doi: 10.56294/mw2024570

REVIEW

Domestic violence: how violence against women manifests itself in media discourse

Violencia doméstica: cómo se manifiesta la violencia contra la mujer en el discurso mediático

Gabriela Tavares Soares1 ![]() *, Carolina de Araújo

Rezende Gonçalves1

*, Carolina de Araújo

Rezende Gonçalves1 ![]() *, Elaine Aparecida

Policarpo1

*, Elaine Aparecida

Policarpo1 ![]() *, Bruno de Souza Prado1

*, Bruno de Souza Prado1 ![]() *, Gleice Kelly de Pádula Batista Machado1

*, Gleice Kelly de Pádula Batista Machado1 ![]() *,

Daniela Miotto Araújo1

*,

Daniela Miotto Araújo1 ![]() *, Maiara Patrícia

Vieira Nicolau Ribeiro Sanchez1

*, Maiara Patrícia

Vieira Nicolau Ribeiro Sanchez1 ![]() *, Manuelli Aparecida Mota Rodrigues1

*, Manuelli Aparecida Mota Rodrigues1 ![]() *, William Alves dos Santos2

*, William Alves dos Santos2 ![]() *

*

1Faculdade Anhanguera de Jacareí, Psicologia. Jacareí, Brasil.

2Faculdade Anhanguera de Jacareí, Enfermagem. Jacareí, Brasil.

Cite as: Tavares Soares G, de Araújo Rezende Gonçalves C, Aparecida Policarpo E, de Souza Prado B, de Pádula Batista Machado GK, Daniela Miotto Araújo DMA, et al. Domestic violence: how violence against women manifests itself in media discourse. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2024; 3:570. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw2024570

Submitted: 30-11-2023 Revised: 12-02-2024 Accepted: 02-05-2024 Published: 03-05-2024

Editor: Dr.

José Alejandro Rodríguez-Pérez ![]()

Corresponding author: Gabriela Tavares Soares *

ABSTRACT

Introduction: domestic violence against women is a social problem related to male power and dominance, representing a violation of human rights and a serious public health problem. The media can both reinforce stereotypes and raise awareness of the issue. To identify domestic violence against women through discourse analysis.

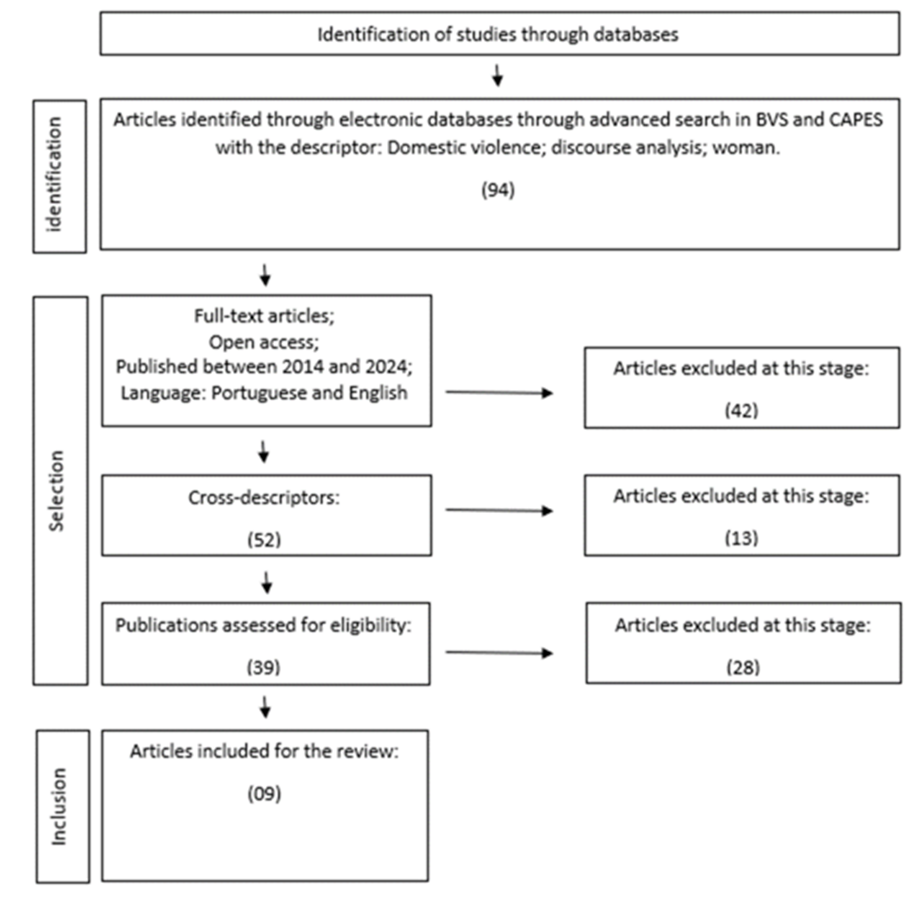

Method: this study used an integrative review to investigate domestic violence against women in media discourses, with data from October 2024 from the VHL and CAPES databases. Full-length articles in Portuguese and English from the last 10 years were included. The research followed the stages of problem identification, literature selection and inclusion, guided by the PCC strategy and the PRISMA® Flowchart for analysis.

Results: violence against women is seen as the result of a machista construction that normalises control and aggression, sustained by discourses that reinforce stereotypes of female submission. Campaigns seek to recognise women as subjects of rights, but despite protective laws, social resistance continues to provoke high rates of violence against women.

Conclusion: the media often naturalises domestic violence and blames the victims, reinforcing patriarchal structures and gender stereotypes. To combat this reality, it is necessary to value female protagonism, avoid blame and create safe spaces for women to share their experiences, promoting a fairer and more equal society.

Keywords: Gender; Domestic Violence; Discourse Analysis and the Media.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la violencia doméstica contra las mujeres es un problema social relacionado con el poder y la dominación masculinos, que representa una violación de los derechos humanos y un grave problema de salud pública. Los medios de comunicación pueden tanto reforzar los estereotipos como sensibilizar sobre el tema. Identificar la violencia doméstica contra las mujeres mediante el análisis del discurso.

Método: este estudio utilizó una revisión integradora para investigar la violencia doméstica contra las mujeres en los discursos de los medios de comunicación, con datos de octubre de 2024 de las bases de datos BVS y CAPES. Se incluyeron artículos completos en portugués e inglés de los últimos 10 años. La investigación siguió las etapas de identificación del problema, selección de la literatura e inclusión, guiada por la estrategia PCC y el Flujograma PRISMA® para el análisis.

Resultados: la violencia contra las mujeres es vista como el resultado de una construcción machista que normaliza el control y la agresión, sustentada en discursos que refuerzan los estereotipos de sumisión femenina. Las campañas buscan reconocer a las mujeres como sujetos de derechos, pero a pesar de las leyes protectoras, la resistencia social sigue provocando altos índices de violencia contra las mujeres.

Conclusión: los medios de comunicación a menudo naturalizan la violencia doméstica y culpan a las víctimas, reforzando las estructuras patriarcales y los estereotipos de género. Para combatir esta realidad, es necesario valorar el protagonismo femenino, evitar la culpabilización y crear espacios seguros para que las mujeres compartan sus experiencias, promoviendo una sociedad más justa e igualitaria.

Palabras clave: Género; Violencia Doméstica; Análisis del Discurso y Medios de Comunicación.

INTRODUCTION

Domestic violence is a social phenomenon built up throughout history and the result of a power relationship, where there is a dominant and a dominated figure. Within this context, violence against women, who are dominated by the physical force of their aggressors, is a cruel form of human rights violation. This phenomenon has serious implications for the physical and psychological health of the victims, hurting their right to life and liberty.(1)

Research shows that this act is usually practiced by intimate partners, parents, siblings or friends, taking place in the home itself. According to the National Policy for Combating Violence against Women, which aims to establish guidelines for preventing and combating this type of violence (a document that is in line with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1984); the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women (Convention of Belém do Pará, 1994); the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, 1981) and the International Convention against Transnational Organized Crime for the Prevention, Suppression and Punishment of Trafficking in Persons (Palermo Convention, 2000), this type of crime happens to women of all races and ethnicities all over the world, with a prevalence of black women.(2)

In Brazil, according to the IBGE’s National Health Survey (PNS), in 2019, 6 % of women aged 18 or over had suffered some kind of violence, whether perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner. The study also found that 9,2 % of women were aged between 18 and 29 and that 6,3 % of victims were brown or black. The same study found that 72,8 % of cases of violence occurred in the victims’ homes and in 85 % of cases the aggressor was their intimate partner or ex-partner, relatives, friends or neighbors.(3)

Violence against women in the domestic environment is the result of historical and social constructions that have reinforced the domination of male power over the female body. It is a public health problem, as it affects everyone involved in the family context, causing suffering, mistreatment and illness in a silent and hidden way. Throughout history, there have been attempts to hide or erase the scars left by this violence, but in this context, women have always been considered subjects of rights, at least in the theory of the law. In practice, however, this does not happen in the same way.(4) The 1988 Constitution represented a milestone for the rights of all Brazilian women by establishing equal rights and obligations for men and women.(5) Other important milestones were the Maria da Penha Law - Law 11.340/2006 - which allows police authorities to remove aggressors from victims and the prohibition of the thesis of legitimate defense of honor to mitigate crimes of femicide, as well as the creation of women’s police stations, shelters and other public policies.(2)

As it is a phenomenon that dates back centuries and is still very evident today even with numerous sanctions, it is important to understand how domestic violence is seen in discourses over time and, to do this, we will use articles with the technique of discourse analysis. This technique consists of a field of research, made up of multiple approaches, most of which are qualitative in nature, which deal with the relationship between the use of language and the social world(5) - it is the analysis of language in operation, of the meanings and significances attributed to it in certain situations, since through the word, it is possible to perceive the power relations, ideologies and cultures of a given society in the time and context in which it was used.(6)

Discourse analysis allows the analysis of the ideological effect that can contribute to maintaining or modifying power relations between men and women and between social groups. Discourse is a linguistic construction constituted and influenced by the political, historical and cultural context, where ideologies are manifested through words, phrases and expressions. This form of analysis seeks to understand what is implicit in discourses.(7) Understanding the meanings and significance of women’s speeches about the suffering they go through and how they are portrayed by the media is the challenge of this work, which could give a voice to so many women and families who are invisible in the face of moral, property, physical, psychological and sexual violence.

Objective

To identify domestic violence against women through discourse analysis.

METHOD

This is a descriptive integrative literature review. Data was collected in October 2024 and stored using the “Rayyan®” application on a personal Lenovo notebook for later analysis. The search took place in the following electronic databases: Virtual Health Library (VHL) and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES). The subject descriptors (DeCS) used were: Domestic Violence, Discourse Analysis and Women. The Boolean operator “AND” was used to cross-reference the descriptors: Domestic Violence ‘AND’ Discourse Analysis “AND” Women.

The search was carried out using the inclusion criteria of articles in Portuguese and English, published in the last 10 years with the full text available. Articles whose text was incomplete, which were not original, dissertations, theses, more than ten years old and which did not correspond to the databases described above were excluded. The research was carried out in three stages: problem identification, literature search and selection and inclusion, with the guiding question being: “What is the evidence in scientific publications on domestic violence against women using discourse analysis over the last 10 years?”. To delimit the project, we used the PCC strategy, which consists of an exploratory approach to the topic; where P (Population): Woman; C (concept): Discourse analysis and C (context): domestic violence, as described in Chart 1.

The articles were screened through levels, where the first level was to exclude articles based on the title and abstract and the second level was to carry out full reviews of articles to check that they met the inclusion criteria. A reviewer was also used in the selection to increase the fidelity of the articles selected, to the point of avoiding disagreements.

The risk of bias tools such as the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool or the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale were not used to check the quality of the article, as this is an integrative review and not a systematic literature review. However, they were reviewed by another reviewer who took part in the work so that any disagreements could be resolved.

The data was extracted and collected using the free “Rayyan®” platform for screening and categorizing articles in systematic reviews, but it can also be useful in integrative reviews.

Analysis and data collection were carried out using the PRISMA® flowchart, following the recommendations of the protocol (figure 1).

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest that could influence the results of this study.

Figure 1. Flowchart of bibliographic information obtained at different stages of the systematics review

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Initially, 94 articles were identified in the advanced search using the descriptors domestic violence, discourse analysis and women. After filtering for articles with full text, open access, published between 2014 and 2024 and in Portuguese and English, 42 articles were excluded. Of the 52 articles that remained, 13 articles with cross-descriptors were excluded. This left 39 articles in which the search was refined to the context of domestic violence against women using discourse analysis, checking the title and abstract of the articles, where 30 articles were excluded. These left 09 articles included in the review, as shown in the figure below:

The search strategy was based on the definitions in the DeCS mentioned above, combined with Boolean operators (AND) according to the objective of the review.

|

Table 1. Descriptors used to search data sources |

|

|

PCC |

DeCS |

|

Population |

Woman |

|

|

AND |

|

Concept |

Discourse analysis |

|

|

AND |

|

Context |

Domestic violence |

A table was created with the main findings used in this review. The choice of a tabular format allows the information to be organized and presented in a clear and objective manner, facilitating comparison between the studies.

|

Table 2. Bibliographic findings used to construct this article |

|||

|

Main Author / Year |

Type of design |

Original Title |

Summary |

|

1- GRANTHAM, M. R./ 2009(8) |

Case study and documentary research. |

A path doesn’t hurt: a study of gender violence. |

It focuses on the need for awareness and cultural change. The article argues that transforming these everyday discourses is essential to combating gender violence and deconstructing the norms that perpetuate inequality. |

|

2 - LERMEN, H.S. / 2018(9) |

Documentary study and survey study. |

Analysis of news comments on violence against women. |

She says that despite laws and punishments, such as the Maria da Penha Law and the recognition of femicide, this is not enough to end violence against women. A deeper cultural change is needed, one that promotes gender equality and rejects violence altogether, as well as combating prejudices that blame the victims. |

|

3 - PINTO, M. /2020(10) |

Descriptive, exploratory and documentary study. |

Dialogic analysis of Maria da vila Matilde: a song against gender violence. |

The song “Maria da Vila Matilde” by Elza Soares is an example of resistance and empowerment against gender violence. The song encourages women to denounce abuse and seek their independence through speeches that help them face domestic violence and gain autonomy. |

|

4 - Fornari, L. F. / 2021(11) |

Descriptive and documentary study. |

Violence against women at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic: the discourse of digital media. |

Digital media helps to denounce violence against women, especially during the pandemic, when isolation made the situation worse. The article advocates more public policies to protect women and improve their economic conditions. It also suggests that health professionals, such as nurses, should offer more comprehensive and effective care to women victims of violence. |

|

5 – Lima - Santos, A. V. S. / 2022(12) |

Theoretical, documentary and exploratory studies. |

Incels and Online Misogyny in Times of Digital Culture. |

Misogynistic discourses on the internet are becoming more sophisticated and are adapting quickly to social and technological changes. These discourses strengthen gender violence and male domination, both online and offline, and it is important to understand and combat these phenomena in the digital world. |

|

6 - MIRANDA, E. L./ 2022(13) |

Descriptive and documentary. |

Violence against women: representations in the media discourse |

The media has a crucial role to play in addressing violence against women. It needs to deal with the issue in a contextualized and critical way, avoiding reinforcing prejudices. The study highlights that the media can either contribute to maintaining violence or be an agent of social change, depending on how it approaches and transmits its information. |

|

7 - OLIVEIRA, F. S./ 2022(14) |

Descriptive and exploratory. |

A cry that adds up: a semiolinguistic analysis of the song Maria da Vila Matilde. |

The text analyzes songs, showing how their lyrics use discursive strategies and how these impact the public. It focuses on the song “Maria da Vila Matilde” by Elza Soares, which denounces violence against women and at the same time empowers them. The lyrics are seen as a space of confrontation between ideology and social practice, due to their popularity and impact. Analyzing the language of the song also helps to understand the social context in which it was created. |

|

8- DE AVILA, S. S. / 2022(15) |

Case study and documentary study. |

Trash, slut, hooker, whore and crazy: effects of meaning and discursive determinations in reports by women victims of domestic violence. |

It shows that using offensive terms against women is a form of symbolic violence, which maintains gender inequality and justifies physical and psychological violence. It highlights the need to change the way we speak to respect and value women. |

|

9 - SOUZA, N.T. de S. / 2023(16) |

Exploratory - descriptive. |

“He doesn’t hit you, but ... “ subtle signs of abusive relationships, violence and femicide: a critical discourse analysis. |

It reflects deeply on how power structures and gender inequality manifest themselves subtly and silently in abusive relationships and the need for more effective awareness-raising and prevention actions. |

Violence against women is a phenomenon that has intensified in every way and is being discussed by various sectors of society.(17) This is due to the fact that domestic violence involves a social construction, the result of a sexist and patriarchal society that has symbolic apparatuses - such as the education system, the media, religion and others - that contribute to the idea of male domination. (18)

Male chauvinism is a belief system that promotes male superiority and tries to justify gender inequality and the subordination of women through cultural and social norms that are rooted in society and act through discursive memory. Discursive memory is the reuse of previously pre-constructed discourses to support ideologies in discourses that have already been said and that are intertwined in the memory of an entire society, which happens implicitly. The story told interferes with the subject and their language, forming an ideology - since language is not only a resource for communication, but also a mechanism for imposing ideology.(19)

In all the awareness-raising campaigns about violence against women cited in the articles found, it is necessary to emphasize that women are included as “human persons” and to protect their rights, like those of any other person. This is due to the fact that, due to discursive memory and structural machismo, our society was not built on a vision of equality between genders, classes, ethnicities and other differences, making it necessary to create laws in order to alleviate the imbalance that exists in our own ideology.

The sense of playfulness in relation to violence can also be seen in song lyrics that are openly sung - and danced to - by children who will become the men and women who will carry on this memory. In these songs, violence is disguised and softened to give the connotation of affection or sexual practice, referring to the idea of pleasure, such as lines about women wanting to be beaten, where the responsibility (previously the aggressor’s) becomes the battered woman’s and there is no guilt on the part of the batterer, promoting violence as something normal.(8)

The use of pejorative terms to describe women which, in patriarchal contexts, are widely used to describe behaviors considered inappropriate or that defy social norms not only degrade, but also serve as tools of control, discouraging certain behaviors and punishing the transgression of gender expectations. In other words, these expressions function as mechanisms of coercion, setting boundaries for what is acceptable in female conduct. This type of pejorative labeling has profound emotional consequences, often leading people to question their own worth, and is intensified by the repetition of these insults in various contexts.(15)

Female conduct involves historical social expectations and norms that shape specific behaviors for women. Traditionally, female conduct has been associated with submission, care and purity, reinforcing roles as wife, mother and caretaker of the home. These norms, although challenged and expanded over time, still influence the way many women are encouraged to behave, whether in the family, professional or social environment. From this perspective, women lose their identity - we understand the term identity as dynamic and dialogical instances of the development of the I, in other words, in the sense of identifications: identity becomes a form of self-knowledge, acceptance and empowerment, formed and transformed continuously in relation to the ways in which we are represented or interpreted in the cultural systems that surround us - defined historically, not biologically. The subject assumes different identities at different times, which are not unified around a coherent “I”. Within us there are contradictory identities, pushing in different directions, in such a way that our identifications are continually being displaced.”(20)

Many victims of abusive relationships don’t even recognize that they are being assaulted, going so far as to justify their partners’ aggressive behaviour and carrying the blame that doesn’t belong to them. The environment created by violent relationships is one of fear, anguish, sadness and pain: everything you wouldn’t expect from an affective relationship.(21)

Even after the Maria da Penha Law was passed in 2006, the number of registered cases of domestic violence and femicide has not decreased and the country continues to be one of the countries with the highest number of registered cases. One of the tools guaranteed by law to protect the victim is protective measures. According to data from the CNJ (National Council of Justice), more than 391,000 requests for protective measures were registered in Brazil in 2021. In 2022, from January to August, almost 191 000 requests were issued. In 2021, the Maria da Penha Law was reinforced with the sanction of Law No. 14.188/2021, which creates the Red Light Against Domestic and Family Violence program and includes the crime of psychological violence against women in the Penal Code (Decree-Law No. 2.848, of 1940). This law defines that the crime of psychological violence against women can occur through threats, embarrassment, humiliation, manipulation, isolation, blackmail, ridicule, limiting the right to come and go or any other method. The penalty is imprisonment for six months to two years and a fine, if the conduct does not constitute a more serious crime. With the measure, judges, delegates and police officers can immediately remove the aggressor from the place where they live, with the criterion of the existence of a risk to the woman’s psychological integrity as one of the reasons. Until this law was passed, this could only be done in the event of a risk to the victim’s physical integrity. Data from the latest survey carried out by the Brazilian Public Security Forum revealed that in 2021, on average one woman was a victim of femicide in the country every seven hours.(22)

With the start of social isolation measures during the pandemic, there was an increase in cases of domestic violence, as many women were confined at home with their aggressors, facing greater difficulty in accessing support and protection services. This situation highlighted structural inequalities related to the specific vulnerabilities of women in a context of health and social crisis. Many digital narratives pointed to the increase in stress and family tension caused by confinement, which contributed to the worsening of domestic violence. There was also emphasis on the insufficiency of support services and the difficulty in accessing these resources during the period of isolation. Discrepancies were also observed in official records, with a lower number of reports through channels such as the 180 Call Center, which offers 24-hour support. This discrepancy may be associated with the difficulty victims have in accessing reporting channels due to movement restrictions and fear of reprisals.(9)

Victims feel guilty due to comments on social media where they minimize the aggression committed by men. The comments taken from the internet were analyzed and demonstrate a tendency to blame and delegitimize victims, reflecting social resistance to the changes proposed by the legislation - violence against women is normalized and trivialized, especially in the domestic and marital context.(7) It was possible to identify that the Internet facilitates the infiltration of violent acts due to anonymity - behaviors that would normally not go unnoticed in the offline world - can go unnoticed in the online world. The digital world has made it possible to reveal and amplify violent, discriminatory, and criminal behaviors, as well as perpetuating the conditions of social inequality produced by capitalism.(23)

Despite being a platform that offers space for everyone to express themselves, the internet is still predominantly dominated by male voices. We call hegemonic masculinity the concept introduced by sociologist Raewyn Connell, which describes a model of masculinity that is dominant in a given culture and that values characteristics such as strength, independence, rationality, authority, competitiveness, and emotional control; promoting the idea that these attributes are the standards of knowledge and practices that men must follow and contribute to the perpetuation of male dominance over women.(24)

Aggressive content popularized through memes - a term that means a unit of culture, behavior or idea passed from person to person - facilitates the dissemination of sexist phrases with an ironic and sarcastic connotation, giving a playful tone to veiled violence.(25) It is possible to identify derogatory and subjective verbal language on the networks, a distorted and dubious understanding, which attempts to invalidate women’s rights, where a structure is maintained that men are placed in positions of power, having advantages over women and even men who do not fit the standard.

In recent years, the American website “4chan” has gained prominence for proliferating and gaining followers of its ideology and establishing strategic alliances, being the main producer of content from the “new right” or “all-right”, which has as a distinctive characteristic the use of pornographic content with a highly humiliating and hostile content towards women. We can find posts and statements online that the image of the Chans - as the site’s participants are called - is associated with young, white, heterosexual men with a high level of cultural capital, that is, men who in a certain way occupy privileged spaces.(10)

Domestic violence must be viewed from a perspective that goes beyond physical violence, emphasizing that abusive relationships can include emotional control, manipulation, excessive jealousy and isolation of the victim. This type of abuse is often difficult to identify because it leaves no visible marks, but it causes profound psychological impact. These subtle signs of abuse, which can even be confused with a feeling of care, often precede more serious episodes of violence, including femicide. Recognizing these signs is essential for preventing more serious cases of violence, highlighting the importance of a cultural change that helps identify and combat these abusive practices from their earliest signs.(14)

Elza Soares’ songs – as well as other types of current media, such as films and series – address issues such as domestic violence and racism, helping us understand how domestic violence occurs. We know that music is an artistic construction used as an instrument to denounce a social problem. In her songs, Elza sought to make the idea of female empowerment explicit through the strength of the words used. In one of the songs that the singer performed, entitled “Maria da Vila Matilde”, there is an inversion of power, where it is the woman who has an active voice, who sends the man away, unlike what is seen in Brazilian society. This song represents female resistance in the face of abuse and offers another perspective for women, demonstrating their ability to act on the world and transform their realities. The song denounces the violent, disrespectful and immoral behavior of the partner in different ways, using the listener’s imagination to report the violence and warn the aggressor. Through music, a true cry of resistance is given that connects the individual experience with the collective, proposing a break with submission and making women aware of their rights and of seeing themselves as beings worthy of exercising them.(10,14)

CONCLUSION

This literature review identified domestic violence against women through discourse analysis. During the analysis, it became clear that narratives conveyed in the media often end up blaming victims and reinforcing patriarchal structures, which contributes to naturalizing violence and perpetuating gender stereotypes that silence and devalue women.(8) This naturalization of violence becomes a major challenge for social transformation, as it reinforces cultural norms that maintain inequality and make it difficult to break the cycle of violence.

To change this reality, it is essential that media discourse values female protagonism, abandoning narratives that blame victims and, instead, respecting and recognizing the dignity of women in their life stories. When used critically, the media can be a powerful means of raising awareness, showing the complexity of domestic violence that goes beyond physical aggression, including psychological and symbolic violence, among others.(14) By giving voice to stories of resistance and overcoming, the media can awaken empathy and promote a society more committed to gender equality.

In addition to changing the way violence is represented, it is essential that women find safe spaces to share their experiences without fear of being judged or blamed.(16) Supportive spaces allow women to share their experiences, strengthening themselves through a sense of solidarity and creating a support network that is essential to breaking the cycle of violence. These environments, whether physical or virtual, help victims regain their voice in a safe and stigma-free space.

Finally, transforming media discourse and creating safe spaces for women are essential steps in addressing domestic violence. By committing to inclusive and welcoming narratives, the media and society can contribute to building a culture of justice and equality, where gender-based violence is firmly recognized, rejected and combated, as proposed by the National Policy to Address Violence Against Women.(2)

REFERENCES

1. Jesus RF, Calheiros CA, Ribeiro PM, Silva BA, Silva SA, Freitas PS. VIOLÊNCIA CONTRA MULHERES: ATUAÇÃO DOS ENFERMEIROS EM ESTRATÉGIAS SAÚDE DA FAMÍLIA. Enferm Em Foco [Internet]. 2024 [citado 2 nov 2024];15. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.21675/2357-707x.2024.v15.e-202458

2. Política nacional de enfrentamento à violência contra as mulheres. Secr Espec Políticas Para Mulh [Internet]. 2011 [citado 2 nov 2024]. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/mdh/pt-br/navegue-por-temas/politicas-para-mulheres/arquivo/arquivos-diversos/sev/pacto/documentos/politica-nacional-enfrentamento-a-violencia-versao-final.pdf

3. GovBR [Internet]. IBGE - Educa | Jovens; [citado 2 nov 2024]. Disponível em: https://educa.ibge.gov.br/jovens/materias-especiais/22052-as-mulheres-do-brasil.html

4. Planalto [Internet]. Constituição da República Federativa de 1988; 1988 [citado 2 nov 2024]. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Constituicao/Constituicao.htm

5. Zeri de Oliveira C, Bulhões Campos J, Almeida de Oliveira MA. A ANÁLISE DO DISCURSO. Momento Dialogos Em Educ [Internet]. 23 nov 2022 [citado 3 nov 2024];31(03):41-67. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.14295/momento.v31i03.14053

6. Araújo AL. Discurso, memória e violência de gênero. Rev Anpoll [Internet]. 30 abr 2024 [citado 3 nov 2024];55:e1828. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.18309/ranpoll.v55.1828

7. Assis PB. Orlandi, E. P. Argumentação e Análise do Discurso. Linguas Instrum Linguisticos [Internet]. 15 jul 2024 [citado 3 nov 2024];27:e024003. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.20396/lil.v27i00.8675921

8. Grantham MR. Um tapinha não dói: um estudo da violência de gênero. Rev Conex Let [Internet]. 13 maio 2015 [citado 3 nov 2024];4(4). Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.22456/2594-8962.55585

9. Análise dos comentários de notícias sobre violência contra as mulheres. Estud Psicol [Internet]. Mar 2018 [citado 3 nov 2024];23(1). Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.22491/1678-4669.20180009

10. Sena dos Santos R, Pinto M. ANÁLISE DIALÓGICA DE MARIA DA VILA MATILDE: A CANÇÃO NO EMBATE CONTRA A VIOLÊNCIA DE GÊNERO. PERcursos Linguisticos [Internet]. 31 out 2020 [citado 3 nov 2024];10(25):222-43. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.47456/pl.v10i25.30050

11. Fornari LF, Menegatti MS, Lourenço RG, Santos DL, Oliveira RN, Fonseca RM. VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AT THE BEGINNING OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: THE DISCOURSE OF THE DIGITAL MEDIA. Reme Rev Min Enferm [Internet]. 2021 [citado 3 nov 2024];25. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.5935/1415.2762.20210036

12. Lima-Santos AV, Santos MA. Incels e misoginia on-line em tempos de cultura digital. Estud Pesqui Em Psicol [Internet]. 30 set 2022 [citado 3 nov 2024];22(3):1081-102. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.12957/epp.2022.69802

13. Miranda EL, Loreto MD, Souza GB. Violência contra a mulher: representações do discurso midiático. Argumentum [Internet]. 29 dez 2022 [citado 3 nov 2024];14(3):137-50. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.47456/argumentum.v14i3.35347

14. Oliveira FD, Oliveira RJ. Um grito que soma. Letronica [Internet]. 31 dez 2021 [citado 3 nov 2024];14(4):e39736. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.15448/1984-4301.2021.4.39736

15. Schmechel de Avila S, Iost Vinhas L. Lixo, vagabunda, piranha, puta e louca. Rev (Con)Textos Linguisticos [Internet]. 14 set 2022 [citado 3 nov 2024];16(33):154-72. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.47456/cl.v16i33.37598

16. De Souza NT, Nolascio VS, De Barros SM. “Ele não te bate, mas...” sinais sutis de relacionamento abusivo, violência e feminicídio: uma análise crítica do discurso. Obs Econ Latinoam [Internet]. 3 out 2023 [citado 3 nov 2024];21(10):15003-19. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.55905/oelv21n10-029

17. Fórum brasileiro de segurança pública [Internet]. Atlas da violência 2024; 2024 [citado 3 nov 2024]. Disponível em: https://publicacoes.forumseguranca.org.br/handle/123456789/251

18. Wacquant L. Poder simbólico e fabricação de grupos: como Bourdieu reformula a questão das classes. Novos Estud CEBRAP [Internet]. Jul 2013 [citado 3 nov 2024];(96):87-103. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/s0101-33002013000200007

19. Dos Santos Camargo CM. Memória discursiva e a análise do discurso na perspectiva pecheuxtiana e sua relação com a memória social. Saber Hum [Internet]. 11 jul 2019 [citado 4 nov 2024];9(14):167-81. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.18815/sh.2019v9n14.341

20. Caixeta JE, Barbato S. Identidade feminina: um conceito complexo. Paid (Ribeirao Preto) [Internet]. Ago 2004 [citado 4 nov 2024];14(28):211-20. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/s0103-863x2004000200010

21. Schmechel de Avila S. Ele contra ela: uma análise discursiva de testemunhos de mulheres vítimas de violência doméstica. Univ Fed Pelotas [Internet]. 2021 [citado 3 nov 2024]:109. Disponível em: https://guaiaca.ufpel.edu.br/bitstream/handle/prefix/9133/Dissertacao_Suzana%20Schmechel%20de%20Avila.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

22. Ministério dos Direitos Humanos e da Cidadania [Internet]. Violência contra mulher não é só física; conheça outros 10 tipos de abuso; 9 mar 2016 [citado 4 nov 2024]. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/mdh/pt-br/noticias-spm/noticias/violencia-contra-mulher-nao-e-so-fisica-conheca-outros-10-tipos-de-abuso

23. Ging D. Alphas, betas, and incels: theorizing the masculinities of the manosphere. Men Masculinities [Internet]. 10 maio 2017 [citado 4 nov 2024];22(4):638-57. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184x17706401

24. Rodriguez SD. Um breve ensaio sobre a masculinidade hegemônica. Divers Educ [Internet]. 20 fev 2020 [citado 4 nov 2024];7(2):278-93. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.14295/de.v7i2.9291

25. Aragão M. Os memes de humor e a naturalização da violência como caminho educativo. Interfaces Cient Educ [Internet]. 2 abr 2020 [citado 4 nov 2024];8(3):129-44. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.17564/2316-3828.2020v8n3p129-144

FINANCING

The authors did not receive financing for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Gabriela Tavares Soares, William Alves dos Santos.

Data curation: Carolina de Araújo Rezende Gonçalves, William Alves dos Santos.

Formal analysis: William Alves dos Santos.

Research: Elaine Aparecida Policarpo.

Methodology: William Alves dos Santos.

Project management: Gleice Kelly de Pádula Batista Machado.

Resources: Daniela Miotto Araújo.

Software: Bruno de Souza Prado.

Supervision: William Alves dos Santos.

Validation: William Alves dos Santos.

Display: Maiara Patrícia Vieira Nicolau Ribeiro Sanchez.

Drafting - original draft: Manuelli Aparecida Mota Rodrigues.

Writing - proofreading and editing: William Alves dos Santos.