doi: 10.56294/mw2024482

ORIGINAL

Intellectual Quotient and Cognitive Indices in children with and without ADHD in the city of Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco

Coeficiente Intelectual e Índices Cognoscitivos en niños con y sin TDAH de la Ciudad de Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco

José Luis Tornel Avelar1 ![]() *,

Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá1

*,

Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá1

1Universidad De Guadalajara, Maestría En Ciencias Biomédicas. Jalisco, México.

Cite as: Tornel Avelar JL, Cruz Alcalá LE. Intellectual Quotient and Cognitive Indices in children with and without ADHD in the city of Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2024; 3:482. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw2024482

Submitted: 01-10-2023 Revised: 21-02-2024 Accepted: 07-05-2024 Published: 08-05-2024

Editor: PhD.

Prof. Estela Morales Peralta ![]()

Corresponding Author: José Luis Tornel Avelar *

ABSTRACT

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that is between 5 and 8 % of the child population. It was classified clinically by the presence of attention deficit, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Recent research will indicate the presence and the increase in time in school activities in the region of Los Altos de Jalisco, which points to the need to obtain a precise cognitive profile in this regard. With the previous objective, we describe the results of the Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV), applied to children with ADHD and children without the disorder, including the range of 6-11 years of age, in a population total of 89 children, 44 with ADHD (49,4 %) and 45 without ADHD (50,6 %), of these, 62 (69,66 %) correspond to the male sex and 27 (30,33 %) are female, using statistical analyzes Levene for equality of variances, test for equality of means and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (p). The results are not shown. The results are differentiated between the Work Memory Index (IMT), Perceptual Reasoning (IRP), Verbal Comprehension (ICV) and the Total Intellectual Coefficient (CIT). However, if it occurred (0,036 T <0,05). This result is significant to characterize the ADHD group with a cognitive level with a higher IVP score, unlike the group without ADHD. However, a significant index of the same index (IVP) was also identified in the correlation in the increase in age (closer to 11 years of the 6-11 range) in subjects with ADHD (0,006 p <0,01), which is an important finding to identify a cognitive profile of the disorder in the region.

Keywords: Infant ADHD; Cognitive Profile; Iqs; Cognitive Indexes.

RESUMEN

El déficit de atención con hiperactividad (TDAH) es un trastorno del neurodesarrollo que afecta entre el 5 y 8 % de la población infantil. Se caracteriza clínicamente por la presencia de déficit atencional, hiperactividad e impulsividad. Investigaciones recientes señalaron la presencia e incremento del trastorno en escolares de la región de los Altos de Jalisco, lo que apunta a la necesidad de obtener un perfil cognoscitivo preciso al respecto. Con el objetivo previo, se describen los resultados de la Escala de Inteligencia Wechsler para Niños, Cuarta Edición (WISC-IV), aplicada a niños con TDAH y niños sin el trastorno, comprendiendo el rango de 6-11 años de edad, en una población total de 89 niños, 44 con TDAH (49,4 %) y 45 sin TDAH (50,6 %), de los mismos, 62 (69,66 %) corresponden al sexo masculino y 27 (30,33 %) son del sexo femenino, utilizando los análisis estadísticos de Levene para la igualdad de varianzas, prueba T para la igualdad de medias y el Coeficiente de correlación de Pearson (p). Los resultados obtenidos no muestran resultados con diferencias significativas entre los índices de Memoria de Trabajo (IMT), Razonamiento Perceptual (IRP), Comprensión Verbal (ICV) y el Coeficiente Intelectual Total (CIT). Sin embargo, respecto a la distancia entre el Índice Velocidad de Procesamiento (IVP) si se presentó (0,036 T < 0,05). Este resultado es significativo para caracterizar al grupo de TDAH con un nivel cognitivo con una mayor puntuación en IVP a diferencia del grupo sin TDAH. No obstante, a pesar de este resultado, también se identificó un atraso significativo del mismo índice (IVP) en correlación al incremento de la edad (más cercano a los 11 años del rango 6-11) en los sujetos con TDAH (0,006 p < 0,01), lo que es un hallazgo importante para identificar un perfil cognitivo del trastorno en la región.

Palabras clave: TDAH Infantil; Perfil Cognitivo; C.I.; Índices Cognoscitivos.

INTRODUCTION

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neuropsychiatric condition that affects childhood and can persist into adolescence and adulthood. Difficulties in attention, impulsivity, and, in some cases, hyperactivity characterize it. Its impact on children's cognitive and academic development has been widely studied, leading to the implementation of various methodologies to understand its effects on intellectual performance better. In this context, the present study focuses on the evaluation of the cognitive profiles of children diagnosed with ADHD in comparison with those without the disorder, using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV).

The research aims to describe and analyze the significant differences in the cognitive profiles between the two groups using a quantitative approach based on the application of standardized tests. The WISC-IV, a widely validated tool for the assessment of child intelligence, allows the measurement of different aspects of cognitive functioning, including Verbal Comprehension (VCI), Perceptual Reasoning (PRI), Working Memory (WMI), and Processing Speed (PSI), in addition to the Total Intelligence Quotient (TIQ). These indexes offer a comprehensive view of children's cognitive capacities, which facilitates the identification of distinctive patterns in those with ADHD.

The study was carried out with a sample of 89 children aged between 6 and 11, selected from a general database of children evaluated and diagnosed within the framework of the research project on Risk Factors of ADHD in children from Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco. Two groups were formed: 44 children diagnosed with ADHD and 45 children without the disorder. The methodology used was descriptive and comparative, with a cross-sectional design identifying significant differences between the groups in the various cognitive indices.

This study is distinguished by its focus on the Mexican child population, thus contributing to understanding ADHD in a specific context and providing valuable information for educational and clinical intervention. The standardization of the WISC-IV in Mexico supports the validity and reliability of the results obtained. Likewise, it is recognized that, although the analyzed sample is relatively small, the findings can provide relevant knowledge about the impact of ADHD on cognitive development and facilitate support strategies for children with this diagnosis.

Objective

The main objective of the research is to describe any significant differences (0,05) in the WISC-IV test, comparing the evaluations of children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and children without the disorder, both primary school groups from the city of Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco, obtaining a more precise cognitive profile of ADHD in the region.

What differences are there in the IQ and cognitive indices between children diagnosed with ADHD and those without the disorder in Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco?

METHOD

The present study describes the significant differences determined through a quantitative approach, which consisted of analyzing reliable data on the cognitive profiles of both contrast groups, due to the WISC-IV, which is a validated and standardized measurement instrument for the Mexican population.

The Research Ethics Committee of the University Center of Los Altos University of Guadalajara approved the study. Before diagnosis, parents or legal guardians signed an informed consent (Annex 1) by analyzing Risk Factors for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in children in Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco. The study was explained to them, and they agreed to participate while maintaining complete anonymity and using results for publication for academic purposes.

Type of research: This is a descriptive and comparative study. A cross-sectional study was used between two diagnostic groups of primary school students from the city of Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco: one group diagnosed with attention deficit disorder (ADHD) and a second group without the Disorder.

The comparative description will be of the results obtained in the intelligence test that was applied to them.

The IQ of the subjects of the analysis was measured using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Fourth Edition (WISC-IV). The different indexes on the scale were analyzed to obtain the following composite scores: Total Intelligence Quotient (TIQ), Verbal Comprehension (VCI), Perceptual Reasoning (PRI), Working Memory (WMI), and Processing Speed (PSI).

Population: From the general database of children evaluated and diagnosed for the research project on Risk Factors for Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder in children in the city of Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco, led by Dr. Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá, out of a total population of 180 children, 89 boys and girls who met the criteria for the study were selected.

SAMPLE: The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) was applied to 180 children between 6 and 11 years of age enrolled in public and private educational institutions in the city of Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco. Only 44 previously diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder and 45 who did not present the Disorder participated in this study.

Selection Criteria

Approximately 50 % of the subjects had to present a diagnosis of ADHD as established in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Revised (DSM-IV-TR); the other 50 % did not present it, this being endorsed by a medical and psychological diagnostic protocol.

Both groups belonged to an age range between 6 and 11 years old, as well as studying in educational institutions and, those who were given the WISC-IV presented informed consent approved and signed by the father, mother, or legal guardian for statistical and research use.

Exclusion Criteria

The subject's Total Intelligence Quotient (TIQ) must not be evaluated below 70, which is interpreted as a very low IQ; based on the average, it can be associated with an Intellectual Disability or an Intellectual Developmental Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), or above 130, which indicates a result well above the average range. A CIT greater than or equal to 2 SDs above the standardized normative mean of cognitive ability is usually associated with identifying gifted children (The Psychological Corporation, 2003; Winner, 1997, 2000 cited in Flanagan & Kaufman, 2012). Failure to present informed consent approved and signed by the parent or legal guardian for statistical use in research.

Scope and Design

A descriptive-comparative design was carried out between two groups (ADHD and subjects without ADHD) for the analysis of the information (significant differences [0,05]) existing in the results obtained in the WISC-IV test applied to children with ADHD and to children without the Disorder, where their Intelligence Quotient and indices of Verbal Comprehension, Perceptual Reasoning, Working Memory and Processing Speed were evaluated, according to sex and in the range of 6-11 years of age. The cognitive profiles, derived from the research on “Risk Factors for Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder in children in the city of Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco,” were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics Standard, version 24.0.0.0, according to the hypothetical construct of the study.

It is recognized that such a small study group generates a limitation in terms of population representativeness; however, for the purposes of this comparison work, it is not considered inadequate.

Instrument

The interpretation of the results contained in this report is based on the method proposed by Flanagan and Kaufman (2012) in the book Keys to Assessment with the WISC-IV 2nd Edition.

The WISC-IV was developed to provide a general measure of cognitive ability. It consists of a battery of individually administered cognitive tests that measure the intellectual ability of children aged 6 to 16. Although the full version of the WISC-IV has 15 subtests, only 10 are considered core and are used more often. These are combined to obtain four composite scores representing intellectual functioning in specific cognitive domains, called cognitive functioning indices, in addition to a measure of general intelligence: Verbal Comprehension (VCI), Perceptual Reasoning (PRI), Working Memory (WMI), Processing Speed (PSI) and Full-Scale IQ (FSIQ) (Wechsler, WISC-IV Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV. Technical Manual, 2007). The current Weschler Scales are based on the following hypotheses (Wechsler, 2007):

1. Using the tests, it is possible to quantify a complex phenomenon such as intelligence, considering its various component factors.

2. Intelligence must be defined as the potential that allows the individual to confront and resolve particular situations.

3. Intelligence is necessarily related to the biological compounds of the organism.

The Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) expresses abilities in the formation of verbal concepts, relationships between concepts, richness, and precision in word definitions, social understanding, practical judgment, acquired knowledge, agility, and verbal intuition. The Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) expresses constructive praxis abilities, formation and classification of nonverbal concepts, visual analysis, and simultaneous processing.

The Working Memory Index (WMI) analyzes the capacity to retain and store information, mentally operate with it, transform it, and generate new information.

The Processing Speed Index (PSI) measures the ability to focus attention and explore, order, and/or discriminate visual information quickly and efficiently.

Finally, the Total Intelligence Quotient (TIQ) includes the scores for the four indices and provides a relative measure of the cognitive functioning or general ability of the person being evaluated with respect to the subjects in the normative group (that is, a group of children of the same age).

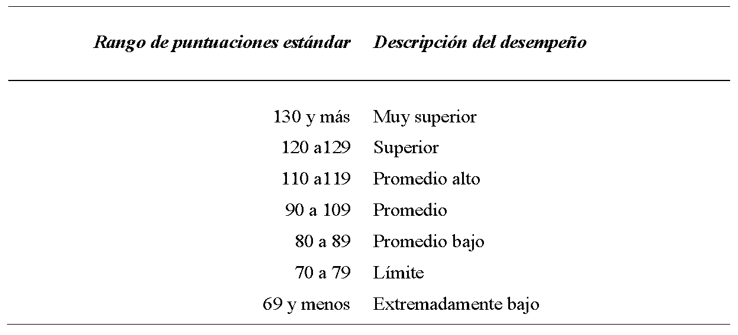

The examiner only has to report the percentile rank associated with the scalar scores obtained from the child. Quick reference 4-1 presents a practical guide to locating the tables in the WISC-IV Administration Manual (Wechsler, 2007) and the WISC-IV Technical Manual (Wechsler, 2007), which the examiner will need in order to convert raw scores to scaled scores and standard scores, to convert the sums of the scaled scores to the CIT and the Indices, and to obtain the confidence intervals and percentile ranks. Examiners should always report standard scores with their associated confidence intervals. The WISC-IV system, found in figure 1, is the most traditional of the three and recommended by the test's editor (Flanagan & Kaufman, 2012).

Figure 1. Traditional descriptive system for the WISC-IV (Taken from Wechsler, WISC-IV Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV. Technical manual, 2007)

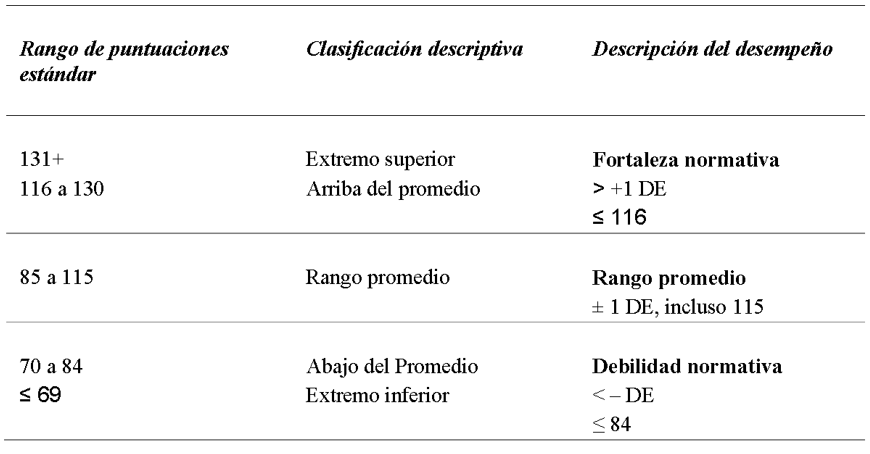

The normative, descriptive system, which appears in figure 2, is the one most used by neuropsychologists and will become the most used by clinical and educational psychologists (Flanagan, Ortiz & Alfonso, 2007; Flanagan et al., 2002, 2006; Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004 cited in Flanagan & Kaufman, 2012).

Finally, it should be noted that the WISC-IV was standardized in the United States with a sample of 2200 subjects and in Spain with a sample of 1485 subjects, in all cases aged between 6 and 16 years. Both the original American version and the Spanish adaptation offer results with special groups.

Figure 2. Normative descriptive system for the WISC-IV (Taken from Flanagan & Kaufman, 2012 p. 118)

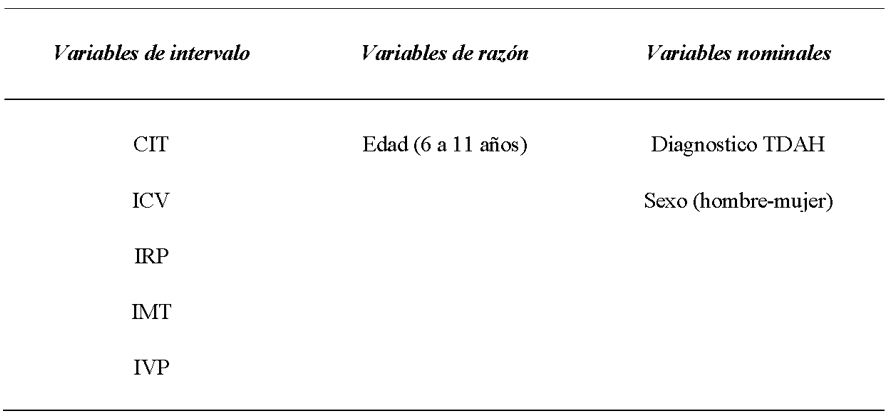

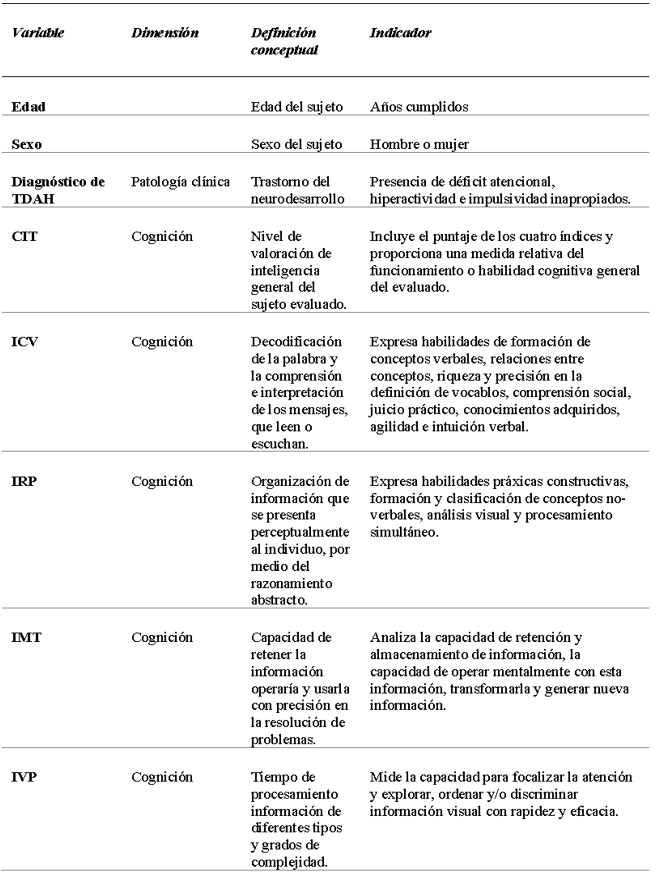

Categorization and Operationalization of Variables

The evaluation obtained on the WISC-IV Scale: Intelligence Quotient (IQ), indices of Verbal Comprehension (VCI), Perceptual Reasoning (PRI), Working Memory (WMI), and Processing Speed (PSI) are all numerical and interval variables, due to their properties, since their values allow comparisons to be made.

The variable sex (male-female) corresponds to the nominal dichotomous level of measurement, as it corresponds to the quality of the subjects. The variable Age (6 to 11 years) is a ratio variable due to its numerical quality. Finally, the variable Group with ADHD diagnosis, Group without ADHD, is a nominal variable.

Figure 3. Categorization of study variables

Figure 4. Operationalization of the study variables

RESULTS

For the analysis of results, IBM SPSS Statistics Standard, version 24.0.0.0, was used, based on the hypothetical construct of cognitive evaluation, that is, to obtain the differences in the results of each cognitive index and total intellectual coefficient (from WISC-IV) of each subject. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated.

The parametric Student's T-test for the PVI obtained significant differences (T=0,036 two-tailed sig.), so the equality and means hypothesis is rejected. Therefore, it is concluded that the exposed index (PVI) for the group diagnosed with ADHD and the group diagnosed without ADHD is not the same (PVI ADHD > PVI without ADHD).

Contrary to previous results, in Pearson's correlation coefficient, the group with ADHD presented in the same IVP a delay, demonstrated with a moderate and negative significance, in correlation with the increase of the age of the subject with 0,006 (p < 0,01 bilateral).

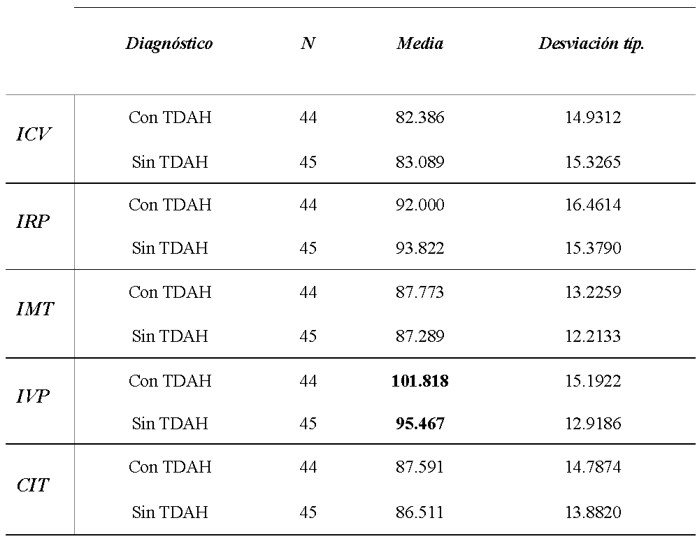

Statistics by Diagnostic Group

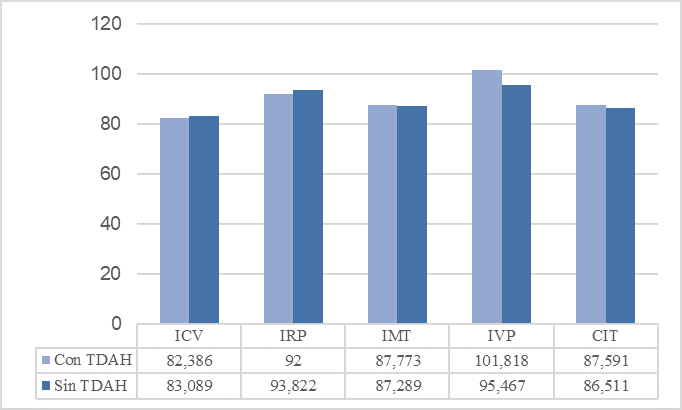

As shown below, the overall averages obtained from the different indexes indicate, in the group with ADHD (N- 44 subjects), an average obtained corresponding to TCI of 87,591 and for the group without ADHD (N- 45 subjects) of 86,511; both corresponding to a total intellectual coefficient in the Average Range according to the normative, descriptive system, with an IQ score between 85 and 115, it is noted that the group diagnosed with ADHD scores 1,08 points above the average of the group without ADHD, which does not represent a significant disparity in the Intelligence Quotient (figure 5).

Figure 5. Overall averages obtained by both groups, in the different indexes and total IQ (Author's own creation)

The index with the most significant average disparity between the diagnostic groups is the PVI (Illustration 4), with an average of 101,818 for the ADHD group and 95,467 for the group without ADHD (6351 ADHD>no ADHD).

Figure 6. Of the general averages obtained by both diagnostic groups in cognitive indexes and total IQ (Author's own creation)

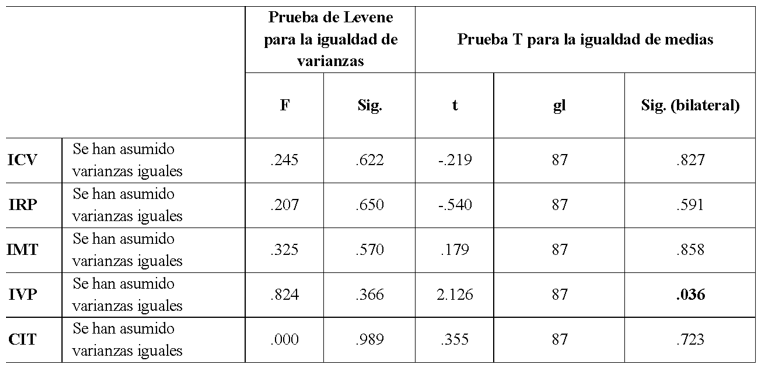

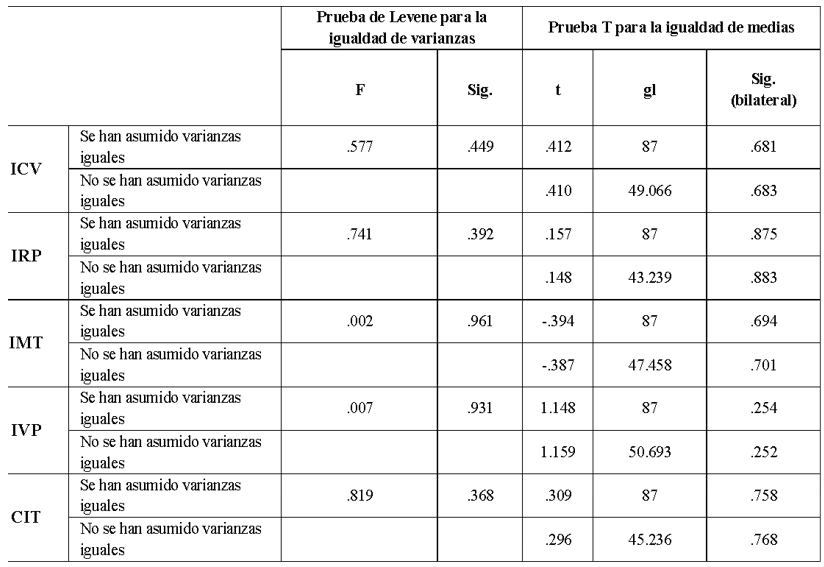

Subsequently, in Levene's contrast (F) on homogeneity or equality of variance. The result of this contrast in the first four indices, according to the established confidence level (95 %) and considering that the F value is more significant than 0,05, is assumed to be equal to the population variances.

Taking the t-values from the columns that assume equal variances, the significant result is as follows: in the case of the IVP, the obtained Student's t-value (two-tailed sig.) is 0,036, thus rejecting the hypothesis of equality, there are significant differences since it is less than 0,05. 05, the equality of means is rejected, and it is concluded that the index exposed (IVP) for the group diagnosed with ADHD and the group diagnosed without ADHD is not the same (ADHD>no ADHD) according to the parametric analysis of the T-test for equality of means (figura 7).

Figure 7. Results obtained in the T-Test for equality of means by diagnostic group (Author's own creation)

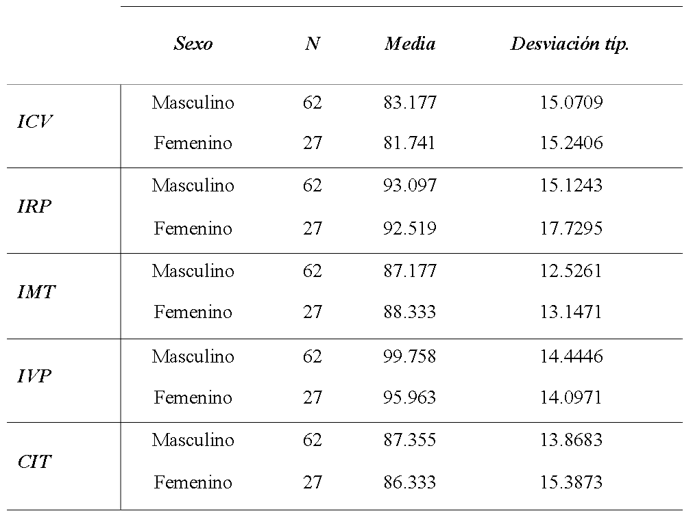

Statistics by Gender

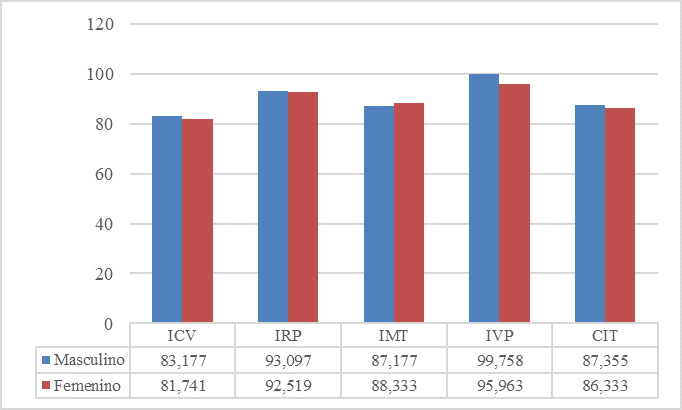

Although the present study intends to describe differences according to the diagnostic group, it was decided to carry out the same parametric test for the nominal dichotomous variable of the subject's gender. This clarifies possible differences that are not expected in the results. The following figure 8 shows that of the total number of participants (N- 89), 62 evaluations (69,66 %) correspond to males and 27 evaluations (30,33 %) to females. The average scores obtained in the different indexes and the CIT are shown.

Figure 8. Overall averages obtained by sex, in the different indexes and total IQ (Author's own creation)

In the same way as in the previous contrast, shown below (figure 10), the first is Levene's test (F) for homogeneity or equality of variance. The result of this contrast in the first four indexes, according to the established level of significance (95 %) and considering that the F value is more significant than 0,05, is assumed to be equal to the population variances. Taking the t-values from the columns that assume equal variances, the significant result is as follows: there are no significant differences, and the inequality of significant differences by sex is rejected.

Figure 9. Graph of the general averages obtained by sex in cognitive indexes and total IQ (Author's own creation)

Figure 10. Results obtained in the T-Test for equality of means by sex (Author's own creation)

Correlations

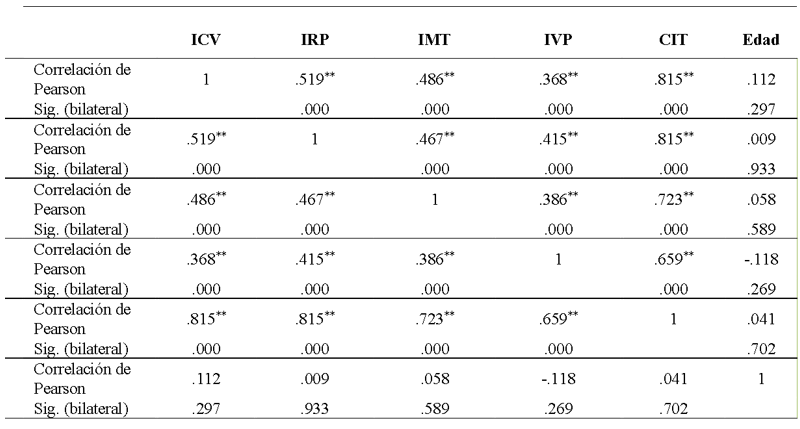

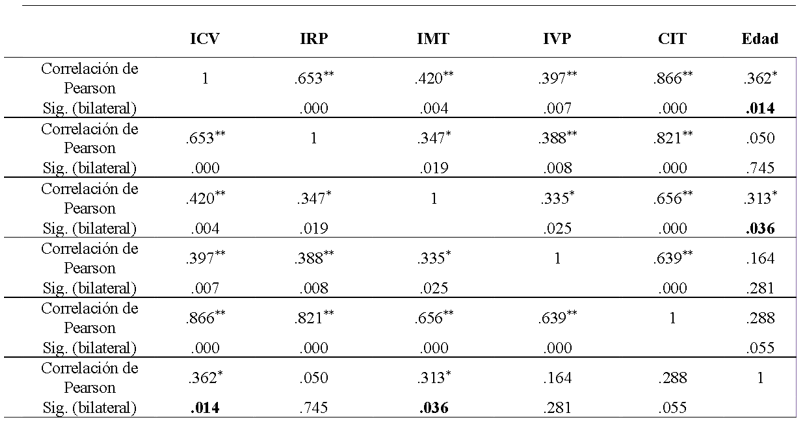

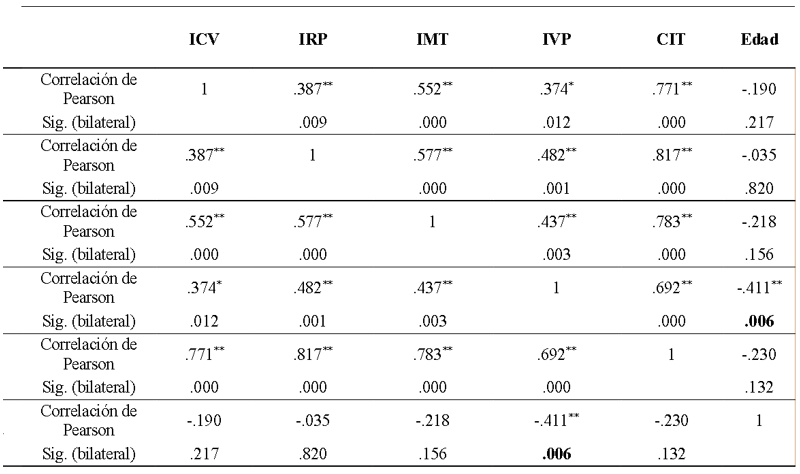

Because the variables of the cognitive indexes, the total IQ, and the age of the subjects correspond to an interval-ratio type of measurement, Pearson's correlation coefficient (p) analysis was carried out as a statistical test. For the reader's correct interpretation, Pearson's values are presented with **: the correlation is significant at the 0,01 level (bilateral), and *: the correlation is significant at the 0,05 level (bilateral).

Low, positive, significant correlations were obtained in the analysis of subjects without ADHD (figure 12) of the VCI with 0,014 (bilateral sig.) and of the TMI with 0,036 (bilateral sig.) in correlation to the increase in the age of the subject, which does not represent an unexpected finding (p < 0,05 bilateral).

In contrast to the previous group, in the results obtained in the group with ADHD (figure 13), the PVI had a moderate and negative significance in correlation with the increase in the age of the subject with 0,006 (P < 0,01 two-tailed).

Figure 11. Pearson's Correlation Coefficient Results for the total study population (Author's own creation)

Figure 12. Pearson's Correlation Coefficient results for the group without ADHD (Author's own creation)

Figure 13. Pearson's Correlation Coefficient Results for the group with ADHD (Author's own creation)

Hypothesis Test

The results presented above provide empirical evidence for the hypothesis that significant differences exist in the Cognitive Indices of each clinical group.

The difference is significant and characterizes the ADHD group with a cognitive profile where the Processing Speed Index (PSI) is higher than in the group without ADHD; the latter acquired lower scores in processing speed. However, a higher score in TMT and VCT was obtained in correlation to the increase in age, which was not an unexpected result. However, contradicting the initial finding, the PVI of the group with ADHD showed a loss of score in correlation to the increase in age of the subjects. However, in the results of the PRI and TCI, no significant disparities exist in any clinical group.

Statistical Testing Hypothesis

General Hypotheses

Hi is accepted: there are significant differences (with a level of 0,05) in the cognitive profile obtained from the WISC-IV test of two groups, one of children diagnosed with ADHD and the other of children without the disorder.

Ho is rejected: no significant differences (at the 0,05 level) in the cognitive profile obtained from the WISC-IV test of two groups, one of children diagnosed with ADHD and the other of children without the disorder.

Specific hypotheses

Hi1 is rejected: there are significant differences between the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) scores obtained in children diagnosed with ADHD and those without ADHD.

Ho1 is accepted: there is no significant difference between the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) scores obtained in children diagnosed with ADHD and those without ADHD.

Hi2 is rejected: there are significant differences between the scores obtained in the Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) in children diagnosed with ADHD and those without ADHD.

Ho2 is accepted: there is no significant difference between the scores obtained in the Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) in children diagnosed with ADHD and those without ADHD.

Hi3 is rejected: there are significant differences between the scores obtained in the Working Memory Index (WMI) in children diagnosed with ADHD and those without ADHD.

Ho3 is accepted: there is no significant difference between the scores obtained in the Working Memory Index (WMI) in children diagnosed with ADHD and those without ADHD.

Hi4 is accepted: there are significant differences between the scores obtained in the Processing Speed Index (PSI) in children diagnosed with ADHD and those who do not have ADHD.

Ho4 is rejected: there is no significant difference between the scores obtained in the Processing Speed Index (PSI) in children diagnosed with ADHD and those who do not have ADHD.

Hi5 is rejected: significant differences exist between the total IQ score obtained in children diagnosed with ADHD and those without ADHD.

Ho5 is accepted: no significant difference exists between the total IQ score obtained in children diagnosed with ADHD and those without ADHD.

DISCUSSION

The present investigation aims to describe and compare the cognitive processes that present differences in subjects with ADHD in the Altos region to promote research and understanding of this disorder. It is pointed out that the viability and structural validity of the use of the Wechsler Scale is found by Gómez, Vance, & Watson (2016), who, through the use of the WISC-IV intelligence scale, set themselves the objective of studying the application of WISC-IV in children with ADHD. The results obtained indicate the guidelines for its reproduction.

Using the complete application of WISC-IV to obtain the IQ as a tool for the analysis of the cognitive processes that present deficiencies in ADHD, the processes that are most relevant in this research are working memory, processing speed, attention, verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning, and processing speed. Styck and Watkins (2017) observed that the application of WISC-IV provided more reliable information and, therefore, recommended its use to obtain the interpretation of the full-scale IQ used for this study. Although this is not the case, we will have to take into consideration the study carried out by Antshel et al. (2007), which concluded that children with a high IQ and ADHD showed a pattern of familiarity, as well as cognitive, psychiatric, and behavioral characteristics consistent with the diagnosis of ADHD in children with average IQ. These data suggest that the diagnosis of ADHD is valid in children with high IQs, so it should be considered that the CIT may or may not present variances in its score, and it will be necessary to precisely delimit the cognitive profile with the indices in contrast to the specific executive functions.

Focusing the discussion on the most relevant aspects extracted from the results, we can agree that there is a minimal difference between subjects with ADHD and subjects without ADHD. The most relevant finding in the CIT is that the group with ADHD scores 1. 08 points above the group without ADHD, but despite the difference, both are within the average range according to the normative, descriptive system, with an IQ between 85 and 115 points. This infers that the intellectual capacity of both groups is preserved and is within the normal range (Jepsen, Fagerlund, & Mortensen, 2009). The same authors point out that the associations between IQ and attention deficits in ADHD are generally modest, with a medium influence on the IQ that probably amounts to 2 or 5 IQ points. (Jepsen, Fagerlund, & Mortensen, 2009). Therefore, it is in line with our result, where the variance in the processing speed in our subjects does not influence the total IQ.

The analysis of the results shows that the index with the most significant disparity is the PVI since the group with ADHD obtained a score of 101,818 and the group without ADHD only 95,467, which represents a difference of 6,351, which highlights the ability of the subjects to respond quickly to the solution. 818, and the group without ADHD only 95,467, which represents a difference of 6,351, which highlights that the ability of the subjects to respond promptly to conflict resolution is not affected in both groups, therefore contrasting with the above (Fenollar, Navarro, González, & García, 2015) where they pointed out similar findings in children with ADHD, specifically the ADHD-D (inattentive or distractible) and ADHD-C (combined) subgroups with an apparent deficit in the processing speed index.

The results obtained provide us with an important finding: the group with ADHD presents a higher speed index than the group without ADHD. However, the latter compensates for this lower score by presenting a higher verbal comprehension, comparing the results obtained by (Fenollar, Navarro, González, & García, 2015), in which processing speed presents deficiencies in the groups that present ADHD.

The hypothesis proposed by us is that there is inequality between the two groups in the processing speed index, which, through data analysis, clearly denotes the difference between the two groups, highlighting the superiority of the group with ADHD, a characteristic of the non-representative sample of the population of Tepatitlán, supporting the findings of Thaler, Bello and Etcoff (2013), where they demonstrated that children with inattentive subtype ADHD had deficient scores on the Processing Speed index.

According to Thorsen et al. (2018), processing speed is one of the main tools available to school-age children, making it difficult to socialize with their peers.

Contrary to Thorsen (2018), the results obtained in our research show a high processing speed index in subjects with ADHD, but this does not show development, causing a lower level of this function at higher ages, which represents an unexpected finding in the research, which, in turn, agrees with the results of Thorsen (2018)

According to other authors (Walg, Hapfelmeier, El-Wahsch, & Prior, 2017) (Caspersen, Petersen, Vangkilde, Plessen, & Habekost, 2017) (Cook, Braaten, & Surman, 2018) (Adalio, Owens, McBurnett, Hinshaw, & Pfiffne, 2017), the PVI is one of the cognitive processes that is most closely related to the behavioral deficiencies presented by subjects with ADHD. In our results, this index is favored at early ages, but it deteriorates as the subject's age increases, causing very significant deficiency at an age closer to adolescence.

Contrary to what Thaler, Bello, and Etcoff (2013), children with inattentive subtype ADHD had deficient scores on the PVI and, similarly, this index, together with the TMI, was associated with impaired behavioral functioning in children with ADHD, it could not be considered as a reference for this study because the categorization of ADHD subtypes was not performed. However, it is also accepted that significant differences exist between the scores obtained in the Processing Speed Index (PSI), which measures the ability to focus attention and explore, order, and/or discriminate visual information quickly and efficiently. Nevertheless, it was demonstrated here that children diagnosed with ADHD have a higher evaluation than those not diagnosed with ADHD, and this result was not expected.

The latter generates the most relevant finding of the study: generating a cognitive profile of the subject with ADHD in the range of 6 to 11 years of age.

Based on the results obtained, it can be affirmed that, as expected, significant differences have been found, with the group with ADHD presenting the most significant variation in the expected results. Furthermore, the fact that there are no significant differences in IQ is consistent with the results previously described by Carlson (2000, cited in Carlson & Mann, 2000) and which are contrary to what is mentioned by Bridgett (2006) and The American Psychiatric Association (2013), which state that subjects with Attention Deficit Disorder have a lower intellectual level compared to the general population, or that they may achieve lower academic and intellectual development levels in contrast to those obtained by their peers, verified by individual tests, which seems to be somewhat lower than that of other children, because the IQ did not show significant differences.

It is accepted that there are significant differences between the scores obtained in the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI), where children diagnosed with ADHD score lower than those diagnosed without ADHD, which expresses abilities in the formation of verbal concepts, relationships between concepts, richness, and precision in the definition of words, social understanding, practical judgment, acquired knowledge, agility, and verbal intuition. Finally, we are dealing with a condition of attention deficit, which was to be expected.

Finally, as a third specific objective, the aim was to generate a theoretical contribution to help understand ADHD and the application of intelligence scales for subjects who present it. It should be noted that the theoretical and methodological contrasts, rather than being opposed, showed an evolutionary process of adaptation of praxis to the problem. Hence, the only intention was to make a historical reference to both processes, which is considered complete for the stated objective.

CONCLUSIONS

Firstly, and of great importance, it should be mentioned that in both groups, there are no significant differences in IQ. Therefore, there is no inequality in the level of assessment of general intelligence. Therefore, a relative general cognitive functioning or ability difference should not be assumed.

Finally, the ADHD diagnostic group demonstrated a significantly higher PVI score compared to the group without ADHD. This indicates a superior characteristic in the processing time of information of different types and degrees of complexity, which translates into a greater capacity to focus attention and explore, organize, and/or discriminate visual information quickly and efficiently.

However, this same index (IVP) showed a loss of score with increasing age in subjects with the disorder, denoting a moderate and negative significance in correlation with age because the children in the clinical group with ADHD aged 6 years presented the maximum score and the children aged 11 years the lowest. This describes the existence of a reduction in the development of processing speed according to the age range in their growth. A delay in the ability to focus and discriminate visual information, which progressively deteriorates. This refers to diagnostic criteria of the disorder, such as being easily distracted by irrelevant stimuli. However, this was not initially the case.

Low and positive significant correlations were also obtained in the analysis of subjects without ADHD in the VCI: a slight improvement in the decoding of words and the comprehension and interpretation of messages that they read or listen to, and in the MTI, a significant but low improvement in the ability to retain operational information and use it with precision in problem-solving, which is not an unexpected finding.

From the above, it can be concluded that the study provides important findings for identifying the cognitive profile, which encourages a more fantastic approach to the study, treatment, and/or psychological or pedagogical intervention of children with ADHD in the region.

1. Adalio CJ, Owens EB, McBurnett K, Hinshaw SP, Pfiffne LJ. Processing Speed Predicts Behavioral Treatment Outcomes in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Predominantly Inattentive Type. J Abnorm Child Psychol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Mar 7];46(4):701–11. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10802-017-0336-z

2. Aguilar Cárceles MM, Morillas Cueva L. El trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH): aspectos jurídico-penales, psicológicos y criminológicos. Madrid: Dykinson; 2014.

3. Ajuriaguerra J. Manual de psiquiatría infantil. 4th ed. Barcelona: Masson; 2002.

4. Álvarez-Arboleda LM, Rodríguez-Arocho WC, Moreno-Torres MA. Evaluación neurocognoscitiva de Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad. Perspect Psicol. 2003;85–92.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales. Barcelona: Masson; 2002.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. American Psychological Association. APA Diccionario Conciso de Psicología. México: Manual Moderno; 2010.

8. American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of Psychologists and Code of conduct [Internet]. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/principles.pdf

9. Anastasi A, Urbina S. Tests psicológicos. 7th ed. Ortíz Salinas ME, translator. México: Prentice Hall; 1998.

10. Anderson JR. Aprendizaje y memoria. Un enfoque integral. 2nd ed. México D.F.: McGraw-Hill/Interamericana; 2001.

11. Andrés-Pueyo A, Colom R. El estudio de la inteligencia humana: recapitulación ante el cambio de milenio. Psicothema. 1999;11(3):453–76.

12. Antshel KM, Faraone SV, Stallone K, Nave A, Kaufmann FA, Doyle A, et al. Is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder a valid diagnosis in the presence of high IQ? Results from the MGH Longitudinal Family Studies of ADHD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;687–94. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01735.x

13. Aragón EL. Evaluación Psicológica: Historia, fundamentos teórico-conceptuales y psicometría. Tovar Sosa MA, editor. México: El Manual Moderno; 2011.

14. Aragón LE, Silva A. Evaluación psicológica en el área educativa. 1st ed. México: Pax México; 2002.

15. Aragonés Benaiges E, Piñol JL, Cañisá A, Caballero A. Cribado para el trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad en pacientes adultos de atención primaria. Rev Neurol. 2013;56(9):449–55.

16. Ardila A, Rosselli M, Villaseñor EM. Neuropsicología de los trastornos del aprendizaje. 1st ed. México D.F.: Manual Moderno; 2005.

17. Baddeley A. Working memory. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci [Internet]. 1983 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Mar 7];302(1110):311–24. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2395996

18. Barkley RA. Distinguishing Sluggish Cognitive Tempo From ADHD in Children and Adolescents: Executive Functioning, Impairment, and Comorbidity. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2025 Mar 7];161–73. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.734259

19. Barkley RA. La importancia de las emociones. XI Jornada sobre Déficit de Atención e Hiperactividad. TDAH: UNA EVIDENCIA CIENTÍFICA [Internet]. Madrid, España; 2013 Dic 11 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.educacionactiva.com/

20. Barkley RA. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. 4th ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015.

21. Barkley RA, Peters H. The earliest reference to ADHD in the medical literature? Melchior Adam Weikard's description in 1775 of "attention deficit" (Mangel der Aufmerksamkeit, Attentio Volubilis). J Atten Disord. 2012;16(8):623–30. doi:10.1177/1087054711432309

22. Barkley RA, DuPaul GJ, McMurray MB. Comprehensive evaluation of attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity as defined by research criteria. J Consult Clin Psychol [Internet]. 1990 [cited 2025 Mar 7];58(6):775–89. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.775

23. Barragán Pérez E, De la Peña F. Primer Consenso Latinoamericano y declaración de México para el trastorno de déficit de atención e hiperactividad en Latinoamérica. Rev Med Hondur. 2008;76(1):33–8.

24. Barrios O, Matute E, Ramírez-Dueñas M, Chamorro Y, Trejo S, Bolaños L. Características del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad en escolares mexicanos de acuerdo con la percepción de los padres. Suma Psicol [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 Mar 7];23(2):101–8. doi:10.1016/j.sumpsi.2016.05.001

25. Bergwerff CE, Luman M, Weeda WD, Oosterlaan J. Neurocognitive profiles in children with ADHD and their predictive value for functional outcomes. J Atten Disord. 2017;1–11. doi:10.1177/1087054716688533

26. Bohórquez Montoya LF, Cabal Álvarez MA, Quijano Martínez MC. La comprensión verbal y la lectura en niños con y sin retraso lector. Pensam Psicol. 2014;12(1):169–82. doi:10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI12-1.cvln

27. Brennan JF. Historia y sistemas de la psicología. 5th ed. Dávila Martínez JF, translator. México: Prentice Hall; 1999.

28. Bridgett DJ, Walker ME. Intellectual functioning in adults with ADHD: A meta-analytic examination of full scale IQ differences between adults with and without ADHD. Psychol Assess [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2025 Mar 7];18(1):1–14. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.1

29. Brown TE. Comorbilidad del TDAH. Manual de las complicaciones del trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad en niños y adultos. 2nd ed. Barcelona, España: Masson; 2010.

30. Bruning R, Schraw G, Norby M. Psicología cognitiva y de la instrucción. 5th ed. Martín Cordero JI, Luzón Encabo JM, Martín Blecua E, translators. Madrid, España: Pearson Educación; 2012.

31. Burgaleta Díaz DM. Velocidad de procesamiento, eficiencia cognitiva e integridad de la materia blanca: Un análisis de imagen por tensor de difusión [doctoral thesis]. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Facultad de Psicología; 2011.

32. Bustillo M, Servera M. Análisis del patrón de rendimiento de una muestra de niños con TDAH en el WISC-IV. Rev Psicol Clín Niños Adolesc. 2015 Jul;2(2):121–8.

33. Cantero Caja A. Nueva Comercialización del WISC-IV [Internet]. 2011 Dec [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: Dialnet-NuevaComercializacionDelWISCIV-3800737.pdf

34. Cardo E, Servera M. Trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad: estado de la cuestión y futuras líneas de investigación. Rev Neurol. 2008;46:365–72.

35. Carlson C, Mann M. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, predominantly inattentive subtype. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2000 Jul;9(3):499–510.

36. Carroll JB. Psychometrics, intelligence, and public perception. Intelligence. 1997;24(1):25–52.

37. Caspersen ID, Petersen A, Vangkilde S, Plessen KJ, Habekost T. Perceptual and response-dependent profiles of attention in children with ADHD. Neuropsychology. 2017;31(4):349–60.

38. Castellanos FX, Tannock R. Neuroscience of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the search for endophenotypes. Nat Rev Neurosci [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2025 Mar 7];3:617–28. doi:10.1038/nrn896

39. Castroviejo IP. Síndrome de déficit de atención-hiperactividad. 4th ed. Madrid, España: Díaz de Santos; 2009.

40. Chang Z, D’Onofrio B, Quinn P, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H. Medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk for depression: A Nationwide Longitudinal Cohort Study. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:916–22.

41. Cidoncha Delgado AI. Niños con Déficit de Atención por Hiperactividad TDAH: Una realidad social en el aula. Autodidacta. 2010;31–6.

42. Clemow DB, Bushe C, Mancini M, Ossipov MH, Upadhyaya H. A review of the efficacy of atomoxetine in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adult patients with common comorbidities. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:357–71. doi:10.2147/NDT.S115707.

43. Cochran SD, Drescher J, Kismödi E, Giami A, García-Moreno C, Atalla E, et al. Proposed declassification of disease categories related to sexual orientation in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11). Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(9):672–9. doi:10.2471/BLT.14.135541

44. Cohen RJ, Swerdlik ME. Pruebas y evaluación psicológicas: introducción a las pruebas y a la medición. 6th ed. Izquierdo M, translator. México: Pearson Educación; 2006.

45. Castañeda S, Pontón Becerril GE, Padilla Sierra S, Olivares Bari M, Pérez de Lara Choy MI, translators. México D.F.: McGraw-Hill/Interamericana.

46. Colom R, Flores-Mendoza C. Inteligencia y Memoria de Trabajo: La Relación Entre Factor G, Complejidad Cognitiva y Capacidad de Procesamiento. Psicol Teor Pesq. 2001;17(1):37–47.

47. Condemarín M, Gorostegui ME, Milicic N. Déficit atencional, estrategias para el diagnóstico y la intervención psicoeducativa. 4th ed. Santiago, Chile: Ariel, Planeta Chilena; 2005.

48. Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Psicólogos de España. Evaluación de Test WISC-IV [Internet]. Madrid; 2005 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.cop.es/uploads/PDF/WISC-IV.pdf

49. Cook NE, Braaten EB, Surman CB. Clinical and functional correlates of processing speed in pediatric Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Neuropsychol. 2018;24(5):598–616. doi:10.1080/09297049.2017.1307952

50. Coolican H. Métodos de investigación y estadística en psicología. 2nd ed. García Mulusa M, translator. México: El Manual Moderno; 1997.

51. Cornejo E, Fajardo B, López V, Soto J, Ceja H. Prevalencia de déficit de atención e hiperactividad en escolares de la zona noreste de Jalisco, México. Rev Méd MD. 2015;6(3):190–5.

52. Cosculluela A, Andrés A, Tous JM. Inteligencia y velocidad o eficiencia del proceso de información. Anu Psicol. 1992;52:67–77.

53. Crichton A. An Inquiry Into the Nature and Origin of Mental Derangement: Comprehending a Concise System of the Physiology and Pathology of the Human Mind. Vol. I. Cadell Jr, Davies W, editors. London; 1798.

54. Crowe SF. Does the Letter Number Sequencing Task Measure Anything More Than Digit Span? Assess. 2000;7(2):113–7.

55. Cruz L, Ramos A, Gutiérrez M, Gutiérrez D, Márquez A, Ramírez D, et al. Prevalencia del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad en escolares de tres poblaciones del estado de Jalisco. Rev Mex Neurocienc. 2010;11(1):15–9.

56. Daley D, Birchwood J. ADHD and academic performance: why does ADHD impact on academic performance and what can be done to support ADHD children in the classroom? Child Care Health Dev. 2009;36(4):455–64.

57. Darwin C. El Origen de las especies por medio de la selección natural. Madrid; 1921.

58. De la Osa Langreo A, Mulas F, Mattos L, Gandía Benetó R. Trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad: a favor del origen orgánico. Rev Neurol. 2007;44(3):47–9.

59. De la Peña F, Palacio J, Barragán E. Declaración de Cartagena para el Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad (TDAH): rompiendo el estigma. Rev Cienc Salud. 2010;8(1):93–8.

60. Duñó Ambrós L. TDAH infantil y metilfenidato: predictores clínicos de respuesta al tratamiento [doctoral thesis]. Barcelona, España: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Psiquiatría y Medicina Legal; 2015 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/142657

61. Etchepareborda M, Abad-Mas L. Memoria de trabajo en los procesos básicos del aprendizaje. Rev Neurol. 2005;40(Suppl 1):S79–83.

62. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Consensus Statement on ADHD. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2002;5(2):96–8. doi:10.1007/s007870200

63. Eysenck HJ, Arnold W, Meili R. Encyclopedia of psychology. Unabridged ed. New York: Continuum; 1982.

64. Fass PS. The IQ: A Cultural and Historical Framework. Am J Educ. 1980;88(4):431–58.

65. Fenollar J, Navarro I, González C, García J. Detección de perfiles cognitivos mediante WISC-IV en niños diagnosticados de TDAH: ¿Existen diferencias entre subtipos? Rev Psicodidáct. 2015;20(1):157–76.

66. Fernández L. La perversión de la psicología de la inteligencia: respuesta a Colom. Rev Galego-Port Psicol Educ. 2007;14(1):21–36.

67. Fernández-Jaén A, Fernández-Mayoralas D, Calleja-Pérez B, Muñoz-Jareño N, López-Arribas S. Endofenotipos genómicos del trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad. Rev Neurol. 2012;54(1):81–7.

68. Fernández-Mayoralas DM, Fernández-Perrone A, Fernández-Jaén A. Trastornos específicos del aprendizaje y trastorno hiperactividad. Adolescere. 2013;69–75.

69. Flanagan DP, Kaufman AS. Claves para la evaluación con WISC-IV. México D.F.: Manual Moderno; 2012.

70. Flavell JH. Cognitive development. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1985.

71. Franke B, Faraone SV, Asherson P, Buitelaar J, Bau CH, Ramos-Quiroga JA. The genetics of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, a review. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;10:960–87.

72. Fuenmayor G, Villasmil Y. La percepción, la atención y la memoria como procesos cognitivos utilizados para la comprensión textual. Rev Artes Humanid UNICA. 2008;9(22):187–202.

73. García González E. Piaget: la formación de la inteligencia. 2nd ed. México: Trillas; 1991.

74. García Sevilla J. Psicología de la atención. Madrid, España: Síntesis; 1997.

75. García-Losa E. Retrospectiva y reflexiones sobre el Síndrome de Disfunción Cerebral Mínima. Psiquis Rev Psiquiatr Psicol Méd Psicosom. 1997;53–8.

76. Gardner H. Estructuras de la mente. La teoría de las inteligencias múltiples. México: FCE; 2001.

77. Gaxiola Gaxiola KG. Disturbance of the emotion and motivation in ADHD: a dopaminergic dysfunction. Graf Discipl UCPR. 2015;(28):39–50.

78. Gerlach M, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Rohde LA, Romanos M. What are the benefits of methylphenidate as a treatment for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? ADHD Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017;1–3. doi:10.1007/s12402-017-0220-2

79. Gómez AI. Procesos psicológicos básicos. Tlalnepantla, Estado de México: RED Tercer Milenio; 2012.

80. Gómez R, Vance A, Watson SD. Structure of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fourth Edition in a group of children with ADHD. Front Psychol. 2016 May 30;7(737):1–11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00737

81. Gómez-Pezuela Gamboa G. Desarrollo psicológico y aprendizaje. 1st ed. México: Trillas; 2007.

82. González Garrido AA, Ramos Loyo J. La atención y sus alteraciones: del cerebro a la conducta. Orta EM, editor. Distrito Federal, México: El Manual Moderno; 2006.

83. Gorga M. Trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad y el mejoramiento cognitivo: ¿Cuál es la responsabilidad del médico? Rev Bioética. 2013;21(2):241–50.

84. Gregory RJ. Pruebas psicológicas: historia, principios y aplicaciones. 6th ed. Vega Pérez M, editor. Ortíz Salinas ME, Pineda Ayala LE, translators. México: Pearson Educación; 2012.

85. Hancock MD. The Misdiagnosing of Children of ADHD. Integr Stud. 2017;112.

86. Herrera-Narváez G. Reflexiones sobre el Déficit Atencional con Hiperactividad (TDAH) y sus implicancias educativas. Horiz Educ. 2005;10(1):51–6.

87. Howell R, Hewards W, Swassing H. Los alumnos superdotados. In: Herward WL, editor. Niños Excepcionales una introducción a la educación especial. 5th ed. Madrid: Prentice Hall; 1998. p. 433–81.

88. Jara Segura AB. El TDAH, Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad, en las clasificaciones diagnósticas actuales (CIE-10, DSM-IV–R y CFTMEA–R 2000). Norte Salud Ment. 2009;(35):30–40.

89. Jensen AR. Clocking the mind. New York: Elsevier; 2006.

90. Jepsen JR, Fagerlund B, Mortensen EL. Do attention deficits influence IQ assessment in children and adolescents with ADHD? J Atten Disord [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2025 Mar 7];12(6):551–62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054708322996

91. Jiménez G. Prueba: Escala Wechsler de inteligencia para el nivel escolar (WISC-IV). Av Med. 2007;5:169–71.

92. Joffre-Velázquez V, García-Maldonado G, Joffre-Mora L. Trastorno por déficit de la atención e hiperactividad de la infancia a la vida adulta. Med Fam. 2007;9(4):176–81.

93. Juan-Espinosa M. La geografía de la inteligencia humana. Madrid: Pirámide; 1997.

94. Junqué C, Jódar M. Velocidad de procesamiento cognitivo en el envejecimiento. An Psicol. 1990;6(2):199–207.

95. Kail R. Speed of information processing: developmental change and links to intelligence. J Sch Psychol. 2000;38(1):51–61.

96. Ohlmeier MD, Peters K, Wildt BT, Zedler M, Ziegenbein M, Wiese B, et al. Comorbilidad de la dependencia a alcohol y drogas y el trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH). RET Rev Toxicol. 2009;(58):12–8.

97. Oliveira D, Sousa P, Borges dos Reis C, Virtuoso S, Tonin F, Sanches A. PMH3 - Meta-análisis de eficacia de la atomoxetina en adultos con trastorno de déficit de atención con hiperactividad. Value Health. 2017;20(9):A884. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.2632

98. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Décima revisión de la Clasificación Internacional de los Trastornos Mentales y del Comportamiento CIE-10. Descripciones clínicas y pautas para el diagnóstico. Meditor; 1992.

99. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Guía de bolsillo de la Clasificación de los Trastornos Mentales y del Comportamiento CIE-10. CDI Criterios diagnósticos de investigación. Médica Panamericana; 2000.

100. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Clasificación estadística internacional de enfermedades y problemas relacionados con la salud—10a revisión (CIE-10). 2003 ed. Vol. 1. Washington: OPS; 1996.

101. Osuna Á. Evaluación neuropsicológica en educación. ReiDoCrea. 2017;6(2):24–30.

102. Otero MR. Psicología cognitiva, representaciones mentales e investigación en enseñanza de las ciencias. Investig Ensino Ciênc. 1999;4(2):93–119.

103. Pagano RR. Estadística para las ciencias del comportamiento. 9th ed. Baranda Torres M, translator. México D.F.: Cengage Learning; 2011.

104. Palacio JD, De la Peña F, Palacios-Cruz L, Ortiz-León S. Algoritmo latinoamericano de tratamiento multimodal del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH) a través de la vida. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2009;38(1):35S–65S.

105. Palacios–Cruz L, De la Peña F, Valderrama A, Patiño R, Calle Portugal SP, Ulloa RE. Conocimientos, creencias y actitudes en padres mexicanos acerca del trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad (TDAH). Salud Ment. 2011;34(2):149–55.

106. Palme ED, Finger S. An early description of ADHD (Inattentive Subtype): Dr Alexander Crichton and ‘Mental Restlessness’ (1798). Child Psychol Psychiatry Rev. 2001;6(2):66–73.

107. Pascual Lema S. The role of the clinical psychologist and the approach to ADHD. Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;37–53.

108. Pelayo-Terán JM, Trabajo-Vega P, Zapico-Merayo Y. Aspectos históricos y evolución del concepto de trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH): mitos y realidades. Cuad Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;11(1):7–35.

109. Peña del Agua AM. Las teorías de la inteligencia y la superdotación. Aula Abierta. 2004;84:23–38.

110. Pérez Hernández E, Corrochano Ovejero L. Aspectos neurobiológicos y etiopatogenia del TDAH y los trastornos relacionados. In: Ruiz Sánchez de León JM, Fournier del Castillo C, editors. Manual de neuropsicología pediátrica. Madrid, España: ISEP Madrid; 2016. p. 415–42. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3492.6968

111. Pérez Mariño N. Intervención sobre el funcionamiento ejecutivo en un caso de TDAH: implicaciones en conciencia fonológica y lectura. Rev Estud Investig Psicol Educ. 2015;(9):48–52.

112. Piaget J. El nacimiento de la inteligencia en el niño. Barcelona: Crítica; 2003.

113. Polanczyk G, Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8.

114. Presentación Herrero MJ, Siegenthaler Hierro R, Jara Jiménez P, Casas AM. Seguimiento de los efectos de una intervención psicosocial sobre la adaptación académica, emocional y social de niños con TDAH. Psicothema. 2010;22(4):778–83.

115. Pueyo AA. Manual de psicología diferencial. Madrid, España: McGraw-Hill; 1997.

116. Quintero Gutiérrez del Alamo FJ, Rodríguez-Quirós J, Correas J, Pérez-Templado J. Aspectos nutricionales en el trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad. Rev Neurol. 2009;49(6):307–12.

117. Rabito Alcón MF, Correas J. Guías para el tratamiento del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad: una revisión crítica. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2014;42(6):315–24.

118. Raven J, Raven JC, Court JH. Manual for Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. Oxford, England: Oxford Psychologists; 1998.

119. Rebollo M, Montiel S. Atención y funciones ejecutivas. Rev Neurol. 2006;46(Suppl 2):S3–7.

120. Ohlmeier MD, Peters K, Wildt BT, Zedler M, Ziegenbein M, Wiese B, et al. Comorbilidad de la dependencia a alcohol y drogas y el trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH). RET Rev Toxicol. 2009;(58):12–8.

121. Oliveira D, Sousa P, Borges dos Reis C, Virtuoso S, Tonin F, Sanches A. PMH3 - Meta-análisis de eficacia de la atomoxetina en adultos con trastorno de déficit de atención con hiperactividad. Value Health. 2017;20(9):A884. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.2632

122. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Décima revisión de la Clasificación Internacional de los Trastornos Mentales y del Comportamiento CIE-10. Descripciones clínicas y pautas para el diagnóstico. Meditor; 1992.

123. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Guía de bolsillo de la Clasificación de los Trastornos Mentales y del Comportamiento CIE-10. CDI Criterios diagnósticos de investigación. Médica Panamericana; 2000.

124. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Clasificación estadística internacional de enfermedades y problemas relacionados con la salud—10a revisión (CIE-10). 2003 ed. Vol. 1. Washington: OPS; 1996.

125. Osuna Á. Evaluación neuropsicológica en educación. ReiDoCrea. 2017;6(2):24–30.

126. Otero MR. Psicología cognitiva, representaciones mentales e investigación en enseñanza de las ciencias. Investig Ensino Ciênc. 1999;4(2):93–119.

127. Pagano RR. Estadística para las ciencias del comportamiento. 9th ed. Baranda Torres M, translator. México D.F.: Cengage Learning; 2011.

128. Palacio JD, De la Peña F, Palacios-Cruz L, Ortiz-León S. Algoritmo latinoamericano de tratamiento multimodal del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH) a través de la vida. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2009;38(1):35S–65S.

129. Palacios–Cruz L, De la Peña F, Valderrama A, Patiño R, Calle Portugal SP, Ulloa RE. Conocimientos, creencias y actitudes en padres mexicanos acerca del trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad (TDAH). Salud Ment. 2011;34(2):149–55.

130. Palme ED, Finger S. An early description of ADHD (Inattentive Subtype): Dr Alexander Crichton and ‘Mental Restlessness’ (1798). Child Psychol Psychiatry Rev. 2001;6(2):66–73.

131. Pascual Lema S. The role of the clinical psychologist and the approach to ADHD. Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;37–53.

132. Pelayo-Terán JM, Trabajo-Vega P, Zapico-Merayo Y. Aspectos históricos y evolución del concepto de trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH): mitos y realidades. Cuad Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;11(1):7–35.

133. Peña del Agua AM. Las teorías de la inteligencia y la superdotación. Aula Abierta. 2004;84:23–38.

134. Pérez Hernández E, Corrochano Ovejero L. Aspectos neurobiológicos y etiopatogenia del TDAH y los trastornos relacionados. In: Ruiz Sánchez de León JM, Fournier del Castillo C, editors. Manual de neuropsicología pediátrica. Madrid, España: ISEP Madrid; 2016. p. 415–42. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3492.6968

135. Pérez Mariño N. Intervención sobre el funcionamiento ejecutivo en un caso de TDAH: implicaciones en conciencia fonológica y lectura. Rev Estud Investig Psicol Educ. 2015;(9):48–52.

136. Piaget J. El nacimiento de la inteligencia en el niño. Barcelona: Crítica; 2003.

137. Polanczyk G, Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8.

138. Presentación Herrero MJ, Siegenthaler Hierro R, Jara Jiménez P, Casas AM. Seguimiento de los efectos de una intervención psicosocial sobre la adaptación académica, emocional y social de niños con TDAH. Psicothema. 2010;22(4):778–83.

139. Pueyo AA. Manual de psicología diferencial. Madrid, España: McGraw-Hill; 1997.

140. Quintero Gutiérrez del Alamo FJ, Rodríguez-Quirós J, Correas J, Pérez-Templado J. Aspectos nutricionales en el trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad. Rev Neurol. 2009;49(6):307–12.

141. Rabito Alcón MF, Correas J. Guías para el tratamiento del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad: una revisión crítica. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2014;42(6):315–24.

142. Raven J, Raven JC, Court JH. Manual for Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. Oxford, England: Oxford Psychologists; 1998.

143. Rebollo M, Montiel S. Atención y funciones ejecutivas. Rev Neurol. 2006;46(Suppl 2):S3–7.

144. Richardson J, Engle R, Hasher L, Logie R, Stoltzfus E, Zacks R. Working memory and human cognition. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996.

145. Rickel AU, Brown RT. Trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad. 1st ed. México D.F.: Manual Moderno; 2007.

146. Ríos Lago M, Lubrini G, Periáñez Morales JA, Viejo Sobera R, Tirapu Ustárroz J. Velocidad de procesamiento de la información. In: Tirapu Ustárroz J, editor. Neuropsicología de la corteza prefrontal y las funciones ejecutivas. Madrid: Viguera; 2012. p. 241–70.

147. Rodríguez-Salinas E, Navas M, González P, Fominaya S, Duelo M. La escuela y el trastorno por déficit de atención con/sin hiperactividad (TDAH). Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2006;75–98.

148. Ruiz JM, Guinea SF, González-Marqués J. Aspectos teóricos actuales de la memoria a largo plazo: de las dicotomías a los continuos. An Psicol. 2006 Dec;290–7.

149. Sanfeliu I. Disfunción cerebral mínima. Clín Anal Grup. 2010;104–5(32):279–83.

150. Santiago G, Tornay F, Gómez E, Elosúa M. Procesos psicológicos básicos. Madrid: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

151. Santrock J. Psicología de la educación. México: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

152. Santrock J. Psicología de la educación. México: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

153. Sastre-Riba S. Condiciones tempranas del desarrollo y el aprendizaje: el papel de las funciones ejecutivas. Rev Neurol. 2006;S143–51.

154. Sattler JM. Assessment of children: cognitive applications. 4th ed. La Mesa, CA: Jerome Sattler Publisher, Inc.; 2001.

155. Sattler JM. Evaluación infantil: fundamentos cognitivos. 5th ed. Viveros Fuentes S, editor. Padilla Sierra G, Olivares Bari SM, translators. México D.F.: El Manual Moderno; 2010.

156. Schoning F. Problemas de aprendizaje. Carrillo Farga M, translator. México: Trillas; 1990.

157. Secretaría de Salud. Código de Conducta de la Secretaría de Salud [Internet]. México; 2016 Jun 30 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.comeri.salud.gob.mx/descargas/Vigente/2016/Codigo_Conducta.pdf

158. Sellés Nohales P. Estado actual de la evaluación de los predictores y de las habilidades relacionadas con el desarrollo inicial de la lectura. Aula Abierta. 2006;88:53–72.

159. Servera M, Llabres J. Prueba ganadora de la VIII Edición del Premio TEA para la realización de trabajos de investigación y desarrollo sobre tests y otros instrumentos de evaluación: Resumen Manual. CSAT Tarea de Atención Sostenida en la Infancia. Madrid: TEA ediciones; 2004.

160. Servera-Barceló M. Modelo de autorregulación de Barkley aplicado al trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad: una revisión. Rev Neurol. 2005;40(6):358–68.

161. Sociedad Mexicana de Psicología. Código ético del psicólogo. México: Trillas; 2009.

162. Soto Vidal FA, Marques de Figueiredo VL, do Nascimento E. A quarta edição do WISC americano. Aval Psicol. 2011;205–7.

163. Soto-Blanquel M, Ceja-Moreno H, Soto-Mancilla J, Cornejo-Escatell E, Vázquez-Castillo E. Trastorno de déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH) como factor de riesgo de obesidad en escolares de la región de Los Altos de Jalisco. Rev Mex Neurociencia. 2012;13(Suppl 2):S2–3.

164. Sternberg RJ. Investing in creativity: many happy returns. Educ Leadersh. 1995;53(4):80–4.

165. Still GF. Some abnormal psychical conditions in children. Lancet. 1902.

166. Storebø O, Pedersen N, Ramstad E, Kielsholm M, Nielsen S, Krogh H, et al. Methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents – assessment of adverse events in non‐randomised studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012069.pub2

167. Strauss A, Werner H. Disorders of conceptual thinking in the brain-injured child. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1942;96(2):153–72.

168. Styck KM, Watkins MW. Structural validity of the WISC-IV for students with ADHD. J Atten Disord [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Mar 7];21(11):921–8. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1087054714553052

169. Swanson H, Berninger VW. Individual differences in children's working memory and writing skill. J Exp Child Psychol [Internet]. 1996 [cited 2025 Mar 7];63(2):358–85. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1006/jecp.1996.0054

170. Thapar A, Langley K, Asherson P, Gill M. Gene–environment interplay in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the importance of a developmental perspective. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;190(1):1–3.

171. Thapar A, O'Donovan M, Owen M. The genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:275–82.

172. The History of ADHD [Internet]. 2009 Jun 4 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: http://adhdhistory.com/

173. Thome J, Jacobs KA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in a 19th century children’s book. Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19(5):303–6.

174. Thorsen AL, Meza J, Hinshaw S, Lundervold AJ. Processing speed mediates the longitudinal association between ADHD symptoms and preadolescent peer problems. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Mar 7];1–9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02154/full

175. Tulving E. Episodic and semantic memory. In: Tulving E, Donaldson W, editors. Organization of memory. New York: Academic Press; 1972. p. 381–403.

176. Úbeda Cano R, Fuentes Durá I, Dasí Vivó C. Revisión de las formas abreviadas de la Escala de Inteligencia de Weschler para Adultos. Psychol Soc Educ. 2016;8(1):81–92.

177. Unsworth N, Engle R. The nature of individual differences in working memory capacity: active maintenance in primary memory and controlled search from secondary memory. Psychol Rev. 2007;114(1):104–32. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.104

178. Urbano C, Yuni J. Psicología del desarrollo: enfoques y perspectivas del curso vital. Buenos Aires: Brujas; 2005.

179. Valés P, Serrate R. El diagnóstico y tratamiento integrales del TDAH. In: Sipán Compañé A, editor. Educar para la diversidad en el siglo XXI. España: Mira Editores; 2001. p. 357–8.

180. Vázquez-Justo E, Piñon Blanco A, editors. THDA y trastornos asociados. Porto, Portugal: Institute for Local Self-Government Maribor; 2017.

181. Vega Fernández FM. Protocolo de intervención en TDAH. ADHD clinical guidelines in «El Bierzo» Area. Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;11(2):21–35.

182. Vigotsky L. Interacción entre aprendizaje y desarrollo. In: Vigotsky L, Cole M, John-Steiner V, Scribner S, Souberman E, editors. El desarrollo de los procesos psicológicos superiores. 1st ed. Barcelona: Crítica; 1978. p. 123–40.

183. Walg M, Hapfelmeier G, El-Wahsch D, Prior H. The faster internal clock in ADHD is related to lower processing speed: WISC-IV profile analyses and time estimation tasks facilitate the distinction between real ADHD and pseudo-ADHD. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(10):1177–88. doi:10.1007/s00787-017-0971-5

184. Watkins CE, Campbell VL, Nieberding R, Hallmark R. Contemporary practice of psychological assessment by clinical psychologists. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1995;26(1):54–60. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.26.1.54

185. Wechsler D. Intelligence: definition, theory and the IQ. In: Cancro R, editor. Intelligence: genetic and environmental influences. New York: Grune Straton; 1971. p. 319.

186. Wechsler D. Intelligence defined and undefined: A relativistic appraisal. Am Psychol. 1975;30:135–9.

187. Wechsler D. Escala de inteligencia de Wechsler para niños – IV (WISC – IV). Manual técnico y de interpretación. Bloomington, MN: NCS Pearson Inc.; 2003.

188. Wechsler D. Escala Wechsler de inteligencia para niños. Manual de aplicación. Pedraza AA, editor. Sierra GP, translator. México: El Manual Moderno; 2007.

189. Wechsler D. WISC-IV Escala de inteligencia de Wechsler para niños-IV. Manual técnico. 2nd ed. Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 2007.

190. Wesseling E. Visual narrativity in the picture book: Heinrich Hoffmann’s Der Struwwelpeter. Child Lit Educ. 2004 Dec;35(4):319–45.

191. Willcutt EG. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(3):490–9.

192. Woolfolk A. Psicología educativa. México: Prentice Hall; 1999.

193. Zapico Merayo Y, Pelayo Terán JM. Controversias en el TDAH. Cuad Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;11(2):97–115.

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Data curation: José Luis Tornel Avelar, Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá.

Methodology: José Luis Tornel Avelar, Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá.

Software: José Luis Tornel Avelar , Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá.

Drafting - original draft: José Luis Tornel Avelar, Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá.

Writing - proofreading and editing: José Luis Tornel Avelar, Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá.