Assertiveness Scale (AS)

Note: The averages (M) and standard deviations (SD) of the Sexual Assertiveness (SA) scale and its respective dimensions are shown.

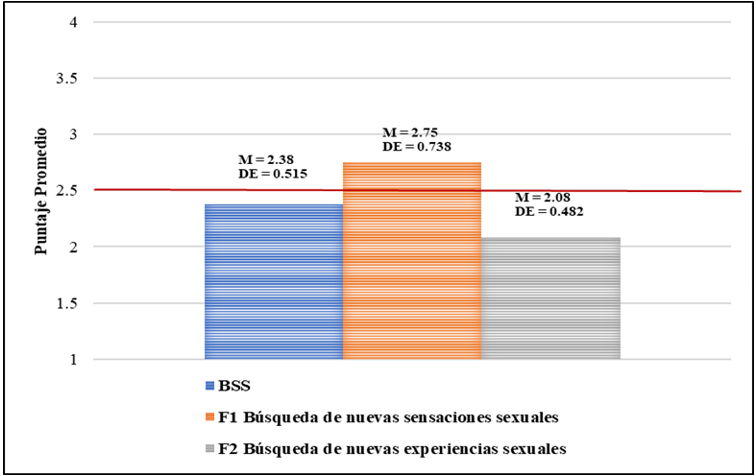

About the search for sexual sensations, figure 5 shows an average of 2,38, which, when compared with the theoretical average of 2,5, indicates a moderate willingness to seek out and participate in novel sexual experiences. The dimension with the highest score is the F1 Search for new sexual sensations, which suggests that the study participants tend to explore different or novel sexual experiences and activities to experience new sensations that produce arousal, pleasure, or sexual satisfaction. In this factor, the contents about sensations without explicit reference to the external predominate.

Figure 5. Descriptive analysis of the Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale (SSSS)

Note: The averages (M) and standard deviations (SD) of the scale of the search for sexual sensations (BSS) and their respective dimensions are shown.

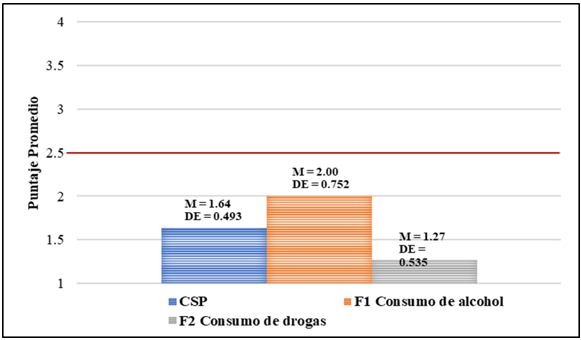

In addition, figure 6 provides a visual representation of the data related to the consumption of psychoactive substances during sexual intercourse. It can be seen that the levels of consumption of these substances are moderately low in comparison with the theoretical average of 2,5, with a more marked tendency towards the consumption of alcohol in comparison with other drugs.

Figure 6. Descriptive analysis of the Psychoactive Substance Consumption Scale (CSP)

Note: The averages (M) and standard deviations (SD) of the scale of consumption of psychoactive substances (CPS) and their respective dimensions are shown.

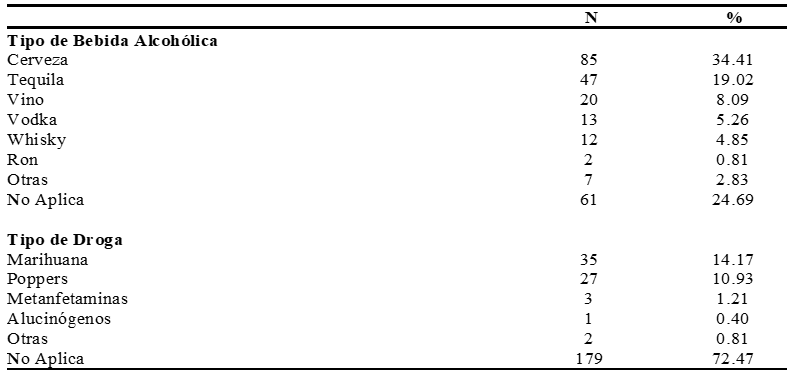

Furthermore, within the variety of alcoholic beverages, beer is the most frequently consumed, while, with regard to the use of other drugs, marijuana stands out for its greater frequency. figure 7 shows the specific percentages.

Figure 7. Frequency of psychoactive substance use according to type (N=247)

Note: The category Not Applicable corresponds to people who reported not consuming any psychoactive substances.

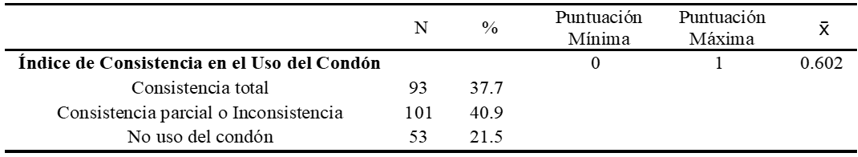

About the consistency index in condom use, figure 8 shows an average score of 0,608 on a scale of 0 to 1, which indicates that those evaluated reported inconsistency in condom use. In this sense, only 37,6 % of the individuals reported total consistency; that is, they always use a condom during all their sexual relations. On the other hand, 40,9 % of those evaluated reported partial consistency, also known as inconsistency, which means that they use condoms on some occasions but not during all sexual relations. Finally, 21,45 % of the participants reported never using condoms during sexual relations.

Figure 8. Descriptive analysis of the variable condom use (n=247)

Results of the Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis

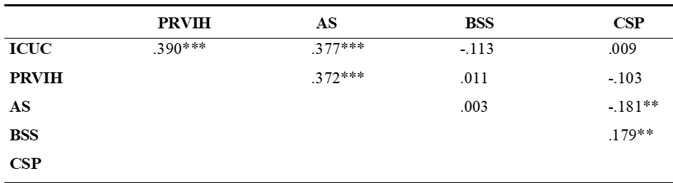

As part of the bivariate analysis, the correlation of the consistency index in condom use with the other study variables was examined. Spearman's Rho correlation test revealed a positive and moderately strong relationship in terms of size and effect with two variables: perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness, suggesting that an increase in these variables is associated with increased condom use. On the other hand, no significant correlation was found between condom use and the search for sexual sensations or the consumption of psychoactive substances, which also did not show an important effect on the consistency of condom use in this sample of MSM. In addition, a statistically significant correlation was identified between some of the independent variables, as shown in figure 9.

Figure 9. Correlation analysis between the study variables

Note: Spearman's Rho Correlation Analysis. (ICUC) Consistent use of condoms; (PRVIH) Perception of HIV risk; (AS) Sexual assertiveness; (BSS) Search for sexual sensations; (CSP) Use of psychoactive substances. *The correlation is significant at the 0,05 level **The correlation is significant at the 0,01 level *** The correlation is significant at the 0,001

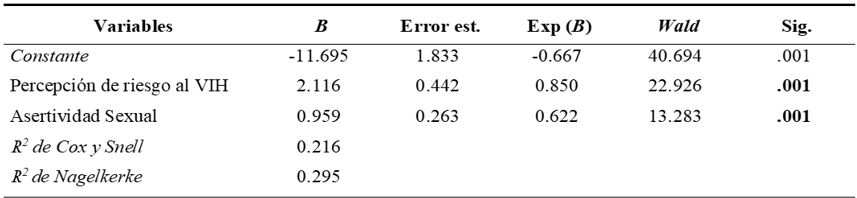

As a final procedure, a binomial logistic regression analysis was carried out. This analysis is used mainly to predict the probability of an event occurring, in this case, consistent condom use.

As a first point, using the codon was considered the dependent variable. The variable's perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness were independent variables, discarding the variable's search for sexual sensations and consumption of psychoactive substances as they did not show a significant relationship with the index of consistency in condom use in the previous analysis. It is important to mention that, for the logistic regression, the variable index of consistency in condom use was dichotomized, considering the scores 0 to 0,99 as "inconsistency in condom use" (62,4 %) and the values equal to 1 as "consistency in condom use" (37,6 %).

Figure 10 shows the values of the regression model, which was statistically significant, X2 (244) = 60,171, p < 0,001, finding positive coefficients, which indicates that condom use increases when the levels of perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness are higher (p < 0,001). On the other hand, the explanatory scope is found between the Cox and Snell, and Nagelkerke values; that is to say, the model explains between 21,6 % and 29,5 % of the total variance.

Figure 10. Binomial logistic regression model for condom use

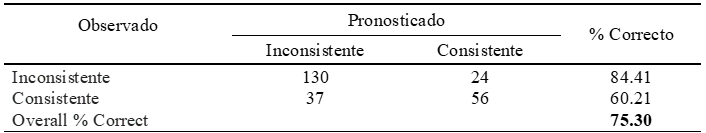

On the other hand, when making a forecast between the observed data and the prediction values, the model performs well, predicting cases of inconsistency in condom use with an accuracy of 84,41 %, while for cases of consistency in condom use, an accuracy of 60,21 % is reported, which is considered moderate performance. The overall accuracy of the model, considering both cases of inconsistency and consistency, is 75,3 % (figure 11).

Figure 11. Matrix of disorder

DISCUSSION

This doctoral thesis starts from the general research question: To what extent do protective psychological factors (perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness) and risk factors (search for sexual sensations and consumption of psychoactive substances) influence condom use in a sample of MSM in the state of Jalisco? Although the literature indicates that there is an inconsistency in the use of condoms during sexual intercourse in the MSM population, scientific evidence has identified a wide range of psychosocial factors associated with this problem, which have been integrated into various explanatory models from Health Psychology. However, other cognitive-behavioral variables, both protective and risk, have not been studied in MSM in the Mexican context nor incorporated into the aforementioned theoretical models.

In this sense, the general objective of this research was to evaluate and explain the influence of protective psychological factors (perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness) and risk factors (search for sexual sensations and consumption of psychoactive substances) on the use of condoms as a preventive measure against HIV in a sample of MSM in the state of Jalisco, Mexico.

Sociodemographic characteristics and sexual behavior

In the sample evaluated (n=247), a higher percentage of people who identified as homosexual was found; this is consistent with what is stated in the literature, which defines homosexual people as those who feel an emotional and/or sexual attraction towards people of the same sex. However, another percentage of the sample evaluated (4 %) reported being heterosexual, assuming that despite feeling attracted to people of the opposite sex, they manage to have sexual interaction with other men. This result coincides with other studies (Bautista et al., 2013). This could be due to the process of exploring sexuality and the search for new sexual experiences and sensations without necessarily feeling sexually oriented towards men (Posada et al., 2018). Similarly, due to the context in which the research was carried out, it is somewhat tricky to publicly assume that one has had sexual relations with other men due to the stigma and social discrimination that they may suffer (Ali et al., 2019).

Regarding the age of initiation of sexual activity, an average of 18,32 years was found. However, it is interesting to note that some participants mentioned having started their sexual activity at ages as young as 6, 8, and 9. This may be due to two possible reasons: 1) an error in recording the age, or 2) that these individuals have been victims of child sexual abuse and consider that experience as the beginning of their sexual life, so it would be worthwhile in future research to ask whether or not the first sexual encounter was consensual. Despite these individual differences, this finding regarding age is in line with other studies that suggest that the average age of initiation of sexual activity in men is usually in late adolescence or early adulthood, generally around 16 to 18 years of age. It is important to emphasize that this age can vary significantly depending on the context and various personal, cultural, and social factors (Martínez et al., 2016; Milanes et al., 2023). Likewise, the participants reported an average age of 19 years for the initiation of condom use in their sexual relations, which indicates that MSM managed to use condoms for the first time very close to their first sexual relationship.

A notable feature in the sample analyzed is that the majority reported having occasional sexual partners, with an average of four partners in the last six months, which has been associated with an increased risk of acquiring HIV. It is important to note that no universal average number applies to all MSM, as this can vary significantly depending on context, culture, age, and other factors. However, some surveys have revealed differences in the average number of sexual partners between MSM and men who have sex exclusively with women (López et al., 2021; Sanabria et al., 2020). It is essential to remember that these averages may not reflect the diversity of sexual experiences and relationships, which is wide and varied.

Furthermore, it is important to mention that the majority of those surveyed reported having undergone an HIV test at some point in their lives. This reflects the importance they attach to early detection and self-care in their sexual health, which is possibly related to a high perception of the risk of acquiring HIV. However, these data differ from what Sanabria et al. (2020) found in a sample of young people, where only 20 % had sought a healthcare center to perform the screening test. This was mainly associated with a low perception of the risk of contracting the infection, trust in sexual partners, and the lack of availability of testing. It would be valuable to examine in greater depth the role that risk perception plays in HIV screening in this MSM population.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that a low percentage (9 %) of the participants in this study indicated that they used pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) as a method of HIV prevention. This fact could be associated with the omission of condoms during sexual relations in this population, as the use of PrEP could make some people feel protected exclusively against HIV, diminishing the perceived need to use barrier methods. PrEP may give people greater personal control over their sexual health, as it only requires one pill a day and removes the need to depend on the partner to use a condom correctly in all sexual situations. For some people, the convenience of PrEP is an important factor, as it does not involve remembering to use a condom at every sexual encounter, which, in turn, improves intimacy and sensitivity during sex. However, it is crucial to bear in mind that PrEP does not protect against other STIs so that condom use can be recommended for comprehensive STI prevention (Ramchandani & Golden, 2019; Tan et al., 2020). The relationship between PrEP use and condom omission is an aspect that could be addressed in future research, as it raises important questions about risk perception and the adoption of preventive behaviors in MSM populations.

Characterization of protective and risk psychological factors and condom use

Firstly, about the variable of perception of HIV risk, the MSM evaluated reported moderate to high scores. This finding suggests that, in general, MSM are aware of the risks associated with HIV, which is a positive aspect in terms of prevention and decision-making regarding their sexual health. A moderate to high perception of the risk of contracting HIV can have several important implications, including a greater likelihood of adopting preventive behaviors, such as condom use (Pérez et al., 2016) and regular HIV testing (Acosta, 2021; Dacus & Sandfort, 2020). In this sense, risk awareness can motivate individuals to be more cautious and to take active measures to protect themselves and their sexual partners.

However, it is important to consider some factors influencing this perception of risk, such as education. The majority of those evaluated reported having a bachelor's degree. Access to accurate and up-to-date information about HIV plays a crucial role. MSM with better access to educational resources and sexual health services may develop a more realistic and adequate perception of their risk of contracting HIV. In addition, information and education play an important role, as access to information about HIV through the media, the internet, health professionals, or personal experiences can influence the perception of risk. Another aspect to be highlighted is that some men are aware of their high-risk sexual practices when they have multiple sexual partners whose HIV status they do not know, which can generate anxiety and excessive fear, leading to an increased perception of HIV risk.

Even though the findings report moderate to high levels of perceived HIV risk, these data differ from what has been reported by other studies, in which between 75 % and 90 % of participants experience invulnerability to HIV, regardless of their actual sexual behaviors (Guerra et al., 2022; Lameiras et al., 2002; Pastor & Rojas, 2019; Saura et al., 2019; Torres et al., 2018). These authors consider that this phenomenon is attributed to various factors, including the perception of low personal vulnerability, unrealistic optimism, and an underestimation of one's own risk in contrast to an overestimation of the risk to others. It is important to bear in mind that the perception of risk can vary widely between individuals and groups and does not always correlate directly with the real risk of acquiring HIV. The perception of risk is an important factor in decision-making among MSM, but it must be backed up by accurate information and effective prevention practices (Guerra et al., 2022; Torres et al., 2018).

Although the scores for the perception of HIV risk among the MSM evaluated in this study, ranging from moderate to high, are indicative of significant risk awareness, it is necessary to optimize the results in terms of prevention and well-being, which would allow for the implementation of educational strategies aimed at this key population.

About the sexual assertiveness variable, it was observed that the MSM evaluated in this study reported scores in the moderate to low range. This finding raises questions about the reasons underlying these levels of sexual assertiveness, considering that sexual assertiveness implies a person's ability to communicate their sexual desires, limits, and needs clearly and directly, both in the context prior to and during a sexual relationship. In this sense, a lower capacity to negotiate and communicate desires and limits in sexual situations can lead to non-consensual sexual encounters, where there is no comfort in expressing one's desires, including the use of condoms.

On the other hand, Santos and Sierra (2010) state that sexual assertiveness is a fundamental component of human sexuality, relating to aspects such as sexual satisfaction. They emphasize that low levels of sexual assertiveness can negatively impact sexual satisfaction, leading to less pleasure and enjoyment during sexual intercourse.

One possible explanation for the observed levels could be associated with the type of sexual partners these men have, mostly casual partners, which could make assertive communication difficult during sexual encounters with strangers. Furthermore, low sexual assertiveness with casual partners could be related to the processes of social stigma and discrimination that many MSM face, inhibiting their ability to communicate with others. It is therefore advisable to develop inclusive sex education programs and public policies that protect sexual minorities, promoting an environment where MSM can develop their sexual assertiveness safely and healthily.

Although the results reported here indicate a tendency towards low and moderate assertiveness, these differ from previous research in young MSM populations, as evidenced in the studies by Morell et al. (2021) and Osorio et al. (2017). These studies have reported high levels of sexual assertiveness and have suggested that this skill is a protective factor in negotiating condom use before engaging in sexual relations with other people. Given this discrepancy in the results, it would be valuable to replicate this type of study in a larger sample to compare and analyze similar research results and consider strategies and approaches that can counteract possible hegemonic masculine norms that promote sexual risk-taking. This would allow for a more complete understanding of sexual assertiveness in the MSM population and could have significant implications for the promotion of safe sex practices and HIV prevention.

About the search for sexual sensations, the subjects evaluated report moderate levels of risk. These findings could be associated with motivational processes and vary according to culture, education, previous experiences, and individual circumstances. Other possible reasons for this risk factor in MSM could be the natural curiosity to explore what they like and what gives them satisfaction, the desire to avoid monotony and routine in their intimate life, the process of discovering their sexual identity, the search for personal satisfaction and the improvement of intimacy with a partner. In other cases, it could be due to the search for sexual stimulation and arousal, which allows them to strengthen the emotional and physical connection in their relationships.

In this sense, these data are consistent with other studies that have revealed that men who are highly prone to seeking new sensations have a significant capacity to take risks, which leads them to act impulsively, even in situations in which they are under the influence of psychoactive substances (González et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2016). Likewise, an evident connection has been identified between sensation seeking and participation in high-risk sexual behaviors, such as the reluctance to use condoms and the involvement in sexual encounters with unknown individuals, with marked levels of scoring in this dimension and a clear correlation between these factors (Wang et al., 2021). It has also been found that the propensity to seek sensations also plays a significant role in the involvement in sexual relations during the consumption of psychoactive substances.

Regarding the consumption of psychoactive substances, it can be seen that the degree of consumption prior to sexual relations is moderately low. Despite this, of the total sample evaluated, 82,2 % reported having consumed some substance at some point in their life before initiating sexual relations with their partner, whether stable or occasional. Among the most frequent substances were alcohol and marijuana. These data are consistent with other studies conducted on the MSM population, where it was found that the consumption of drugs for sexual purposes is prevalent among men who have sex with other men, reaching 21,9 % in the last 12 months before their sexual encounters. The most commonly reported patterns of use include recreational drugs, substances to enhance sexual performance, and "chem sex" (Guerras et al., 2022). An interesting fact mentioned by these authors is that substance use patterns were more frequent in MSM who already had a positive HIV diagnosis, indicating an increased risk of transmitting the virus to their sexual partners, mainly if condoms are not used.

On the other hand, Hibbert et al. (2019) confirmed that recreational drug use is associated with a higher sexual risk, which implies a more significant number of sexual partners. Even though the MSM evaluated expressed satisfaction with their risk behaviors, the need for social support for these vulnerable groups is raised. Similarly, a study carried out in Mexico reported that 66,3 % of the MSM who participated in the evaluation reported having consumed alcohol and other drugs during their sexual relations, highlighting marijuana, cocaine, and poppers as the most frequently used drugs. In this process, a direct association was identified with internalized homophobia in the subjects evaluated, which suggests that the substance use problems presented by MSM may be a consequence of stigma and social discrimination (Hernández et al., 2017). In general, it is advisable to expand the studies to different regions and cultural contexts to assess whether consumption patterns and associated factors vary, which could provide valuable information for implementing specific prevention programs at the local level.

Finally, when assessing consistency in condom use, it was found that only 37,6 % consistently use condoms during sex, while 21,45 % report not using them at all, and the rest use them inconsistently. This finding has significant implications for the sexual health of MSM in Mexico. It raises several questions about the possible factors that could be influencing these practices, which, according to the literature review, could be the perception of invulnerability to HIV accompanied by unrealistic optimism and the underestimation of personal risk (Pérez et al., 2016; Pastor & Rojas, 2019; Sánchez, Lozano, et al., 2021; Torres et al., 2018); on the other hand, the stigma surrounding HIV and the sexual practices of MSM can negatively affect condom use, triggering a fear of discrimination and marginalization that can discourage individuals from carrying condoms or negotiating them with their sexual partners, particularly in contexts where conservative ideologies towards sexual minorities are more prevalent (Mendoza & Ortiz, 2009; Restrepo & Villegas, 2023).

These data are similar to what has been found in other studies where it has been observed that a significant proportion of MSM in Mexico still engage in sexual practices associated with HIV infection, such as in the case of Mendoza and Ortiz (2009) who evaluated MSM in Ciudad Juárez, finding that inconsistent condom use was 33,1 % in receptive anal sex and 33,9 % in insertive anal sex, in addition to the fact that the majority reported inconsistent condom use in receptive (87,6 %) and insertive (86,7 %) oral sex. On the other hand, some studies indicate that between 50 % and 80 % of MSM do not use condoms (Hentges et al., 2023; Milans et al., 2023) associated with sociocultural factors, such as the lack of sex education, the beliefs and ideologies of the context in which they operate, the lack of access to the health system, the lack of communication with their partner or, in some cases, their own decisions. It is important to emphasize that inconsistent condom use increases the risk of HIV infection, which has led to the classification of MSM as a key population for the development of the disease. However, the statement that MSM does not use condoms during sex can lead to a stereotype that does not reflect reality. While it is true that some people may take risks during sex, it is important not to stigmatize a particular group.

Relationship between the study variables

In addition to the frequency of condom use among MSM in Jalisco, the doctoral thesis work made it possible to identify some factors associated with condom use. To this end, we now consider the correlation analyses between the key variables of the study: the perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness (as protective factors) and the search for sexual sensations and the consumption of psychoactive substances (as risk factors) with consistency in the use of condoms. The main objective of this analysis was to determine if there is a significant relationship between these variables and, if so, to evaluate the nature and strength of this association.

Firstly, a positive correlation of moderate to low intensity was identified between the perception of the risk of acquiring HIV and sexual assertiveness about condom use. This suggests that as the perception of risk and the capacity for assertive communication on sexual matters increase, so does consistency in condom use. These findings can be explained by the fact that greater vulnerability to HIV can awaken a greater awareness of the need for protection in sexual relations, which encourages a proactive attitude towards the prevention of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, with the use of condoms as a protective measure. Furthermore, sexual assertiveness can involve the ability to communicate effectively with one's partner about the importance of condom use, which facilitates its implementation in sexual relations.

Similarly, a positive correlation was found between perceived HIV risk and sexual assertiveness. Although this relationship was significant but not very high, these variables may be interconnected in multiple ways. For example, a more excellent perception of HIV risk can increase awareness of the need to protect oneself during sexual intercourse, which, in turn, encourages effective communication with one's partner about condom use and other prevention measures that are related to sexual assertiveness. Furthermore, this perception of risk can strengthen the need to have safe sex, which in turn promotes sexual assertiveness by expressing and defending the importance of using condoms during sex. In addition, self-esteem and self-confidence can be linked to the perception of HIV risk, promoting sexual assertiveness by talking openly about protection in intimate relationships, regardless of whether the partner is a steady or casual one. These interactions between perceived HIV risk and sexual assertiveness can contribute to the promotion of safer sexual attitudes and behaviors in men who have sex with men.

These findings coincide with previous studies that have established a direct relationship between the perception of HIV risk and behavioral factors, such as condom use and a low probability of sexual self-care in men who have sex with men (MSM) (Guerra et al., 2022; Sanabria et al., 2020). In addition, a significant association has been found between sexual assertiveness and condom use in this population, with self-efficacy playing a mediating role. The literature indicates that self-efficacy is crucial in adopting preventive behaviors, including sexual assertiveness and condom use (Morell et al., 2021; Nesoff et al., 2016; Uribe et al., 2017). This implies that those who have greater confidence in their ability to negotiate safe sex are also more likely to use condoms consistently. Likewise, Corrales et al. (2022) argue that both sexual assertiveness and self-efficacy are fundamental to developing the necessary skills that prevent risky sexual behavior in key populations, which have generated various health problems in recent years.

About the search for sexual sensations and the consumption of psychoactive substances, no correlations were found with the variable of condom use. This is interesting, as the most recent literature has pointed to these factors as possible risks directly related to inconsistent condom use during sexual intercourse, both in the general population and in MSM (Enstad et al., 2019; Hernández et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2022; Leonangeli et al., 2019; Morell et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). However, a low-intensity negative correlation was identified between the first factor of the sexual sensation-seeking scale (F2 - Search for new sexual experiences) and consistency in condom use (r = -0,190; p = 0,01). This finding could suggest that the participants incline to experiment with a variety of sexual practices or situations that provide them with novelty, excitement or arousal, including the exploration of sexual fantasies, the use of sex toys, and participation in unconventional practices such as encounters with different partners in unusual places, sometimes under the influence of psychoactive substances, which could lead to the omission of condom use during sex. This last piece of data coincides with the approaches of Morell et al. (2021), who conclude that men who use condoms inconsistently exhibit higher levels of new sexual experiences, considering it a risk factor.

In line with the above, another bivariate analysis revealed a statistically significant correlation between the search for sexual sensations and the consumption of psychoactive substances. Although this relationship proved to be weak, it could be explained by the fact that MSM who seek sexual sensations often look for substances that can provide them with a feeling of euphoria, disinhibition, and greater expression of sexuality, which adds to sexual arousal. It is important to bear in mind that some psychoactive substances can increase libido and the willingness to engage in sexual activities, which can encourage people to seek sexual sensations more actively, including some risky practices.

Considering both protective and risk factors in condom use offers several important advantages for research in health psychology. Firstly, it provides a more complete and balanced view of behavior related to condom use. This makes it possible to identify the barriers that prevent its use among MSM and the motivations and facilitators that promote its adoption. A comprehensive view is crucial to understanding behavior, not just from a partial perspective. In addition, including both factors broadens scientific knowledge in psychology, public health, and HIV prevention. This provides a detailed analysis of how risk and protective factors interact, contributing to the existing literature and serving as a basis for future research.

Based on the above, a logistic regression analysis was developed, in which statistically significant values were shown. This finding suggests that the model is adequate to explain the relationship of protective factors with condom use in MSM in Jalisco. In this sense, the positive coefficients found indicate that condom use increases when the levels of perceived risk of HIV and sexual assertiveness are higher. This result is consistent with the theory, which emphasizes the importance of these protective factors in adopting preventive behaviors. (Morell et al., 2021).

As part of these findings, the perception of HIV risk is presented as a crucial predictor of condom use during sex among MSM; this means that those men who perceive a greater risk of contracting HIV are more likely to adopt prevention measures. Likewise, sexual assertiveness is also identified as a significant factor in increasing condom use. This means that, as the literature shows, the ability of MSM to communicate their sexual desires and limits clearly and effectively facilitates the negotiation of condom use with their sexual partners. Although the percentages of the logistic regression indicate that a substantial part of the variance in condom use is explained by the variables of perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness, they also suggest that other factors not included in the model could be influencing this behavior.

The findings obtained in the regression analysis partially coincide with research carried out in other contexts. In particular, it has been found that sexual assertiveness is a protective factor for condom use, which coincides with the results of this study. Furthermore, the perception of HIV risk influences a risk factor for inconsistent condom use since those men who had a lower perception of vulnerability tended to decrease their use of condoms (Morell et al., 2021). However, there are some discrepancies between the results of this study and the findings of other research, especially about the factor of perceived HIV risk. This variation may be due to significant differences between cultural contexts; for example, in the study by Morell et al. (2021) conducted in Spain, a crucial factor could be schooling, given that nearly 60 % of those evaluated reported having a high level of education. This translated into a lower perception of risk and a more significant inconsistency in the use of preventive methods. In contrast, in some regions of Mexico, sex education is less accessible and more limited, which could result in a greater susceptibility to disease due to the lack of adequate information and preventive resources.

However, among the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample in this study, it was reported that the majority also had undergraduate and postgraduate education, reporting moderate to high levels of risk perception, which was associated with condom use. This suggests that the perception of HIV risk does not depend solely on education but is a complex variable influenced by various contextual factors.

That is to say, both a good level of schooling and the lack of it can have paradoxical effects on risk perception and behavior. In contexts with a high level of schooling, there may be a lower perception of HIV risk due to confidence in information and preventive measures. However, this confidence can lead to a false sense of security and less consistent condom use. On the other hand, in contexts with low levels of schooling, the lack of information can increase the perception of HIV risk and, in some cases, encourage more cautious behavior. However, it can also lead to high-risk behavior due to myths and misinformation.

These findings highlight the importance of considering cultural and educational contexts when assessing risk perception and HIV-related preventive behaviors in MSM populations. The contribution of this study lies in underlining the need for specific and contextualized approaches to HIV education and prevention, adapted to the realities of each vulnerable group.

The results of this study allow us to conclude that the perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness are significant protective factors in the adoption of preventive behaviors, such as condom use. This is consistent with previous theories that underline the relevance of these factors in the promotion of sexual health. For example, the theory of Reasoned Action by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) highlights the importance of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control over behavior in predicting intention and actual behavior. These findings reinforce the theory by demonstrating that the perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness (perceived control) influence condom use.

Limitations

Although the study reported findings relevant to health psychology and HIV in vulnerable contexts, it is important to recognize that the limitations are not limited to technical or methodological factors.

Firstly, uncontrolled variables in the study, such as the influence of psychosocial and contextual factors, could have affected perceptions and behaviors related to condom use. Aspects such as religious beliefs, access to comprehensive sex education, the availability of preventive resources (such as prophylactic treatment, PrEP), and social support operate at very diverse and complex levels. Their impact on sexual protection attitudes and behaviors can vary considerably between individuals, causing the results not to reflect a homogeneous pattern throughout the sample.

Furthermore, factors such as risk perception and sexual assertiveness are deeply intertwined with personal experiences, partner relationships, and the power dynamics in sexual interactions. These elements, difficult to capture accurately in quantitative studies, add a layer of complexity that limits the conclusions that can be drawn. The stigma associated with HIV and sexual identity is also a critical contextual variable that qualitatively affects sexual protection decisions, which could explain variations in condom use that go beyond what traditional quantitative models can capture.

In terms of methodological limitations, the sample size was small, with only 247 men included who reported having had sex with other men in the last six months. While significant correlations were identified between the variables studied, a larger sample size would have allowed for greater statistical precision and a more remarkable ability to detect subtle effects between variables. This would also have improved the generalization of the results to the broader MSM population. However, this should not be interpreted as a design error but rather as an inherent characteristic of studies that work with specific and often difficult-to-access populations, as with MSM.

The use of non-probabilistic sampling techniques, such as convenience or snowball sampling, may have introduced selection biases, limiting the sample's representativeness and, therefore, the generalization of the findings to the MSM population in Jalisco. However, these methods are standard and often necessary in research that studies marginalized populations or populations that face barriers to participating in studies. This limitation, therefore, is not a defect in the study per se but a consequence of the logistical and ethical restrictions inherent in this type of research. The implementation of additional qualitative studies could help to capture a greater diversity of experiences and enrich the understanding of the factors that influence the sexual behavior of MSM.

Finally, it is important to consider that the results reflect a local reality specific to MSM in the state of Jalisco in Mexico and are not likely to be generalizable to other populations or contexts without making the necessary adaptations. Cultural, social, and political differences between regions can significantly influence perceptions and behaviors related to condom use and other aspects of sexual health. These limitations should not be understood as a flaw in the study but rather as an opportunity for future work to explore these variables in different contexts.

CONCLUSIONS

Starting from the general research objective

To evaluate the influence of protective psychological factors (perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness) and risk factors (search for sexual sensations and consumption of psychoactive substances) on the use of condoms as a preventive measure against HIV in a sample of MSM in the state of Jalisco, Mexico.

The following conclusions are drawn, taking into account the most relevant findings of the study:

1. It is concluded that the MSM evaluated residents of the state of Jalisco, Mexico, do not present consistency in the use of condoms, finding that only a tiny percentage of them manage to meet that criterion to cover a complete and safe sexuality free of risk of HIV infection.

2. The MSM evaluated reported moderate to high scores in terms of their perception of HIV risk. This may be related to awareness of high-risk sexual practices, multiple sexual partners, and personal concerns. HIV information and education may also influence this perception. This contrasts with previous research in which a large proportion of participants experienced a sense of invulnerability to HIV.

3. It was found that the MSM evaluated reported moderate levels of sexual assertiveness. This raises questions about the reasons behind these levels. Although some previous studies had reported higher levels of sexual assertiveness in MSM, this study found a discrepancy. It is suggested that the characteristics of sexual partners, such as having casual partners, can make it challenging to communicate assertively during sex.

4. The subjects evaluated reported moderate levels of sexual sensation seeking. This may be related to curiosity, the desire to avoid monotony, the process of discovering sexual identity, and the search for personal satisfaction. It may also be related to the impulse to seek sexual stimulation and arousal.

5. Although the degree of consumption prior to sexual intercourse was moderately low in this sample, it was found that a significant percentage of MSM had consumed substances before sexual intercourse. Alcohol and marijuana were the most common substances. An association was observed between substance use and the search for sexual sensations.

6. The perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness is positively related to consistent condom use, while the search for new sexual experiences is negatively correlated with this consistency. The lack of a significant correlation between the search for sexual sensations and the consumption of psychoactive substances indicates that these variables may not be determining factors in the consistency of condom use in this specific context.

7. Taking into account the development of the model, the protective factors perception of HIV risk and sexual assertiveness are the variables that directly influence condom use among MSM in Jalisco, explaining between 21,6 % and 29,5 % of the total variance.

8. It is important to consider protective factors in existing models for the design and implementation of educational programs that promote condom use among MSM. These findings have important implications for public health policy and underscore the need for specific and contextualized approaches to HIV education and prevention.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Although the findings of the study provide a significant understanding of the relationship between protective factors and condom use and offer important theoretical and practical implications, it is essential to recognize that in this case, the risk factors analyzed in the model were not significant, and therefore do not explain the observed variance. This suggests that a quantitative approach cannot fully capture some elements of MSM. In this sense, qualitative research could complement these results and provide a deeper understanding of couple dynamics, cultural influences, and perceived barriers to condom use. In-depth interviews or focus groups would be helpful to explore these aspects in detail and enrich the current findings, which can guide future interventions in psychology and sexual health. However, qualitative health research also has limitations in this area, highlighting the need to advance in generating knowledge using these methodologies. So far, they have been less understood by the health sector, but their incorporation could offer valuable perspectives that complement quantitative studies.

On another note, although current research addresses protective and risk factors for condom use in MSM, it is essential to recognize that there are cognitive, behavioral, and affective variables that have not been sufficiently explored and that could significantly enrich our understanding of the subject. According to Morell et al. (2021), by integrating these constructs into the development of explanatory and predictive models, it would be possible not only to increase the accuracy of evaluations but also to identify the underlying mechanisms that influence the sexual behavior of this population. This comprehensive perspective would allow researchers and health professionals to design more effective interventions tailored to the specific needs of MSM, thus promoting safer practices and reducing the incidence of HIV and other STIs. In short, a broader understanding of the determinants of condom use would not only contribute to the academic literature. However, it would also have significant practical implications for public health.