doi: 10.56294/mw2024483

REVIEW

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Holistic Approach. Parte 1

Trastorno por Déficit de Atención e Hiperactividad: Un Enfoque Integral. Parte 1

José Luis Tornel Avelar1 ![]() *,

Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá1

*,

Leonardo Eleazar Cruz Alcalá1

1Universidad De Guadalajara, Maestría En Ciencias Biomédicas. Jalisco, México.

Cite as: Tornel Avelar JL, Cruz Alcalá LE. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Holistic Approach. Parte 1. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2024; 3:483. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw2024483

Submitted: 01-10-2023 Revised: 21-02-2024 Accepted: 07-05-2024 Published: 08-05-2024

Editor: PhD.

Prof. Estela Morales Peralta ![]()

Corresponding Author: José Luis Tornel Avelar *

ABSTRACT

Introduction: attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) has been widely studied due to its impact on the academic, social and emotional life of those who suffer from it. It was recognized as a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, mainly affecting childhood, although its symptoms persisted into adolescence and adulthood. Since its first descriptions in the 18th century, our understanding of it has evolved significantly, allowing for a more comprehensive approach to its diagnosis and treatment.

Development: historically, ADHD has been conceptualized in different ways, with the research of George F. Still and Barkley standing out in the identification of the disorder. Its diagnosis was based on clinical observation and standardized scales, which generated controversy due to the variability in the presentation of symptoms. Regarding its neurobiological basis, neuroscience studies identified alterations in the prefrontal cortex, the cerebellum and the corpus callosum, while genetic research showed a high heritability of the disorder. Its treatment combined psychological, educational and pharmacological approaches, with methylphenidate standing out as an effective option, although its use required medical supervision.

Conclusions: ADHD represented a challenge in the clinical and educational fields due to its impact on human development. Neuroscience research allowed for a better understanding of its biological and genetic bases, while advances in diagnosis and treatment favored a comprehensive approach. Despite progress, there was a continued need for studies that optimize intervention strategies and promote greater awareness of its impact on patients’ lives.

Keywords: ADHD; Neurodevelopment; Diagnosis; Treatment; Neuroscience.

RESUMEN

Introducción: el Trastorno por Déficit de Atención e Hiperactividad (TDAH) fue ampliamente estudiado debido a su impacto en la vida académica, social y emocional de quienes lo padecen. Se reconoció como un trastorno del neurodesarrollo caracterizado por inatención, hiperactividad e impulsividad, afectando principalmente a la infancia, aunque sus síntomas persistieron en la adolescencia y adultez. Desde sus primeras descripciones en el siglo XVIII, su comprensión evolucionó significativamente, permitiendo un enfoque más integral en su diagnóstico y tratamiento.

Desarrollo: históricamente, el TDAH fue conceptualizado de diversas formas, destacando las investigaciones de George F. Still y Barkley en la identificación del trastorno. Su diagnóstico se basó en la observación clínica y escalas estandarizadas, lo que generó controversias debido a la variabilidad en la presentación de los síntomas. En cuanto a sus bases neurobiológicas, estudios en neurociencia identificaron alteraciones en el córtex prefrontal, el cerebelo y el cuerpo calloso, mientras que la investigación genética evidenció una alta heredabilidad del trastorno. Su tratamiento combinó enfoques psicológicos, educativos y farmacológicos, destacándose el metilfenidato como una opción eficaz, aunque su uso requirió supervisión médica.

Conclusiones: el TDAH representó un desafío en el ámbito clínico y educativo debido a su impacto en el desarrollo humano. La investigación en neurociencia permitió comprender mejor sus bases biológicas y genéticas, mientras que los avances en diagnóstico y tratamiento favorecieron su abordaje integral. A pesar de los progresos, persistió la necesidad de estudios que optimicen las estrategias de intervención y promuevan una mayor concienciación sobre su impacto en la vida de los pacientes.

Palabras clave: TDAH; Neurodesarrollo; Diagnóstico; Tratamiento; Neurociencia.

INTRODUCTION

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most studied neuropsychiatric conditions in the field of psychology and education due to its high prevalence and its impact on the academic, social, and emotional lives of those who suffer from it. It is considered a neurodevelopmental disorder that mainly affects childhood, although its symptoms can persist into adolescence and adulthood. It is characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, significantly interfering with those affected's daily lives.

From an evolutionary perspective, child development comprises a series of biological and neurocognitive transformations that allow children to acquire the necessary skills to interact with their environment. However, any alteration in this process can generate learning and social adaptation difficulties. In this sense, ADHD is one of the main problems affecting children's academic performance and behavior, which has motivated extensive research to understand its origin, diagnosis, and treatment.

Historically, the concept of ADHD has evolved. From the first descriptions in the 18th century to the current definitions included in diagnostic manuals such as DSM-5, there has been a shift from considering hyperactivity as a primary symptom to a broader understanding incorporating deficits in attention and impulse control. Researchers such as George F. Still, in the 20th century, were fundamental in characterizing the disorder. In later decades, advances in neuroscience and psychiatry have allowed a greater understanding of its biological and genetic bases.

The diagnosis of ADHD is not based on laboratory tests but on the clinical observation of symptoms and the application of standardized evaluation scales. This has generated controversy about the validity of the diagnosis, mainly due to the variability in the presentation of symptoms and the differences in the classification criteria used by different diagnostic systems, such as the DSM and the ICD.

The treatment of ADHD is multidisciplinary and includes psychological, educational, and pharmacological interventions. Although stimulants such as methylphenidate are effective in reducing symptoms, their use has been the subject of debate due to possible adverse effects and the need for a comprehensive approach that takes into account the patient's social and emotional context. Intervention strategies include behavioral therapy, psycho-pedagogical support, and modifications in the school and family environment to improve the child's adaptation. Given the impact of ADHD on various areas of human development, its study is essential for formulating effective diagnostic and treatment strategies. The present research addresses its historical evolution, its characteristics, the neurobiological factors that underpin it, and the main intervention strategies to provide a comprehensive view of this disorder.

DEVELOPMENT

Attention deficit disorder

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most studied neuropsychiatric conditions in the field of psychology and education due to its high prevalence and its impact on the academic, social, and emotional lives of those who suffer from it. It is considered a neurodevelopmental disorder that mainly affects childhood, although its symptoms can persist into adolescence and adulthood. It is characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, significantly interfering with those affected's daily lives.

From an evolutionary perspective, child development comprises a series of biological and neurocognitive transformations that allow children to acquire the necessary skills to interact with their environment. However, any alteration in this process can generate learning and social adaptation difficulties. In this sense, ADHD is one of the main problems affecting children's academic performance and behavior, which has motivated extensive research to understand its origin, diagnosis, and treatment.

Historically, the concept of ADHD has evolved. From the first descriptions in the 18th century to the current definitions included in diagnostic manuals such as DSM-5, there has been a shift from considering hyperactivity as a primary symptom to a broader understanding incorporating deficits in attention and impulse control. Researchers such as George F. Still, in the 20th century, were fundamental in characterizing the disorder. In later decades, advances in neuroscience and psychiatry have allowed a greater understanding of its biological and genetic bases.

The diagnosis of ADHD is not based on laboratory tests but on the clinical observation of symptoms and the application of standardized evaluation scales. This has generated controversy about the validity of the diagnosis, mainly due to the variability in the presentation of symptoms and the differences in the classification criteria used by different diagnostic systems, such as the DSM and the ICD.

The treatment of ADHD is multidisciplinary and includes psychological, educational, and pharmacological interventions. Although stimulants such as methylphenidate are effective in reducing symptoms, their use has been the subject of debate due to possible adverse effects and the need for a comprehensive approach that takes into account the patient's social and emotional context. Intervention strategies include behavioral therapy, psycho-pedagogical support, and modifications in the school and family environment to improve the child's adaptation. Given the impact of ADHD on various areas of human development, its study is essential for formulating effective diagnostic and treatment strategies. The present research addresses its historical evolution, its characteristics, the neurobiological factors that underpin it, and the main intervention strategies to provide a comprehensive view of this disorder.

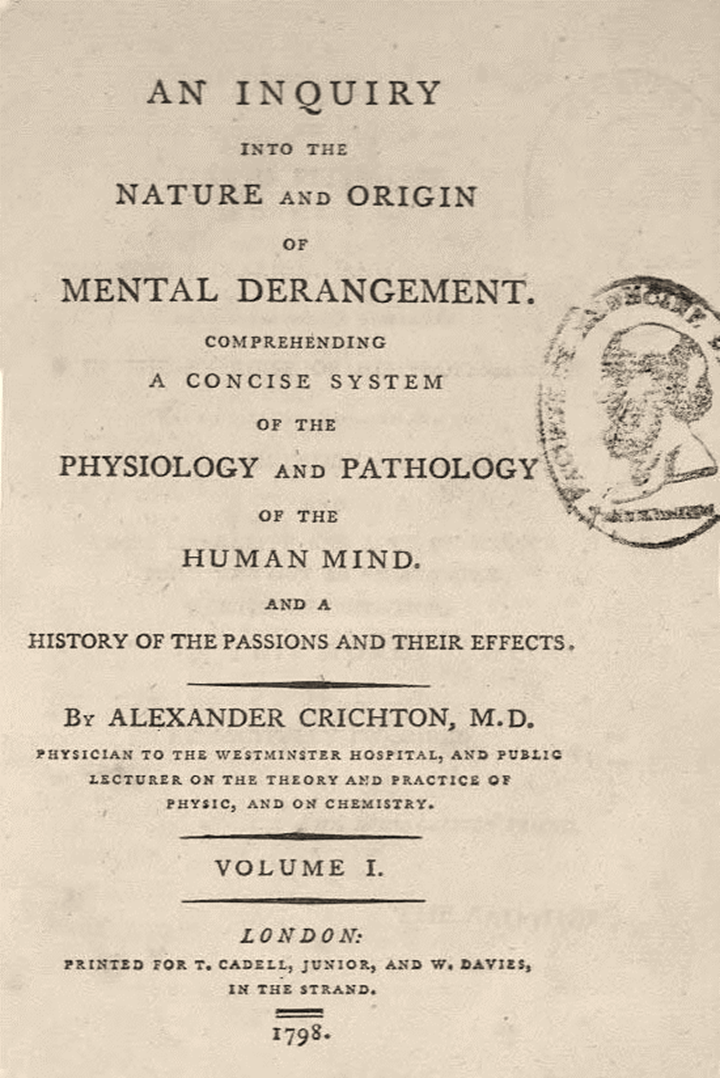

Figure 1. Cover of “An understanding of a concise system of the physiology and pathology of the human mind and a history of the passions and their effects”, (Crichton, 1798)

Other written evidence that we have about the clinical picture is a book published by the German psychiatrist and writer Heinrich Hoffmann in 1845: "Der Struwwelpeter" (Castroviejo, 2009), a children's story consisting of 10 short, illustrated stories, which describes a child with attention deficit and hyperactivity; it is a fascinating case because Hoffmann was one of the first authors to combine the literary conventions of cautionary tales with illustrations (Wesseling, 2004). Some of the problems dealt with in the stories are aggression, antisocial behavior, pyromania, and eating disorders, among others. Additionally, hyperactivity and attention deficit symptoms are dealt with in "The Story of Fidgety Philip,” the first story in the second edition of 1846 of the children's book. One of the illustrations in the book (figure 2) shows a child who cannot sit still at the table despite his parents' instructions (Thome & Jacobs, 2004).

Figure 2. “Fidgety Philip” by Heinrich Hoffmann, 1846

Although the main symptoms of ADHD are represented in the story of "Restless Philip," additional symptoms are described in two other stories. In the story "Johnny Looks Up," symptoms of inattention are mentioned: Johnny loses things necessary for specific tasks, is easily distracted by external stimuli (the sky, clouds, birds), and is careless in the course of daily activities (such as going to school). The progression to antisocial behavior, as the least desirable trajectory for children with ADHD, is described in the story of "Frederick Cruel." It is remarkable how the typical symptoms of ADHD are represented in Hoffmann's book (Thome & Jacobs, 2004).

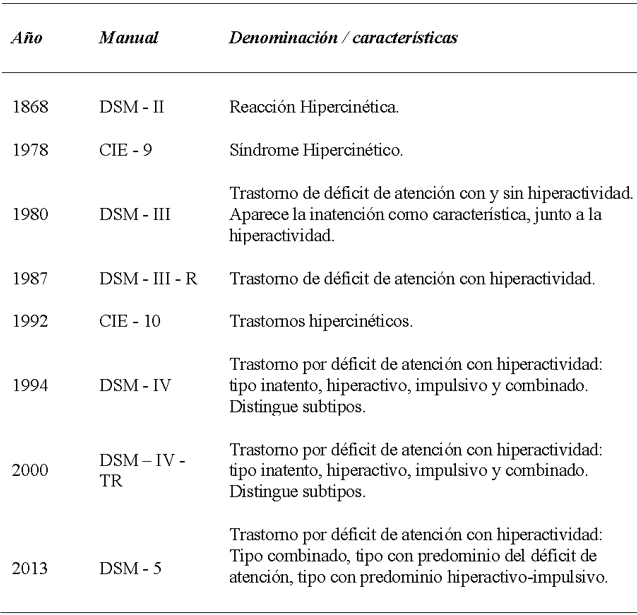

Figure 3. Publication of “Some abnormal psychological conditions in children” by George F. Still (1902))

Now, more than a century later, it was the turn of Sir George Frederick Still, who in a series of lectures in London spoke of a defect in moral behavior: "Children with violent temperaments, uncontrollably unruly, perverse, destructive, unable to pay attention and problematic at school" (Condemarín, Gorostegui, & Milicic, 2005), children' passionate, deviant, resentful and with a lack of impulse control.' In three articles published in The Lancet (1902), the British pediatrician described the clinical characteristics of these subjects as "inhibitory incapacity," "a marked lack of ability to concentrate and sustain attention," and "defects in motor control." Their peculiar behavior and personality, not at all conducive to social conventions, led them to be considered psychiatric patients and, therefore, for many years, they were known as "unstable psychopaths" (Castroviejo, 2009). He speculated in his report that the behavior of these children was the result of a variety of brain injuries. As some children had normal intelligence, he attributed it to "defects in moral control." "Children who show a permanent defect in moral control raise the question of whether it may not be the manifestation of a morbid mental state, but pass for children of normal intellect; it is this particular condition that seems to me to require careful observation and consultation" (Still, 1902). He also observed that the symptoms appeared at a pre-school age (González Garrido & Ramos Loyo, 2006).

Over the following half-century, significant advances and studies in neuroscience and the experience acquired due to the two great wars and their casualties changed the interpretation of the disorder, with hyperactivity being prioritized as the dominant symptom. Hyperactivity became the primary symptom, to the detriment of attention deficit and impulsivity, and in 1950, the disorder changed its name to "Hyperkinetic Syndrome" (Pelayo-Terán, Trabajo-Vega, & Zapico-Merayo, 2012). In 1942, with the publication of Strauss' "Conceptual Thinking Disorders in the Child with Brain Injury," hyperactivity and the tendency to be distracted became of great interest to researchers (Strauss & Werner, 1942). This disorder became known later as "Strauss Syndrome" (Herrera-Narváez, 2005).

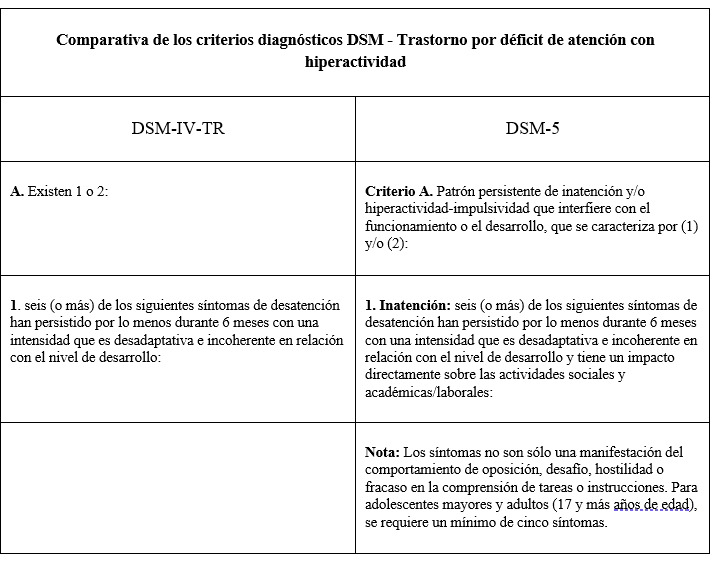

Between the 1960s and 1970s, after observing signs of neurological involvement and the lack of evidence of brain damage, the terms "minimal brain damage" and "minimal brain dysfunction" began to be used, the latter being more functionalist and less organicist than the former (García-Losa, 1997 and Sanfeliu, 2010). In 1966, Clement introduced the term Minimal Brain Dysfunction (MBD) to refer to some delays in psychomotor development with behavioral alterations or deficits in academic performance or some specific motor disorders in some very particular children (Hechtman L., 2000 and American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000, cited in Sell-Salazar, 2003). The review of attention and executive function is personally motivated by the belated experience of observing many children presenting these symptoms in the clinical area (as neuropediatricians) (Rebollo & Montiel, 2006). From the 1960s onwards, multiple definitions began to appear in the specialized literature, as shown in figure 4.

In the 1990s, Barkley (1990) prioritized other aspects of symptomatology and interpreted them as a dysfunction of executive functions, a form of evaluation, and a proposal for treatments different from ADHD (Barkley, DuPaul, & McMurray, 1990). Barkley (1990) proposed the following definition of the disorder:

"ADHD is a developmental disorder characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of attention problems, overactivity, and impulsivity. They usually arise in early childhood, are relatively chronic, and cannot be explained by any major neurological deficit or by other sensory, motor, or speech deficits, nor by the absence of mental retardation or serious emotional disorders. These difficulties are closely related to a difficulty in following "rule-governed behavior" (RGB) and to problems in maintaining a consistent way of working over more or less long periods" (Barkley, 1990) cited in Servera-Barceló, 2005).

Figure 4. Terms in attention deficit disorder diagnostic manuals from 1968 to date

For more than twenty years, there has been an implicit consensus to diagnose ADHD based on deficits in two dimensions of cognitive and behavioral functioning: inattention and motor overactivity/impulsivity (Servera-Barceló, 2005).

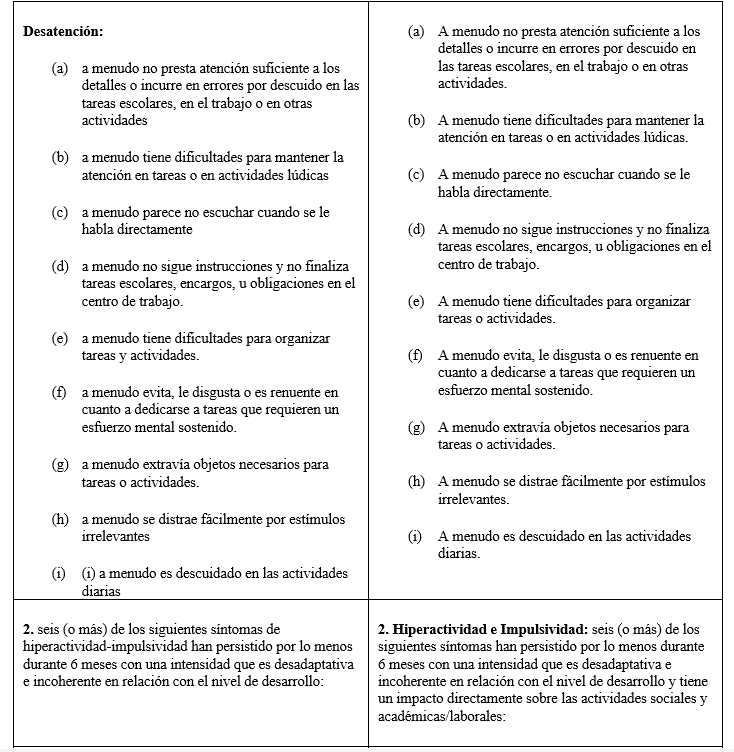

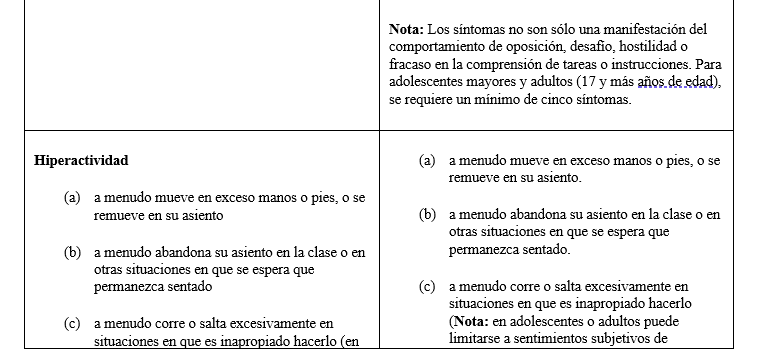

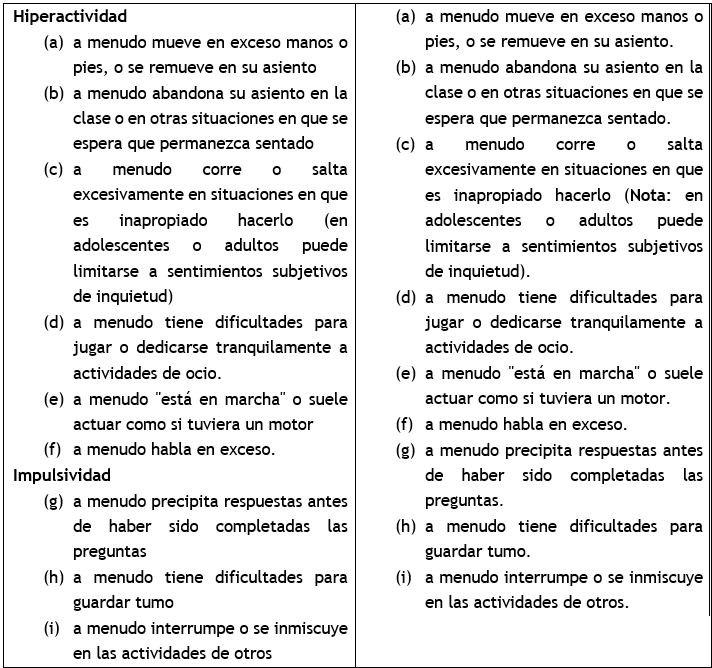

In its most recent update, the APA decided to separate Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder from disruptive behavior disorders and created a group focused on ADHD within neurodevelopmental disorders (Ladrón, Álvarez, Sanz, Muñoz, & Almendro, 2013). Some of the diagnostic criteria for the disorder were also modified (figure 5).

Definition of ADHD

The starting point in the multiple controversies surrounding ADHD is the validity of the concept itself because if the history of ADHD arises from clinical observations and its progressive characterization up to its current definition, on the other hand, the second half of the 20th century, and especially from the 70s onwards, was permeated by opposing opinions, not only from the scientific community but also from public opinion (Zapico Merayo & Pelayo Terán, 2012)

These opinions have remained critical in various fields and have become so intense and persistent that 2002, a consensus of renowned psychiatrists was published in European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2002. They emphasize that, as a matter of science, the notion that ADHD does not exist is simply incorrect; they also recognize the growing evidence of neurological and genetic contributions to ADHD. Moreover, regarding studies on the effectiveness of medication, they highlight the need for treatment of the disorder with multiple therapies in many cases, among other assertions (European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2002).

It is currently believed to be a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects between 5 and 8 % of the child population (Polanczyk, Lima, Horta, Biederman, & Rohde, 2007). It is clinically characterized by the presence of attention deficit, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that are inappropriate from an evolutionary point of view. Attention deficit is defined as difficulty maintaining attention for a certain period. Hyperactivity is excessive motor activity, and impulsivity is the lack of control or inability to inhibit a behavior. The symptoms usually begin in early childhood, are relatively chronic in nature, and cannot be attributed to neurological, sensory, language, mental retardation, or relevant emotional disorders. These difficulties are associated with deficits in rule-governed behavior and a specific pattern of performance (Barkley, 2015).

ADHD is a disorder in its own right with significant repercussions for the person suffering from it and for the people who live with the subject (Vega Fernández, 2012). Barkley (2013), with a more scientific view of the disorder, defines symptomatology as a delay in the appearance of two neuropsychological traits about the appropriate age; the first is inattention, lack of attention, impairments in people's executive function that translates into an inability to adapt to psycho-environmental standards and difficulty in resuming unfinished activities; the second trait is hyperactivity-impulsivity behavior, due to the delay in the inhibitory mechanism of the brain or self-regulation, it is a disinhibitory disorder.

Characteristics of the Disorder

In several studies, this disorder is referred to as " attention deficit syndrome," a condition characterized by a tendency to be easily distracted, difficulty in maintaining attention for a period of time, and a scattered and disorganized personality (Castroviejo, 2009). Thus, we can say that Attention Deficit Disorder with or without Hyperactivity (ADHD) is characterized by a decrease in attention and behavior with hyperactivity and excessive and inappropriate impulsivity in some cases, in short. However, it is necessary to go into greater depth on each disorder's characteristics, highlighting the many studies on the subject.

Attention deficit disorder affects preschoolers, schoolchildren, adolescents, and adults of both genders, regardless of social status, race, religion, or socioeconomic background (De la Peña, Palacio, & Barragán, 2010). Behavioral manifestations occur in multiple contexts, including home, school, work, and social (Cidoncha Delgado, 2010).

In addition to the forms of renunciation of learning and academic development, the child is more or less aware of his lack of effort and his lack of interest, as well as the problems of intellectual inhibition, which the child suffers from not being able to dedicate himself to and carry out school activities. He tries to work, he tries hard, but he fails, feeling intellectually blocked (Ajuriaguerra, 2002). Furthermore, children with this disorder present alterations on three levels: academic, behavioral, and emotional (Cidoncha Delgado, 2010), which make their social adaptation difficult.

It is for this reason that subjects with ADHD may achieve lower academic and professional levels than those obtained by their peers. Their intellectual development, as evaluated by IQ tests, is lower than that of other children (American Psychiatric Association, 2002). In groups of subjects with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, it has been observed that specific tests that require persistent mental processing show anomalous performance compared to control subjects (American Psychiatric Association, 2002). One cannot expect a child to operate successfully in a school environment if he or she shows inattention.

According to Rodríguez-Salinas et al. (2006), 25-30 % of children with ADHD have a specific learning disorder in areas such as reading, writing, mathematics, and even motor coordination, and 50 % of children may have language disorders in expression and reception, in fluency, in pragmatic language, prosody, and articulation, in addition to having problems with working memory, planning and organization (Daley & Birchwood, 2009).

Due to difficulties in learning and applying knowledge (low grades and test scores, poor academic performance, including completing class work or homework), in terms of social participation, ADHD can compromise the integral development of the child, including the generation of restrictions in educational levels and professional training, and possibly school dropout (Loe & Feldman, 2007) and, although it manifests itself from childhood, it has a chronic course with expressions throughout life and in up to 60 % of cases it can continue into adulthood (De la Peña, Palacio, & Barragán, 2010).

In summary, it is necessary to recognize that ADHD is among the leading mental health problems affecting children, adolescents, and adults; the condition is of biological origin, with psychosocial elements playing a role in its expression. It is also scientifically recognized worldwide and has severe implications for the family, school, work, and socioeconomic functioning of individuals who suffer from it, as it increases the risk of accidents, school failure, and problems with self-esteem and is related to greater consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit substances, job instability and failure in relationships (De la Peña, Palacio, & Barragán, 2010).

Neurobiological aspects and etiopathogenesis

"Whatever may be the cause of each of the slight differences between the offspring and their parents - and there must be a cause for each of them - we have reason to believe that the continuous accumulation of favorable differences has been the origin of all the most important modifications of structure about the habits of each species" (Darwin, 1921, p.161)

The study of the etiological and physiopathological factors related to ADHD is one of the emerging topics in the current scientific literature (Duñó Ambrós, 2015). The etiology responds to diverse causal factors, which determine a neurobiological vulnerability that, interacting with other risk factors, gives rise to the clinical picture that characterizes the disorder (Duñó Ambrós, 2015).

Among the studies and scientific research related to the etiology of the disorder, there are various topics such as dietary, biochemical, genetic, relationships with syndromes, smoking, alcoholism or drugs during conception and pregnancy, and adoption, to mention a few (Quintero Gutiérrez del Alamo, Rodríguez-Quirós, Correas, & Pérez-Templado, 2009, Fernández-Jaén, Fernández-Mayoralas, Calleja-Pérez, Muñoz-Jareño, & López-Arribas, 2012, Martínez-Levy, et al., 2013, Martínez, et al., 2015). The most significant risk factor for suffering from ADHD is that one of the biological parents has the disorder (Pérez Hernández & Corrochano Ovejero, 2016).

Genetic factors

Although the contribution and modulation of socio-environmental factors cannot be ruled out, ADHD has a biological basis (De la Osa Langreo, Mulas, Mattos, & Gandía Benetó, 2007). A substantial genetic contribution to the development of ADHD has been demonstrated. In this sense, the empirical evidence demonstrates a certain degree of familial transmission, which reaches an estimated heritability of between 55 % and 78 % (Wilens & Spencer, 2010).

The familial risk appears to be higher among relatives of people with ADHD and conduct disorders. Twin and adoption studies have provided strong evidence that genetic factors contribute to the etiology of the disorder, with heritability estimates of 60-91 % (Thapar, O'DonovanO'Donovan, & Owen, 2005).

Suppose genetic factors contribute to the etiology and genes with susceptibility interact with environmental risk factors in complex ways. In that case, the same risk factors that influence the origins of ADHD may play a role in the development of the disorder. However, it is also possible that a different set of risk and protective factors influences the course and outcome of the disorder (Thapar, Langley, Asherson, & Gill, 2006).

This information indicates that we are dealing with a type of multifactorial polygenic inheritance, depending on diverse environmental factors, among which perinatal circumstances and possibly methods of upbringing and education are found (Cardo & Severa, 2008). It is important to recognize the phenotypic complexity of ADHD, to recognize that it is a developmental disorder that shows continuity and change in clinical presentation over time, which is influenced by biological and psychosocial environmental risk factors (Thapar, Langley, Asherson, & Gill, 2006). Based on this, about the etiological investigation of the disorder, there is no doubt that significant progress has been made; however, it is gradual.

However, let us leave aside environmental factors such as diet, upbringing, and education, among others, even though they are important modulators in the expression of the disorder. They do not present causal evidence. Similarly, in genetic studies, could we point to the current conditions of a specific gene? The dopamine type 2 gene and DATI (dopamine transporter gene) showed some involvement in the early 1990s, which was not finally confirmed. Recently, other dopamine-related genes, DRD4 and DRD5, have shown more interesting relationships, although the results cannot be shown as definitive (Servera-Barceló, 2005).

In a study of genetic variability in individuals living in Mexico City, it was shown that in the Caucasian population, the risk alleles reported for psychiatric disorders such as ADHD are 7R of the DRD4 gene and 10R of the DAT1 gene was higher in the Mexican population (Martínez-Levy et al., 2013).

Neurophysiology

Similarly, neurophysiology has provided results of great interest, although not definitive either. Children with ADHD have alterations in brain anatomy and neurophysiology (De la Osa Langreo, Mulas, Mattos, & Gandía Benetó, 2007). In the 80s, the first neuroimaging findings, initially with computerized axial tomography, which would progressively be replaced by magnetic resonance and functional imaging tests, revealed the involvement of different brain circuits (Pelayo-Terán, Trabajo-Vega, & Zapico-Merayo, 2012). Servera-Barceló (2005) points out that we now know that, contrary to what their behavior might suggest, children with ADHD have generalized cortical hypo-activation. They also present, at least in a significant percentage of cases, a decrease in the structural volume of the right prefrontal cortex, the striatum, the corpus callosum, and the right cerebellum, and the same areas, with some frequency, lower electrical activity, lower blood flow and an alteration in the availability of dopamine and noradrenaline have been detected. However, in the majority of cases, neuroimaging techniques do not detect any relevant problem in children with ADHD, and much of the evidence of biochemical dysfunction is due to indirect data (good response to drugs) (Servera-Barceló, 2005).

Previous studies have identified several neurocognitive pathways for ADHD, which are well-founded in neuroscience (Castellanos & Tannock, 2002). These pathways involved a specific abnormality in reward-related circuits related to abnormalities in the (ventral) frontostriatal brain areas, a deficit in the temporal processing of the basal ganglia and cerebellum, and deficits in working memory related to abnormalities in frontostriatal (dorsal) areas (Castellanos & Tannock, 2002; Bergwerff, Luman, Weeda, & Oosterlaan, 2017).

Despite the scientific evidence about the disease's neurobiological characteristics, which supports the use of medication for its treatment, this condition continues to generate controversy regarding its existence, persistence throughout life, and optimal treatment (Palacios–Cruz et al., 2011).

Epidemiology

Winitzer (1999) estimates that ADHD is diagnosed in around 50 % of children who attend psychiatrists and pediatric neurologists and that it affects between 1,7 % and 16 % of the school-age population, depending on the group studied. The diagnostic methods used (González Garrido & Ramos Loyo, 2006).

Palacios-Cruz (2011) mentions that the prevalence of ADHD worldwide is high. Epidemiological studies show that 3 to 5 % of school-age children and adolescents can be diagnosed with it (Palacios–Cruz et al., 2011). Currently, an estimated 6,4 million children are diagnosed with ADHD (Hancock, 2017).

In recent decades, researchers worldwide have conducted studies to define the prevalence of the disease. Several reviews of the literature have reported highly variable rates worldwide, ranging from a minimum of 1 % to a maximum of almost 20 % among school-age children, although the reasons for the variability between studies remain poorly understood (Polanczyk, Lima, Horta, Biederman, & Rohde, 2007).

The Latin American League for the Study of ADHD (LILAPETDAH, 2010) stated that the average global prevalence of ADHD is 5,29 %. In Latin America, there are at least 36 million people with ADHD, and less than a quarter of patients are under multimodal treatment; among these, only 23 % have psychosocial therapeutic support, and only 7 % have adequate pharmacological treatment (De la Peña, Palacio, & Barragán, 2010).

In Mexico, it is estimated that there are approximately 33 million children and adolescents, of which 1,5 million could be diagnosed with ADHD. In terms of the clinical context, at least 30 % of patients who come for a first assessment in child psychiatry services present problems of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity (Palacios–Cruz et al., 2011). In addition to this, reports on the use of health services in our country show that it can take patients between 8 and 15 years to seek specialized care and that 15 % of people with mental disorders resort to self-medication (Palacios-Cruz et al., 2011).

It was previously mentioned that if it is not treated, ADHD implies a significantly higher risk of academic failure, as well as other problems in adulthood. It constitutes an important risk factor for the exacerbation of diseases that produce dependency, that is to say addictions associated with the use and abuse of substances such as alcohol and drugs (Ohlmeier et al., 2009), the development of psychiatric disorders, as well as the development of antisocial and illicit behaviors (dissocial and even criminal behavior) (Aguilar Cárceles & Morillas Cueva, 2014) and labor problems (Aragonés Benaiges, Piñol, Cañisá, & Caballero, 2013). Faced with these diagnostic and therapeutic problems, specific strategies must be developed to restore the health and well-being of the affected subjects.

Moreover, the current concept of health has incorporated the need to diagnose and intervene as early as possible in order to prevent any risk factor or situation that could alter the biopsychosocial well-being of the individual (Sastre-Riba, 2006).

Diagnosis and treatment

In the Mexico Declaration for ADHD in Latin America, carried out in Mexico City on June 17 and 18, 2007, in the 1st Latin American Consensus on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, it was declared that both the diagnosis and the treatment should be in line with the socioeconomic and cultural reality of those living in each of the Latin American countries and that it is essential to ensure medical care for the child, adolescent or adult with ADHD with or without comorbidity and to offer interdisciplinary treatment, as well as adequate follow-up and monitoring. It was also stated that pharmacological treatment should be prescribed and monitored exclusively by doctors, and the decision to accept pharmacological treatment should be the shared responsibility of parents, the patient, and the doctor (Barragán Pérez & De la Peña, 2008).

No laboratory or cabinet tests are required to establish the diagnosis of ADHD (De la Peña, Palacio, & Barragán, 2010). However, it is essential to establish an appropriate diagnosis and to initiate comprehensive treatment early (González Garrido & Ramos Loyo, 2006; Thapar, Langley, Asherson, & Gill, 2006).

ADHD evaluations are accompanied by implementing scales, which are applied according to the patients' ages. The use of validated scales for ADHD is recommended for an objective evaluation of symptomatic severity (Gorga, 2013).

It should be noted that the diagnosis is made through the medical history. Neuropsychological tests are not essential for diagnosis, but they are a helpful complement that allows for objective monitoring, playing an important role in the diagnosis and development of specialized interventions, as they allow for the identification of both the deficits and the strengths that children present in various areas (Álvarez-Arboleda, Rodríguez-Arocho, & Moreno-Torres, 2003). The positive results of these tests are not always specific to ADHD, as they measure impulsivity and inattention of many origins. Neuropsychological evaluation is used more to provide detailed information about the cognitive and behavioral profile of the subjects evaluated (Álvarez-Arboleda, Rodríguez-Arocho, & Moreno-Torres, 2003).

The treatment of ADHD should be comprehensive, personalized, multidisciplinary, and according to each patient's specific needs and characteristics (Valés & Serrate, 2001). After an adequate diagnosis, the available therapeutic alternatives should be considered; these include psychosocial and psychopharmacological management measures (Palacio, De la Peña, Palacios-Cruz, & Ortiz-León, 2009).

A randomized clinical trial showed that behavioral treatment focused on homework problems benefits children's homework completion and accuracy. In contrast, long-acting stimulant medication resulted in limited and non-significant acute effects (Merrill et al., 2017).

One of the main contributions to the early treatment of learning difficulties is considering them from a developmental perspective. This approach will enable them to be identified in the early stages of development and thus provide treatment in an interdisciplinary manner at an ideal time to try to reorganize and improve deficient functions (Millá, 2006). It is pertinent to highlight that the problems we encounter in the psychological analysis of teaching cannot be correctly resolved or even formulated without situating the relationship between learning and development in school-age children (Vygotsky, 1978).

In a critical review of ADHD treatment guides, it was indicated that multimodal treatment is ideal for the comprehensive management of ADHD (Rabito Alcón & Correas, 2014). Pharmacotherapy remains the first-line treatment throughout life, precisely stimulant medication. Among these, methylphenidate treatment stands out, and all agree that psychological therapy increases the effectiveness of the treatment as an adjunct to pharmacological treatment (Rabito Alcón & Correas, 2014). However, this effectiveness is reduced when it comes to children with ADHD with severe behavior and emotional problems, as perceived by parents, especially emotional dysregulation and emotional lability (Duñó Ambrós, 2015). Some have concluded that methylphenidate may be associated with several serious adverse events, although the evidence for non-comparative studies is low (Storebø et al., 2018). However, most studies provide the most convincing evidence on the long-term benefits of methylphenidate, important distal outcomes, not only symptom control, but also the reduction of comorbid depression, substance use, and dependence, among others (Chang, D'Onofrio, Quinn, Lichtenstein, & Larsson, 2016) (Gerlach, Banaschewski, Coghill, Rohde, & Romanos, 2017).

Something similar happens with atomoxetine, however, it shows efficacy in improving ADHD symptoms in children and adults (Clemow, Bushe, Mancini, Ossipov, & Upadhyaya, 2017) without associated comorbidities (Oliveira, et al., 2017). However, the effectiveness of this treatment has a slow onset and it can take up to 8-12 weeks to achieve an optimal effect (Vázquez-Justo & Piñon Blanco, 2017).

ADHD is a disorder with cognitive and affective alterations, both motivational and emotional. It is known that the brains of people with ADHD do not produce the same amount of dopamine as people without the disorder, which underlies motivational and emotional dysfunctions (Gaxiola Gaxiola, 2015). Because of this, it is recommended that any integrative process for treatment should broaden knowledge about the specific difficulties of emotional regulation.

It is important to mention that the psychopathology of children and adolescents presents a series of peculiarities that differentiate it significantly from that of adults (Pascual Lema, 2012). The ways in which they fall ill and manifest the clinical picture do not coincide in many cases with the symptoms defined in adults. In fact, the stages of evolutionary development can condition the criteria of normality or illness (Pascual Lema, 2012).

There are different tools for developing the emotional skills of children in the field of educational psychology. It is recommended that techniques for behavior modification, cognitive-behavioral techniques, academic adaptations and social skills be included (Presentación Herrero, Siegenthaler Hierro, Jara Jiménez, & Casas, 2010). Other studies also support the need to carry out intervention programs on executive functions (Pérez Mariño, 2015).

To conclude this section, we will emphasize that neuropsychological exploration in children and adolescents with ADHD is useful for understanding the profile of skills and difficulties in cognitive functioning and comorbidity with specific learning disorders (Fernández-Mayoralas, Fernández-Perrone, & Fernández-Jaén, 2013).

Attention Deficit Criteria in Diagnostic Manuals of Mental Disorders

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th ed. DSM-5

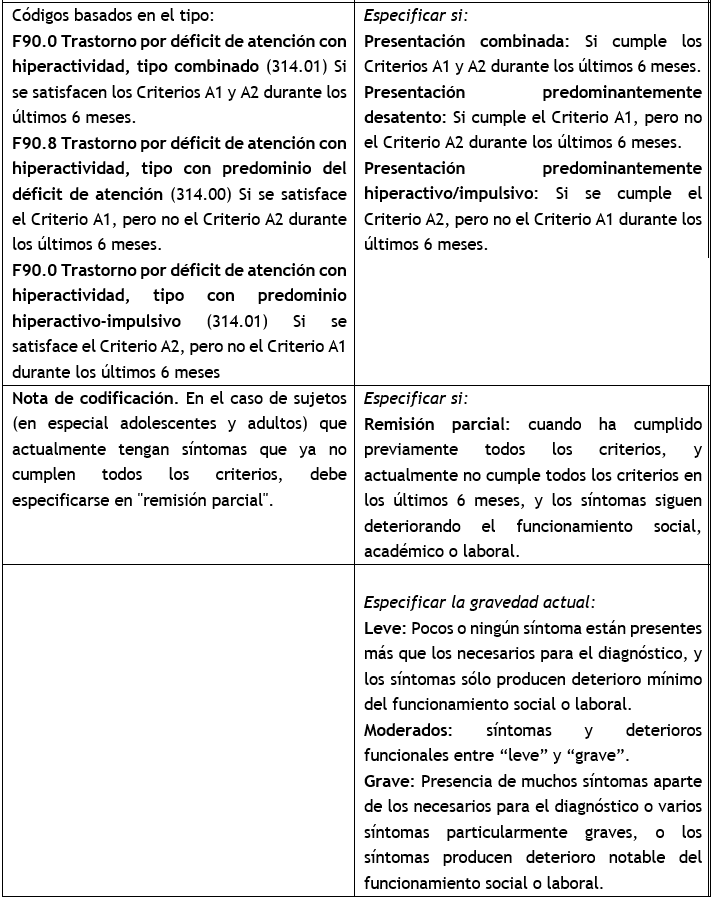

As the DSM-5 points out, the main characteristics of ADHD are inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that affect development, categorized as shown in figure 5 below.

Figure 5. Comparison of DSM diagnostic criteria (pp. 17-20) (Ladrón, Álvarez, Sanz, Muñoz, & Almendro, 2013)

Suppose one looks closely at the current DSM-5 criteria. In that case, the following peculiarity is identified: in Criterion D, it is specified that the symptoms "Interfere with" or, as in other translations, "reduce the quality of" the patient's performance (p. 60), unlike almost all the different diagnostic criteria described in the manual, which specify "the dysfunction" for performance (Morrison, 2015). Perhaps due to social inclusion policies, avoiding labeling the subject as disabled, however, could significantly reduce the specificity of the ADHD diagnosis, basing the criteria on the presence of symptoms and not fully demonstrating a disability.

Other widely used classification systems differ from this categorization. On the one hand, both the DSM-IV-TR and the ICD-10 include inattention and hyperactivity under the heading of behavioral disorders. At the same time, the French classification (CFTMEA-R) considers that attention disorders with and without hyperactivity belong to different categories of behavior (behavioral disorders and cognitive disorders, respectively).

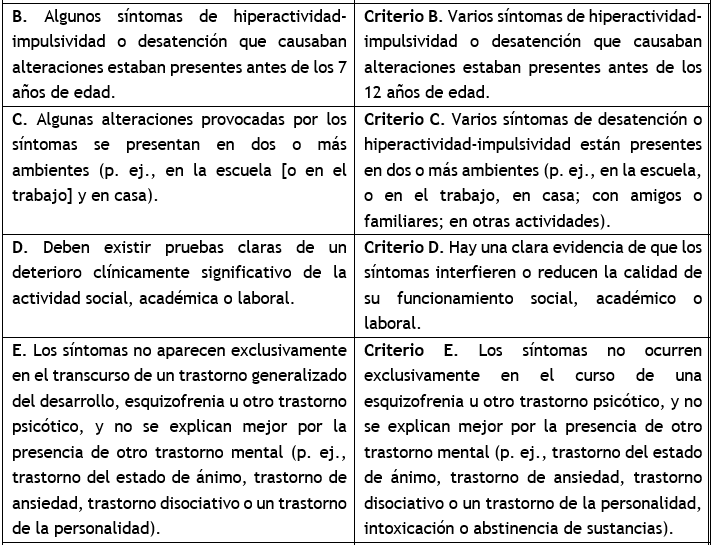

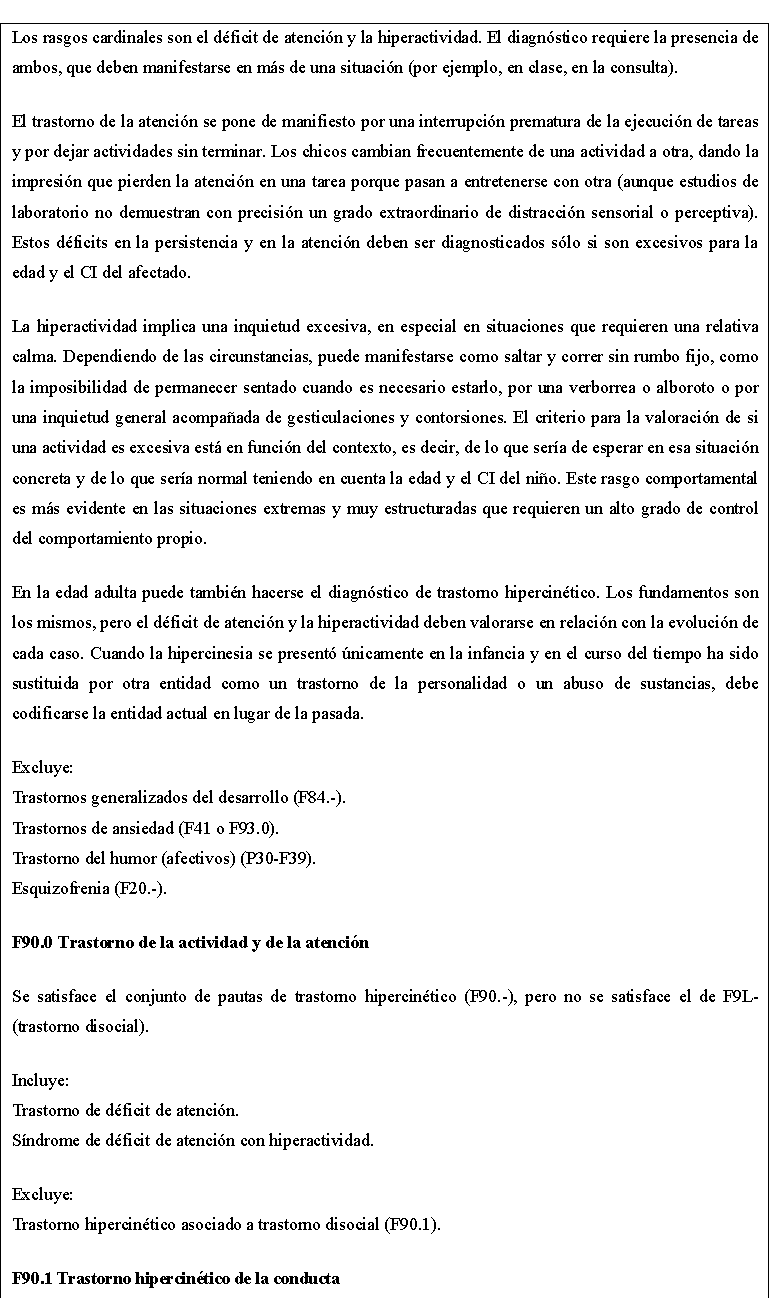

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th revision. ICD-10

The ICD-10 in its section F90. Hyperkinetic disorders within the classification of Emotional and behavioral disorders that usually appear in childhood and adolescence (F90–F98) indicate that the main characteristics of ADHD are a lack of persistence in activities that require the participation of cognitive processes and the tendency to change from one activity to another without finishing any of them, together with disorganized, poorly regulated and excessive activity. It also indicates that there is often a cognitive deficit and specific delays in motor and language development, as well as reading or learning problems (PAHO, 1996). Figure 6 specifies the ADHD assessment criteria considered by the ICD-10 for diagnosis.

Figure 6. ADHD assessment criteria considered by the ICD-10 for diagnosis

It is essential to point out that ICD-10 does not include the term ADHD Predominantly Inattentive, containing only Attention Deficit and Activity Disorder, which corresponds to the combined and hyperactive-impulsive subtype of ADHD in the DSM. In addition, attention deficit without hyperactivity is not accepted in the category of Hyperkinetic Disorders, not even as others (F 90,8) or Unspecified (F 90,9). Still, it is included in Other Specified Emotion and Behavior Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence (F 98,8), together with Onychophagia, Rhinodactylomania, Thumb Sucking, and Excessive Masturbation.

These differences in the ICD-10 classification are justified by the fact that there is insufficient empirical validation of attention deficit, as it is a psychological process about which little is known. Furthermore, many of these children show other symptoms that are not included, in the same way, that other children do not meet the diagnostic criteria in two environments, so the mistake could be made of including children with anxiety, apathy, and other problems of a different nature (Jara Segura, 2009). Because of this, it is considered necessary for children with these symptoms to be diagnosed in appropriate categories (WHO, 1992; 2000).

The World Health Organization is developing the eleventh revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11), which is planned for publication in 2017 (Cochran et al., 2014).

French Classification of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (CFTMEA-R)

In the French Classification, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders are included in category number 7: Disorders of Conduct and Behavior, which forces the clinician to question the meaning of these disorders, investigating, first of all, the presence of an underlying pathology that would imply the classification of the subject in one of the first four categories of AXIS 1. In that case, ADHD would appear as a complementary category. Only when the behavioral syndrome, ADHD in this case, is sufficient to delimit the clinical framework is it coded as the primary diagnosis? Otherwise, it is comparable in specifications to ICD-10, except that the category Dissocial Hyperkinetic Disorder (F 90,1) does not exist.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in the Altos Region

In the state of Jalisco, in a study by Barrios and other collaborators (2016), they estimated the prevalence of ADHD at 8,9 % in the school population of the city of Guadalajara, according to the parents' report in 4399 questionnaires applied to them.

An increase in the prevalence of this disorder in the Altos Sur area of the State of Jalisco has been documented. In 2008, research carried out on children in the first and second grades of primary schools in the cities of Jalostotitlán, Tepatitlán de Morelos, and San Miguel El Alto was studied. The results showed a prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in 14,6 % of the children studied (Cruz et al., 2010), which demonstrates a growing and alarming situation.

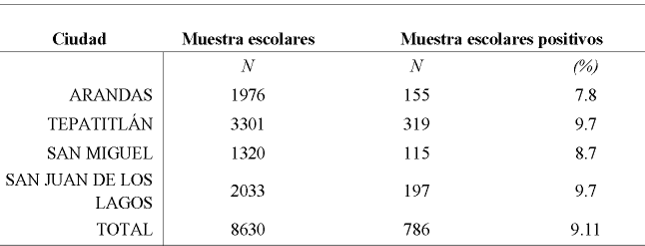

Another study carried out in the cities of Tepatitlán de Morelos, San Miguel El Alto, Arandas, and San Juan de los Lagos, with the support of the pediatric neurology service of the "Fray Antonio Alcalde" Civil Hospital, which, in addition to confirming the diagnosis of ADHD, the aim was to document other pathological comorbidities such as fine motor deficiencies and language disorders, among others (Cornejo, Fajardo, López, Soto, & Ceja, 2015). The results obtained show a high prevalence of the disorder in the city of Tepatitlán (9,7 %) compared to the statistics of the other nearby towns (x = 9,1 %), as shown in figure 7 below.

Figure 7. Prevalence of ADHD in schoolchildren in northeast Jalisco (Cornejo, Fajardo, López, Soto, & Ceja, 2015)

In addition, although this is not research into eating behavior, it is considered essential to point out that a study presented at the 36th Annual Meeting of the Mexican Academy of Neurology concluded that the prevalence of obesity was higher in schoolchildren with ADHD in the Altos region than in the rest of the school population in the state of Jalisco (Soto-Blanquel, Ceja-Moreno, Soto-Mancilla, Cornejo-Escatell, & Vázquez-Castillo, 2012) so that already latent comorbidity of the disorder in the region can be identified. Based on this health statistics information, it can be concluded that there is a significant problem, with a considerable prevalence, that needs attention.

Final notes on ADHD

According to Barkley (2012), professor of Neurology and Psychiatry at the University of South Carolina and a world leader in research on the disorder, current studies show that the term ADHD is limited, as it goes beyond the characteristics of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity:

“ADHD involves a deficit in self-control or, some professionals call, executive functions, which are essential for planning, organizing, and carrying out complex human behaviors over long periods. That is to say, in children with ADHD, the “executive” part of the brain, which supposedly organizes and controls behavior by helping the child to plan future actions and follow through with the established plan, functions in an ineffective manner” (Barkley R. A., 2012, p.165).

Current approaches argue that ADHD is a diagnostic construct that refers to the inadequate functioning and development of these functions (Barkley, 2012). According to this approach, people with ADHD cannot activate and sustain those functions responsible for the self-regulation of behavior.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neuropsychiatric condition that has been widely studied due to its impact on multiple aspects of human development. From a historical perspective, the understanding of ADHD has evolved significantly from being considered a behavioral problem to a neurodevelopmental disorder with well-documented biological and genetic bases. Researchers such as George F. Still and Barkley have been fundamental in identifying and characterizing this disorder, contributing to its recognition in the main diagnostic manuals such as the DSM and the ICD.

ADHD affects a significant proportion of the child population and can persist into adolescence and adulthood, causing difficulties in academic performance, social adaptation, and emotional functioning. Children with ADHD present symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that interfere with their daily life and can compromise their academic and social development. In addition, the disorder is associated with a greater predisposition to behavioral problems, emotional disorders, and difficulties in adult life, such as job instability and problems in interpersonal relationships.

Advances in neuroscience have made it possible to identify alterations in brain structures such as the prefrontal cortex, the corpus callosum, and the cerebellum, which supports the hypothesis that ADHD has a biological basis. Likewise, genetic studies have demonstrated the disorder has a high heritability, indicating that genetic factors play a fundamental role in its manifestation. However, interaction with environmental factors, such as the family and school environment, also influences the expression and severity of the symptoms.

Diagnosis is based on clinical observation and the application of standardized assessment scales, although the variability in the presentation of symptoms has generated controversy regarding its validity. Trained professionals must make the diagnosis to avoid errors that can lead to over-diagnosis or misdiagnosis.

The treatment of ADHD is multidisciplinary and includes psychological, educational, and pharmacological interventions. The use of stimulants such as methylphenidate is effective in reducing symptoms, although their administration must be carefully supervised due to possible adverse effects. Behavioral and psycho-educational strategies, together with adapting the school and family environment, play a crucial role in improving patients' quality of life.

Finally, it is essential to continue promoting research into ADHD to improve diagnosis and treatment strategies and raise awareness of the importance of early intervention. Given its impact on various areas of development, the study of ADHD is essential to guarantee a better prognosis and well-being for those who suffer from it.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Adalio CJ, Owens EB, McBurnett K, Hinshaw SP, Pfiffne LJ. Processing Speed Predicts Behavioral Treatment Outcomes in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Predominantly Inattentive Type. J Abnorm Child Psychol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Mar 7];46(4):701–11. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10802-017-0336-z

2. Aguilar Cárceles MM, Morillas Cueva L. El trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH): aspectos jurídico-penales, psicológicos y criminológicos. Madrid: Dykinson; 2014.

3. Ajuriaguerra J. Manual de psiquiatría infantil. 4th ed. Barcelona: Masson; 2002.

4. Álvarez-Arboleda LM, Rodríguez-Arocho WC, Moreno-Torres MA. Evaluación neurocognoscitiva de Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad. Perspect Psicol. 2003;85–92.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales. Barcelona: Masson; 2002.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. American Psychological Association. APA Diccionario Conciso de Psicología. México: Manual Moderno; 2010.

8. American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of Psychologists and Code of conduct [Internet]. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/principles.pdf

9. Anastasi A, Urbina S. Tests psicológicos. 7th ed. Ortíz Salinas ME, translator. México: Prentice Hall; 1998.

10. Anderson JR. Aprendizaje y memoria. Un enfoque integral. 2nd ed. México D.F.: McGraw-Hill/Interamericana; 2001.

11. Andrés-Pueyo A, Colom R. El estudio de la inteligencia humana: recapitulación ante el cambio de milenio. Psicothema. 1999;11(3):453–76.

12. Antshel KM, Faraone SV, Stallone K, Nave A, Kaufmann FA, Doyle A, et al. Is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder a valid diagnosis in the presence of high IQ? Results from the MGH Longitudinal Family Studies of ADHD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;687–94. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01735.x

13. Aragón EL. Evaluación Psicológica: Historia, fundamentos teórico-conceptuales y psicometría. Tovar Sosa MA, editor. México: El Manual Moderno; 2011.

14. Aragón LE, Silva A. Evaluación psicológica en el área educativa. 1st ed. México: Pax México; 2002.

15. Aragonés Benaiges E, Piñol JL, Cañisá A, Caballero A. Cribado para el trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad en pacientes adultos de atención primaria. Rev Neurol. 2013;56(9):449–55.

16. Ardila A, Rosselli M, Villaseñor EM. Neuropsicología de los trastornos del aprendizaje. 1st ed. México D.F.: Manual Moderno; 2005.

17. Baddeley A. Working memory. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci [Internet]. 1983 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Mar 7];302(1110):311–24. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2395996

18. Barkley RA. Distinguishing Sluggish Cognitive Tempo From ADHD in Children and Adolescents: Executive Functioning, Impairment, and Comorbidity. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2025 Mar 7];161–73. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.734259

19. Barkley RA. La importancia de las emociones. XI Jornada sobre Déficit de Atención e Hiperactividad. TDAH: UNA EVIDENCIA CIENTÍFICA [Internet]. Madrid, España; 2013 Dic 11 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.educacionactiva.com/

20. Barkley RA. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. 4th ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015.

21. Barkley RA, Peters H. The earliest reference to ADHD in the medical literature? Melchior Adam Weikard's description in 1775 of "attention deficit" (Mangel der Aufmerksamkeit, Attentio Volubilis). J Atten Disord. 2012;16(8):623–30. doi:10.1177/1087054711432309

22. Barkley RA, DuPaul GJ, McMurray MB. Comprehensive evaluation of attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity as defined by research criteria. J Consult Clin Psychol [Internet]. 1990 [cited 2025 Mar 7];58(6):775–89. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.775

23. Barragán Pérez E, De la Peña F. Primer Consenso Latinoamericano y declaración de México para el trastorno de déficit de atención e hiperactividad en Latinoamérica. Rev Med Hondur. 2008;76(1):33–8.

24. Barrios O, Matute E, Ramírez-Dueñas M, Chamorro Y, Trejo S, Bolaños L. Características del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad en escolares mexicanos de acuerdo con la percepción de los padres. Suma Psicol [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 Mar 7];23(2):101–8. doi:10.1016/j.sumpsi.2016.05.001

25. Bergwerff CE, Luman M, Weeda WD, Oosterlaan J. Neurocognitive profiles in children with ADHD and their predictive value for functional outcomes. J Atten Disord. 2017;1–11. doi:10.1177/1087054716688533

26. Bohórquez Montoya LF, Cabal Álvarez MA, Quijano Martínez MC. La comprensión verbal y la lectura en niños con y sin retraso lector. Pensam Psicol. 2014;12(1):169–82. doi:10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI12-1.cvln

27. Brennan JF. Historia y sistemas de la psicología. 5th ed. Dávila Martínez JF, translator. México: Prentice Hall; 1999.

28. Bridgett DJ, Walker ME. Intellectual functioning in adults with ADHD: A meta-analytic examination of full scale IQ differences between adults with and without ADHD. Psychol Assess [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2025 Mar 7];18(1):1–14. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.1

29. Brown TE. Comorbilidad del TDAH. Manual de las complicaciones del trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad en niños y adultos. 2nd ed. Barcelona, España: Masson; 2010.

30. Bruning R, Schraw G, Norby M. Psicología cognitiva y de la instrucción. 5th ed. Martín Cordero JI, Luzón Encabo JM, Martín Blecua E, translators. Madrid, España: Pearson Educación; 2012.

31. Burgaleta Díaz DM. Velocidad de procesamiento, eficiencia cognitiva e integridad de la materia blanca: Un análisis de imagen por tensor de difusión [doctoral thesis]. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Facultad de Psicología; 2011.

32. Bustillo M, Servera M. Análisis del patrón de rendimiento de una muestra de niños con TDAH en el WISC-IV. Rev Psicol Clín Niños Adolesc. 2015 Jul;2(2):121–8.

33. Cantero Caja A. Nueva Comercialización del WISC-IV [Internet]. 2011 Dec [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: Dialnet-NuevaComercializacionDelWISCIV-3800737.pdf

34. Cardo E, Servera M. Trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad: estado de la cuestión y futuras líneas de investigación. Rev Neurol. 2008;46:365–72.

35. Carlson C, Mann M. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, predominantly inattentive subtype. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2000 Jul;9(3):499–510.

36. Carroll JB. Psychometrics, intelligence, and public perception. Intelligence. 1997;24(1):25–52.

37. Caspersen ID, Petersen A, Vangkilde S, Plessen KJ, Habekost T. Perceptual and response-dependent profiles of attention in children with ADHD. Neuropsychology. 2017;31(4):349–60.

38. Castellanos FX, Tannock R. Neuroscience of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the search for endophenotypes. Nat Rev Neurosci [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2025 Mar 7];3:617–28. doi:10.1038/nrn896

39. Castroviejo IP. Síndrome de déficit de atención-hiperactividad. 4th ed. Madrid, España: Díaz de Santos; 2009.

40. Chang Z, D’Onofrio B, Quinn P, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H. Medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk for depression: A Nationwide Longitudinal Cohort Study. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:916–22.

41. Cidoncha Delgado AI. Niños con Déficit de Atención por Hiperactividad TDAH: Una realidad social en el aula. Autodidacta. 2010;31–6.

42. Clemow DB, Bushe C, Mancini M, Ossipov MH, Upadhyaya H. A review of the efficacy of atomoxetine in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adult patients with common comorbidities. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:357–71. doi:10.2147/NDT.S115707.

43. Cochran SD, Drescher J, Kismödi E, Giami A, García-Moreno C, Atalla E, et al. Proposed declassification of disease categories related to sexual orientation in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11). Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(9):672–9. doi:10.2471/BLT.14.135541

44. Cohen RJ, Swerdlik ME. Pruebas y evaluación psicológicas: introducción a las pruebas y a la medición. 6th ed. Izquierdo M, translator. México: Pearson Educación; 2006.

45. Castañeda S, Pontón Becerril GE, Padilla Sierra S, Olivares Bari M, Pérez de Lara Choy MI, translators. México D.F.: McGraw-Hill/Interamericana.

46. Colom R, Flores-Mendoza C. Inteligencia y Memoria de Trabajo: La Relación Entre Factor G, Complejidad Cognitiva y Capacidad de Procesamiento. Psicol Teor Pesq. 2001;17(1):37–47.

47. Condemarín M, Gorostegui ME, Milicic N. Déficit atencional, estrategias para el diagnóstico y la intervención psicoeducativa. 4th ed. Santiago, Chile: Ariel, Planeta Chilena; 2005.

48. Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Psicólogos de España. Evaluación de Test WISC-IV [Internet]. Madrid; 2005 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.cop.es/uploads/PDF/WISC-IV.pdf

49. Cook NE, Braaten EB, Surman CB. Clinical and functional correlates of processing speed in pediatric Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Neuropsychol. 2018;24(5):598–616. doi:10.1080/09297049.2017.1307952

50. Coolican H. Métodos de investigación y estadística en psicología. 2nd ed. García Mulusa M, translator. México: El Manual Moderno; 1997.

51. Cornejo E, Fajardo B, López V, Soto J, Ceja H. Prevalencia de déficit de atención e hiperactividad en escolares de la zona noreste de Jalisco, México. Rev Méd MD. 2015;6(3):190–5.

52. Cosculluela A, Andrés A, Tous JM. Inteligencia y velocidad o eficiencia del proceso de información. Anu Psicol. 1992;52:67–77.

53. Crichton A. An Inquiry Into the Nature and Origin of Mental Derangement: Comprehending a Concise System of the Physiology and Pathology of the Human Mind. Vol. I. Cadell Jr, Davies W, editors. London; 1798.

54. Crowe SF. Does the Letter Number Sequencing Task Measure Anything More Than Digit Span? Assess. 2000;7(2):113–7.

55. Cruz L, Ramos A, Gutiérrez M, Gutiérrez D, Márquez A, Ramírez D, et al. Prevalencia del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad en escolares de tres poblaciones del estado de Jalisco. Rev Mex Neurocienc. 2010;11(1):15–9.

56. Daley D, Birchwood J. ADHD and academic performance: why does ADHD impact on academic performance and what can be done to support ADHD children in the classroom? Child Care Health Dev. 2009;36(4):455–64.

57. Darwin C. El Origen de las especies por medio de la selección natural. Madrid; 1921.

58. De la Osa Langreo A, Mulas F, Mattos L, Gandía Benetó R. Trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad: a favor del origen orgánico. Rev Neurol. 2007;44(3):47–9.

59. De la Peña F, Palacio J, Barragán E. Declaración de Cartagena para el Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad (TDAH): rompiendo el estigma. Rev Cienc Salud. 2010;8(1):93–8.

60. Duñó Ambrós L. TDAH infantil y metilfenidato: predictores clínicos de respuesta al tratamiento [doctoral thesis]. Barcelona, España: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Psiquiatría y Medicina Legal; 2015 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/142657

61. Etchepareborda M, Abad-Mas L. Memoria de trabajo en los procesos básicos del aprendizaje. Rev Neurol. 2005;40(Suppl 1):S79–83.

62. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Consensus Statement on ADHD. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2002;5(2):96–8. doi:10.1007/s007870200

63. Eysenck HJ, Arnold W, Meili R. Encyclopedia of psychology. Unabridged ed. New York: Continuum; 1982.

64. Fass PS. The IQ: A Cultural and Historical Framework. Am J Educ. 1980;88(4):431–58.

65. Fenollar J, Navarro I, González C, García J. Detección de perfiles cognitivos mediante WISC-IV en niños diagnosticados de TDAH: ¿Existen diferencias entre subtipos? Rev Psicodidáct. 2015;20(1):157–76.

66. Fernández L. La perversión de la psicología de la inteligencia: respuesta a Colom. Rev Galego-Port Psicol Educ. 2007;14(1):21–36.

67. Fernández-Jaén A, Fernández-Mayoralas D, Calleja-Pérez B, Muñoz-Jareño N, López-Arribas S. Endofenotipos genómicos del trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad. Rev Neurol. 2012;54(1):81–7.

68. Fernández-Mayoralas DM, Fernández-Perrone A, Fernández-Jaén A. Trastornos específicos del aprendizaje y trastorno hiperactividad. Adolescere. 2013;69–75.

69. Flanagan DP, Kaufman AS. Claves para la evaluación con WISC-IV. México D.F.: Manual Moderno; 2012.

70. Flavell JH. Cognitive development. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1985.

71. Franke B, Faraone SV, Asherson P, Buitelaar J, Bau CH, Ramos-Quiroga JA. The genetics of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, a review. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;10:960–87.

72. Fuenmayor G, Villasmil Y. La percepción, la atención y la memoria como procesos cognitivos utilizados para la comprensión textual. Rev Artes Humanid UNICA. 2008;9(22):187–202.

73. García González E. Piaget: la formación de la inteligencia. 2nd ed. México: Trillas; 1991.

74. García Sevilla J. Psicología de la atención. Madrid, España: Síntesis; 1997.

75. García-Losa E. Retrospectiva y reflexiones sobre el Síndrome de Disfunción Cerebral Mínima. Psiquis Rev Psiquiatr Psicol Méd Psicosom. 1997;53–8.

76. Gardner H. Estructuras de la mente. La teoría de las inteligencias múltiples. México: FCE; 2001.

77. Gaxiola Gaxiola KG. Disturbance of the emotion and motivation in ADHD: a dopaminergic dysfunction. Graf Discipl UCPR. 2015;(28):39–50.

78. Gerlach M, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Rohde LA, Romanos M. What are the benefits of methylphenidate as a treatment for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? ADHD Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017;1–3. doi:10.1007/s12402-017-0220-2

79. Gómez AI. Procesos psicológicos básicos. Tlalnepantla, Estado de México: RED Tercer Milenio; 2012.

80. Gómez R, Vance A, Watson SD. Structure of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fourth Edition in a group of children with ADHD. Front Psychol. 2016 May 30;7(737):1–11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00737

81. Gómez-Pezuela Gamboa G. Desarrollo psicológico y aprendizaje. 1st ed. México: Trillas; 2007.

82. González Garrido AA, Ramos Loyo J. La atención y sus alteraciones: del cerebro a la conducta. Orta EM, editor. Distrito Federal, México: El Manual Moderno; 2006.

83. Gorga M. Trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad y el mejoramiento cognitivo: ¿Cuál es la responsabilidad del médico? Rev Bioética. 2013;21(2):241–50.

84. Gregory RJ. Pruebas psicológicas: historia, principios y aplicaciones. 6th ed. Vega Pérez M, editor. Ortíz Salinas ME, Pineda Ayala LE, translators. México: Pearson Educación; 2012.

85. Hancock MD. The Misdiagnosing of Children of ADHD. Integr Stud. 2017;112.

86. Herrera-Narváez G. Reflexiones sobre el Déficit Atencional con Hiperactividad (TDAH) y sus implicancias educativas. Horiz Educ. 2005;10(1):51–6.

87. Howell R, Hewards W, Swassing H. Los alumnos superdotados. In: Herward WL, editor. Niños Excepcionales una introducción a la educación especial. 5th ed. Madrid: Prentice Hall; 1998. p. 433–81.

88. Jara Segura AB. El TDAH, Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad, en las clasificaciones diagnósticas actuales (CIE-10, DSM-IV–R y CFTMEA–R 2000). Norte Salud Ment. 2009;(35):30–40.

89. Jensen AR. Clocking the mind. New York: Elsevier; 2006.

90. Jepsen JR, Fagerlund B, Mortensen EL. Do attention deficits influence IQ assessment in children and adolescents with ADHD? J Atten Disord [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2025 Mar 7];12(6):551–62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054708322996

91. Jiménez G. Prueba: Escala Wechsler de inteligencia para el nivel escolar (WISC-IV). Av Med. 2007;5:169–71.

92. Joffre-Velázquez V, García-Maldonado G, Joffre-Mora L. Trastorno por déficit de la atención e hiperactividad de la infancia a la vida adulta. Med Fam. 2007;9(4):176–81.

93. Juan-Espinosa M. La geografía de la inteligencia humana. Madrid: Pirámide; 1997.

94. Junqué C, Jódar M. Velocidad de procesamiento cognitivo en el envejecimiento. An Psicol. 1990;6(2):199–207.

95. Kail R. Speed of information processing: developmental change and links to intelligence. J Sch Psychol. 2000;38(1):51–61.

96. Ohlmeier MD, Peters K, Wildt BT, Zedler M, Ziegenbein M, Wiese B, et al. Comorbilidad de la dependencia a alcohol y drogas y el trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH). RET Rev Toxicol. 2009;(58):12–8.

97. Oliveira D, Sousa P, Borges dos Reis C, Virtuoso S, Tonin F, Sanches A. PMH3 - Meta-análisis de eficacia de la atomoxetina en adultos con trastorno de déficit de atención con hiperactividad. Value Health. 2017;20(9):A884. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.2632

98. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Décima revisión de la Clasificación Internacional de los Trastornos Mentales y del Comportamiento CIE-10. Descripciones clínicas y pautas para el diagnóstico. Meditor; 1992.

99. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Guía de bolsillo de la Clasificación de los Trastornos Mentales y del Comportamiento CIE-10. CDI Criterios diagnósticos de investigación. Médica Panamericana; 2000.

100. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Clasificación estadística internacional de enfermedades y problemas relacionados con la salud—10a revisión (CIE-10). 2003 ed. Vol. 1. Washington: OPS; 1996.

101. Osuna Á. Evaluación neuropsicológica en educación. ReiDoCrea. 2017;6(2):24–30.

102. Otero MR. Psicología cognitiva, representaciones mentales e investigación en enseñanza de las ciencias. Investig Ensino Ciênc. 1999;4(2):93–119.

103. Pagano RR. Estadística para las ciencias del comportamiento. 9th ed. Baranda Torres M, translator. México D.F.: Cengage Learning; 2011.

104. Palacio JD, De la Peña F, Palacios-Cruz L, Ortiz-León S. Algoritmo latinoamericano de tratamiento multimodal del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH) a través de la vida. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2009;38(1):35S–65S.

105. Palacios–Cruz L, De la Peña F, Valderrama A, Patiño R, Calle Portugal SP, Ulloa RE. Conocimientos, creencias y actitudes en padres mexicanos acerca del trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad (TDAH). Salud Ment. 2011;34(2):149–55.

106. Palme ED, Finger S. An early description of ADHD (Inattentive Subtype): Dr Alexander Crichton and ‘Mental Restlessness’ (1798). Child Psychol Psychiatry Rev. 2001;6(2):66–73.

107. Pascual Lema S. The role of the clinical psychologist and the approach to ADHD. Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;37–53.

108. Pelayo-Terán JM, Trabajo-Vega P, Zapico-Merayo Y. Aspectos históricos y evolución del concepto de trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH): mitos y realidades. Cuad Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;11(1):7–35.

109. Peña del Agua AM. Las teorías de la inteligencia y la superdotación. Aula Abierta. 2004;84:23–38.

110. Pérez Hernández E, Corrochano Ovejero L. Aspectos neurobiológicos y etiopatogenia del TDAH y los trastornos relacionados. In: Ruiz Sánchez de León JM, Fournier del Castillo C, editors. Manual de neuropsicología pediátrica. Madrid, España: ISEP Madrid; 2016. p. 415–42. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3492.6968

111. Pérez Mariño N. Intervención sobre el funcionamiento ejecutivo en un caso de TDAH: implicaciones en conciencia fonológica y lectura. Rev Estud Investig Psicol Educ. 2015;(9):48–52.

112. Piaget J. El nacimiento de la inteligencia en el niño. Barcelona: Crítica; 2003.

113. Polanczyk G, Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8.

114. Presentación Herrero MJ, Siegenthaler Hierro R, Jara Jiménez P, Casas AM. Seguimiento de los efectos de una intervención psicosocial sobre la adaptación académica, emocional y social de niños con TDAH. Psicothema. 2010;22(4):778–83.

115. Pueyo AA. Manual de psicología diferencial. Madrid, España: McGraw-Hill; 1997.

116. Quintero Gutiérrez del Alamo FJ, Rodríguez-Quirós J, Correas J, Pérez-Templado J. Aspectos nutricionales en el trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad. Rev Neurol. 2009;49(6):307–12.

117. Rabito Alcón MF, Correas J. Guías para el tratamiento del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad: una revisión crítica. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2014;42(6):315–24.

118. Raven J, Raven JC, Court JH. Manual for Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. Oxford, England: Oxford Psychologists; 1998.

119. Rebollo M, Montiel S. Atención y funciones ejecutivas. Rev Neurol. 2006;46(Suppl 2):S3–7.

120. Ohlmeier MD, Peters K, Wildt BT, Zedler M, Ziegenbein M, Wiese B, et al. Comorbilidad de la dependencia a alcohol y drogas y el trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH). RET Rev Toxicol. 2009;(58):12–8.

121. Oliveira D, Sousa P, Borges dos Reis C, Virtuoso S, Tonin F, Sanches A. PMH3 - Meta-análisis de eficacia de la atomoxetina en adultos con trastorno de déficit de atención con hiperactividad. Value Health. 2017;20(9):A884. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.2632

122. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Décima revisión de la Clasificación Internacional de los Trastornos Mentales y del Comportamiento CIE-10. Descripciones clínicas y pautas para el diagnóstico. Meditor; 1992.

123. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Guía de bolsillo de la Clasificación de los Trastornos Mentales y del Comportamiento CIE-10. CDI Criterios diagnósticos de investigación. Médica Panamericana; 2000.

124. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Clasificación estadística internacional de enfermedades y problemas relacionados con la salud—10a revisión (CIE-10). 2003 ed. Vol. 1. Washington: OPS; 1996.

125. Osuna Á. Evaluación neuropsicológica en educación. ReiDoCrea. 2017;6(2):24–30.

126. Otero MR. Psicología cognitiva, representaciones mentales e investigación en enseñanza de las ciencias. Investig Ensino Ciênc. 1999;4(2):93–119.

127. Pagano RR. Estadística para las ciencias del comportamiento. 9th ed. Baranda Torres M, translator. México D.F.: Cengage Learning; 2011.

128. Palacio JD, De la Peña F, Palacios-Cruz L, Ortiz-León S. Algoritmo latinoamericano de tratamiento multimodal del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH) a través de la vida. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2009;38(1):35S–65S.

129. Palacios–Cruz L, De la Peña F, Valderrama A, Patiño R, Calle Portugal SP, Ulloa RE. Conocimientos, creencias y actitudes en padres mexicanos acerca del trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad (TDAH). Salud Ment. 2011;34(2):149–55.

130. Palme ED, Finger S. An early description of ADHD (Inattentive Subtype): Dr Alexander Crichton and ‘Mental Restlessness’ (1798). Child Psychol Psychiatry Rev. 2001;6(2):66–73.

131. Pascual Lema S. The role of the clinical psychologist and the approach to ADHD. Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;37–53.

132. Pelayo-Terán JM, Trabajo-Vega P, Zapico-Merayo Y. Aspectos históricos y evolución del concepto de trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH): mitos y realidades. Cuad Psiquiatr Comunitaria. 2012;11(1):7–35.

133. Peña del Agua AM. Las teorías de la inteligencia y la superdotación. Aula Abierta. 2004;84:23–38.

134. Pérez Hernández E, Corrochano Ovejero L. Aspectos neurobiológicos y etiopatogenia del TDAH y los trastornos relacionados. In: Ruiz Sánchez de León JM, Fournier del Castillo C, editors. Manual de neuropsicología pediátrica. Madrid, España: ISEP Madrid; 2016. p. 415–42. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3492.6968

135. Pérez Mariño N. Intervención sobre el funcionamiento ejecutivo en un caso de TDAH: implicaciones en conciencia fonológica y lectura. Rev Estud Investig Psicol Educ. 2015;(9):48–52.

136. Piaget J. El nacimiento de la inteligencia en el niño. Barcelona: Crítica; 2003.

137. Polanczyk G, Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8.

138. Presentación Herrero MJ, Siegenthaler Hierro R, Jara Jiménez P, Casas AM. Seguimiento de los efectos de una intervención psicosocial sobre la adaptación académica, emocional y social de niños con TDAH. Psicothema. 2010;22(4):778–83.

139. Pueyo AA. Manual de psicología diferencial. Madrid, España: McGraw-Hill; 1997.

140. Quintero Gutiérrez del Alamo FJ, Rodríguez-Quirós J, Correas J, Pérez-Templado J. Aspectos nutricionales en el trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad. Rev Neurol. 2009;49(6):307–12.

141. Rabito Alcón MF, Correas J. Guías para el tratamiento del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad: una revisión crítica. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2014;42(6):315–24.

142. Raven J, Raven JC, Court JH. Manual for Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. Oxford, England: Oxford Psychologists; 1998.

143. Rebollo M, Montiel S. Atención y funciones ejecutivas. Rev Neurol. 2006;46(Suppl 2):S3–7.

144. Richardson J, Engle R, Hasher L, Logie R, Stoltzfus E, Zacks R. Working memory and human cognition. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996.

145. Rickel AU, Brown RT. Trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad. 1st ed. México D.F.: Manual Moderno; 2007.

146. Ríos Lago M, Lubrini G, Periáñez Morales JA, Viejo Sobera R, Tirapu Ustárroz J. Velocidad de procesamiento de la información. In: Tirapu Ustárroz J, editor. Neuropsicología de la corteza prefrontal y las funciones ejecutivas. Madrid: Viguera; 2012. p. 241–70.

147. Rodríguez-Salinas E, Navas M, González P, Fominaya S, Duelo M. La escuela y el trastorno por déficit de atención con/sin hiperactividad (TDAH). Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2006;75–98.

148. Ruiz JM, Guinea SF, González-Marqués J. Aspectos teóricos actuales de la memoria a largo plazo: de las dicotomías a los continuos. An Psicol. 2006 Dec;290–7.

149. Sanfeliu I. Disfunción cerebral mínima. Clín Anal Grup. 2010;104–5(32):279–83.

150. Santiago G, Tornay F, Gómez E, Elosúa M. Procesos psicológicos básicos. Madrid: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

151. Santrock J. Psicología de la educación. México: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

152. Santrock J. Psicología de la educación. México: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

153. Sastre-Riba S. Condiciones tempranas del desarrollo y el aprendizaje: el papel de las funciones ejecutivas. Rev Neurol. 2006;S143–51.

154. Sattler JM. Assessment of children: cognitive applications. 4th ed. La Mesa, CA: Jerome Sattler Publisher, Inc.; 2001.

155. Sattler JM. Evaluación infantil: fundamentos cognitivos. 5th ed. Viveros Fuentes S, editor. Padilla Sierra G, Olivares Bari SM, translators. México D.F.: El Manual Moderno; 2010.

156. Schoning F. Problemas de aprendizaje. Carrillo Farga M, translator. México: Trillas; 1990.

157. Secretaría de Salud. Código de Conducta de la Secretaría de Salud [Internet]. México; 2016 Jun 30 [cited 2025 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.comeri.salud.gob.mx/descargas/Vigente/2016/Codigo_Conducta.pdf

158. Sellés Nohales P. Estado actual de la evaluación de los predictores y de las habilidades relacionadas con el desarrollo inicial de la lectura. Aula Abierta. 2006;88:53–72.

159. Servera M, Llabres J. Prueba ganadora de la VIII Edición del Premio TEA para la realización de trabajos de investigación y desarrollo sobre tests y otros instrumentos de evaluación: Resumen Manual. CSAT Tarea de Atención Sostenida en la Infancia. Madrid: TEA ediciones; 2004.